This article was originally published by the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in June 2019.

The number of armed conflicts in 2018 was slightly higher than 2017 and much higher than ten years ago, but the number of fatalities occurring in these conflicts was below average for the post–Cold War period. A key issue remains internationalized conflicts – civil wars with external parties involved – where a majority of fatalities in 2018 has been recorded.

Brief Points

- The number of state-based armed conflicts in the world increased slightly from 50 in 2017 to 52 in 2018, with the Islamic State active in 12 of them.

- There was a significant decline in conflict casualties in 2018, with 23% fewer casualties compared with 2017, and 49% fewer than 2014.

- Afghanistan is again the deadliest conflict region in the world; 48% of all casualties in state-based conflicts in 2018 were in Afghanistan.

- Internationalized conflicts and nonstate conflicts continue to represent major threats to reductions in violence.

- There were six wars in 2018, down from 10 in 2017.

A Bump or the New Normal?

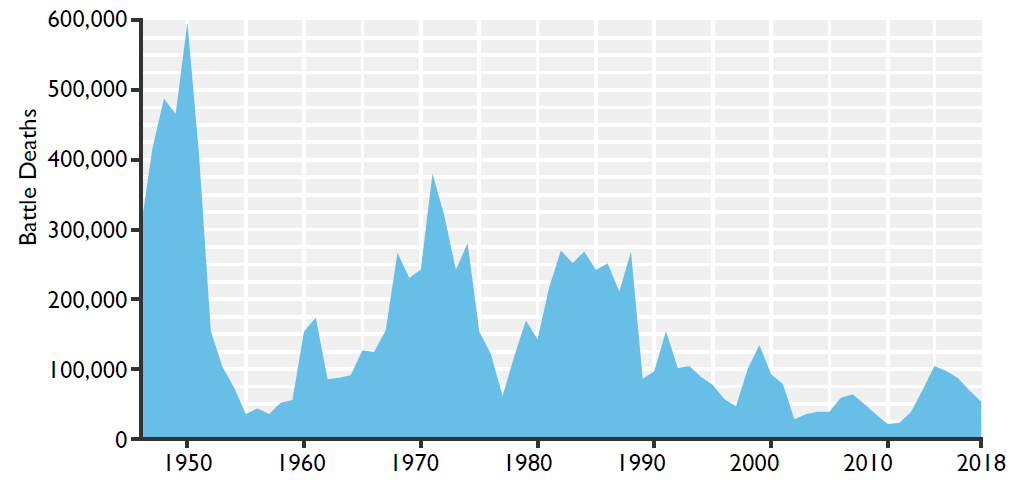

The first fifteen years of this century were exceptionally peaceful. Then in 2014, several wars became very lethal, and in particular the war in Syria. Since this time, debates have ensued about whether our current condition is the “new normal” level, or whether the recent increase should be viewed as a bump on the road to an even more peaceful world.

We are still unable to answer this question. The number of conflicts is at an all-time high, but the number of people killed in conflict is trending towards the record-low number witnessed ten years ago. The reduction in the number of fatalities is due primarily to strong reductions in deaths in Syria and Iraq, and the high number of conflicts has been the result of local Islamic State (IS) chapters spawned in new locations.

UCDP catalogues all conflict in which at least 25 people are killed in battle-related circumstances. While there are more conflicts worldwide, fewer of them cross the 1,000-fatality threshold we refer to as wars. There were 52 active conflicts in 36 different countries in 2018, compared to 50 conflicts in 33 countries in 2017. There were 10 wars in 2017, but only 6 in 2018 – a number not seen in five years. The total number of fatalities in all conflicts is down 23%, from about 69,000 to 53,000.

In short, fewer people are killed in fewer wars, but there are more low-level conflicts that potentially can spiral out of control. Hence, there is a significant danger for a negative development in the near future. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the competing trends.

Six Wars

There were six wars in 2018, in four different countries: Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and Afghanistan, which accounted for 82% of all recorded battle-related casualties. Usually groups fight to capture or significantly alter the nature of the government of a state, to gain independence for a new state, or to merge a part of a country into a different state. In both Syria and Afghanistan, two different wars are registered due to the unique nature of IS.

