This article was originally published by Pacific Forum CSIS on 24 May 2017.

‘This third-generation Kim already holds the titles of supreme leader, first secretary of the party, chairman of the military commission and supreme commander of the army – but he wants even more. This Kim wants recognition, vindication and authentication.’ The Observer, May 8, 2016

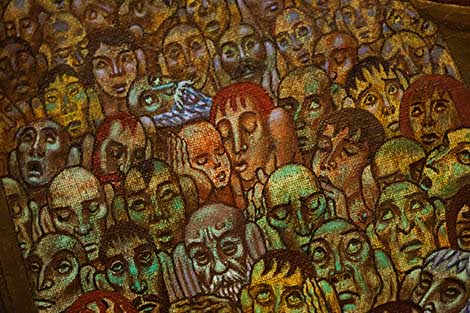

This description of Kim Jong Un is not the most lurid; in fact, it is representative of broadsheet analysis of the leadership of North Korea. It reduces analysis of the leadership of a state of 25 million people, which has an indigenous advanced scientific capability sufficient to develop nuclear weapons and advanced ballistic missile technology, to a level more appropriate to the pages of an airport pot-boiler. It trivializes analysis of a conflict that involves all the world’s great military powers, and which intermittently looks as if it might spill over into warfare that military planners from all sides assess will cost millions of lives, however and whenever the conflict ends.

The focus on Kim Jong Un as supreme leader is misplaced and dangerous. It obscures and prevents discussion of where real power lies in North Korea.