The political aim of IS, whether in Syria, Afghanistan, or other countries, is to establish Islamic Caliphates following Sharia doctrines. These new political entities do not respect current international borders. Such orientation makes the IS unique among rebel groups, and they appear to be at war with both governments and other rebel groups.

The two wars in Afghanistan combined accounted for 49% of all fatalities in armed conflict in 2018 and the number of people killed in Afghanistan has steadily increased over the last decade with a 30% increase from 2017 to 2018. The Afghan government and its supporters remain the main focus in the conflict, and there is little fighting between opposition groups.

Syria has a similar configuration of wars but a very different dynamic. In 2018, more than 11,000 people died in battles between the government and various insurgent groups, but at least 7,300 died as a consequence of rebel infighting, mainly involving IS, the Hawar Kilis Operations Room, and Syrian Democratic Forces. While the situation in Syria remains dire, conditions have improved significantly from the 2013–2016 period when the conflict began.

Somalia has found itself in a war between the government and Al-Shabaab ever since 2008. While 2018 was the worst year since 2012 in terms of fatalities, the fluctuations in fatalities remains rather small from year to year (between 900 and 2,700). Supported by the African Union and with military assistance from eight African countries and the USA, the Somali government has made notable progress against Al-Shabaab in recent years.

The current conflict in Yemen started when the Ansaruallah group ousted the government of President Hadi in 2014, which subsequently led to the involvement of a Saudi-led coalition in support of Hadi. While Hadi remains the internationally recognized leader of Yemen, Ansaruallah retains control of Sanaá. The Uppsala Conflict Data Program reported 4,500 battle related fatalities in Yemen in 2018, approximately 2,000 more than in 2016 and 2017, but about 2,000 fewer than 2015.

Beyond the battle-related casualties, the conflict in Yemen has fomented an adjacent humanitarian disaster with reported deaths much higher than these figures. Such numbers of indirect deaths are difficult to verify due to a sparsity of reliable data.

46 Minor Conflicts

A total of 9,360 casualties have been recorded in the 46 conflicts that did not cross the 1,000 battlerelated death threshold. Among these conflicts we find several success stories, where previously high-intensity clashes have been reduced to minor conflicts.

The war in Iraq has receded from the headlines, and, according to our definition, is no longer a war. The number of fatalities fell from close to 10,000 in 2017 to 831 in 2018. This is very good news. However, we should note, similarly low casualty levels existed in 2011–12, so we should not rule out a possible return to war in this region.

Myanmar has ranked among the most conflictridden countries in the world for decades, but the nature of conflict there is characterized by numerous, but low-intensity clashes. The signing of the 2014 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement has reduced the conflict level significantly: in 2018 fewer than 100 fatalities were recorded in the three active conflicts in Myanmar.

Colombia was listed as inactive in 2017, but became active again in 2018, as the only active conflict country in Latin America. Both ELN and FARC splinter groups were recorded with more than 25 battle-related deaths.

In 2018, Israel was involved in two active conflicts with Hamas and Iran. While neither of these conflicts recorded fatalities much above the 25 battlerelated deaths threshold, it is notable that this is the first time since 2014 that Israel has been coded as participating in an active conflict.

The Ambazonia region of Cameroon is a former British trusteeship territory, and currently the object of a secession conflict. The region was incorporated into a federation with French Cameroon in 1960. Advocates for an independent Ambazonia has remained active for decades. The political conflict turned violent in 2017 and escalated in 2018. If the escalation continues, this conflict may be classified as a war starting in 2019.

The region of West Papua in Indonesia has been intermittently contested since the Dutch withdrawal in 1965. Indonesia swiftly invaded the region and orchestrated a plebiscite supporting integration into Indonesia. The Free Papua Movement fought against this integration with the most severe period of the conflict occurring from 1976–1978 when more than 1,000 people were killed per year. This conflict has not been defined as active since 1984, but in 2018 violence re-emerged. There are scattered reports of violent events over the last decade, and last year 31 people were killed in a single event.

Internationalized Conflicts

A internal conflict is regarded as internationalized if one or more third party governments are involved with combat personnel in support of the objective of either side. UN or regional Peace Keeping Operations could count as such, depending on their mandates, but do not automatically make a conflict internationalized.

Figure 3 illustrates the two periods that stand out since the end of the Cold War. The first period, immediately after the end of the Cold War, is characterized by a large number of local conflicts that erupted in the wake of the fall of communism or were intensified by the withdrawal of support from Soviet bloc countries. At the end of the 1990s, there is a small peak, which is about the time when the war in DR Congo was at its most intense. Often labeled the most severe war since WWII, the number of people killed in battle-related situations do not support such claims.

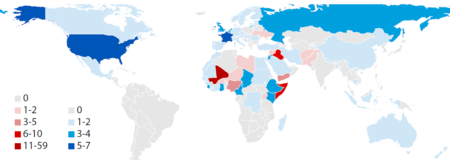

The second peak is different. Fourteen conflicts (six wars and eight minor conflicts) in 2018 were internationalized. These 14 conflicts account for more than half of all battle-related casualties in 2018, but this figure does not imply that internationalization necessarily leads to more severe conflicts.

Some conflicts do become more brutal when international actors get involved. The Vietnam War would serve as a prime example. The opposite logic is also possible, that already severe conflict attract international involvement. The rationale behind the international intervention in Libya was to prevent an escalation rather than to contribute to it. The merits of this intervention is clearly debated, but we will never know how the counterfactual would have developed.

Research indicates that internationalized conflicts are more durable and less likely to find a political solution. This durability can be due to aspects of the conflict itself, but may also be driven by the increasing number of parties involved in the conflict, which means more actors who can potentially block a deal.

The number of countries involved in internationalized conflicts has exploded over the last 15 years (Figure 4). The current peak is driven primarily by the 59 countries involved in the Mali stabilization forces. There are also several regional conflicts that have become internationalized with grave consequences as we currently see in Yemen.

Interventions are usually initiated in support of the government side in a conflict with two notable exceptions. Russia continues to support separatists in Ukraine and a Saudi-led coalition has intervened in support of the previous Hadi government in Yemen.

Looking Forward

It is quite difficult to predict what the next few years will look like. It may be safe to assume that they will resemble the current situation. 2018 was an anomaly, as the steady decline in fatalities and the record-high number of ongoing conflicts point in different directions.

Political Islam remained a dominant factor in the global conflict patterns in 2018, as has been the case for the last decade and will likely be the case for the next year. Nearly 9 out of every 10 fatalities in 2018 occur in a conflict in which at least one party has a maximalist Islamic political ambition.

Nationalist conflicts are the other significant theme among recent armed conflicts. Turkey, Cameroon, Myanmar, Ukraine, Iran, India, Somalia, Thailand, Kenya and Indonesia all have armed conflicts where independence or territorial change is the focus. Nationalism was the dominant form of conflict in the 1990s and could become so again.

In 2018, South America was the continent least affected by armed conflict. Apart from Colombia, there were no active conflicts, nor did any countries in this region send troops to other conflicts. This condition might change, however. Venezuela finds itself in an unstable position, and this crisis could result in different types of organized violence. It is possible that a civil war could erupt, which might easily become internationalized. It is also possible that neighboring countries of Venezuela would intervene on behalf of the government opposition. However, there is still hope that a peaceful, stable resolution to the current tension can be reached.

Most armed conflicts remain small, but a few escalate into wars, with long-lasting and devastating effects. The current situation, with a shrinking number of wars and a record-number of small conflicts, highlight the role of conflict management and prevention. The top priority in the years forward should be to solve or at least prevent escalation of the many minor conflicts that currently are active.

About the Authors

Håvard Strand is Associate Professor at the University of Oslo and Senior Researcher at PRIO.

Siri Aas Rustad is Senior Researcher at PRIO and leads the Conflict Trends project.

Henrik Urdal is Research Professor and Director at PRIO.

Håvard Mokleiv Nygård is Senior Researcher at PRIO.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.

2 replies on “Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946–2018”

Very good, detailed and precise article.

Congratulations,

Ricardo

Very insightful research that not doubt inform peacebuilding efforts