Assembling Future Knowledge and Integrating It into Public Policy and Governance

This article is the concluding chapter of The Politics and Science of Prevision: Governing and Probing the Future, published by Taylor & Francis Group. To read this open access book, click here.

This article is the concluding chapter of The Politics and Science of Prevision: Governing and Probing the Future, published by Taylor & Francis Group. To read this open access book, click here.

In a world of complexity, interconnectedness, uncertainty, and rapid social, economic and political transformations, policy-makers increasingly demand scientifically robust policy-advice as a form of guidance for policy-decisions. As a result, scientists in academia and beyond are expected to focus on policy-relevant research questions and contribute to the solution of complicated, oftentimes transnational, if not global policy problems. Being policy-relevant means to supply future-related, forward-looking knowledge – a task that does not come easy to a profession that traditionally focuses on the empirical study of the past and present, values the academic freedom of inquiry, and often sees its role in society as confronting and challenging power and hierarchy.

Contributing future knowledge towards the sustainable solution of complex problems can be rewarding and it is an important basis for fostering and maintaining trust between science, society, and politics. However, creating future knowledge can also be a thankless task and, worse, backfire, fuelling pessimism towards science (Pielke 2007). On top of that, future knowledge is political, because the science and the politics of anticipating and preparing for the future are closely intertwined and cannot be separated: It shapes perceptions about the future and such perceptions do not simply provide orientation between the past, the present, and the future – once future knowledge is acted upon, it influences and changes the course of the future. Conversely, institutions and governance structures influence the making of knowledge about the future, acknowledging, selecting, and legitimizing some forms of future knowledge provided by some experts and institutions, while precluding other forms (Jasanoff 2015).

This concluding chapter, building on the individual contributions to this book, highlights the complex interactions and feedback-loops between the politics and the science of the future. The two interrelated and oftentimes parallel processes of creating and assembling future knowledge and the integration of this knowledge into public policy-making and governance bring policy-makers and scientific experts from within governments, private industry, and academia in close contact with each other. While this may create friction at the intersection of science and policy, such friction can also unleash human creativity resulting in better future policies and practices while expanding the horizon of possibility. If politics and science more actively reflect differences and overlaps in their knowledge conceptions and roles in society, they will be better equipped to master the challenges of collaboration and overcome the unavoidable backlash of working at the intersection of science and politics.

Four Factors Shaping the Context of Future-Oriented Thinking Today

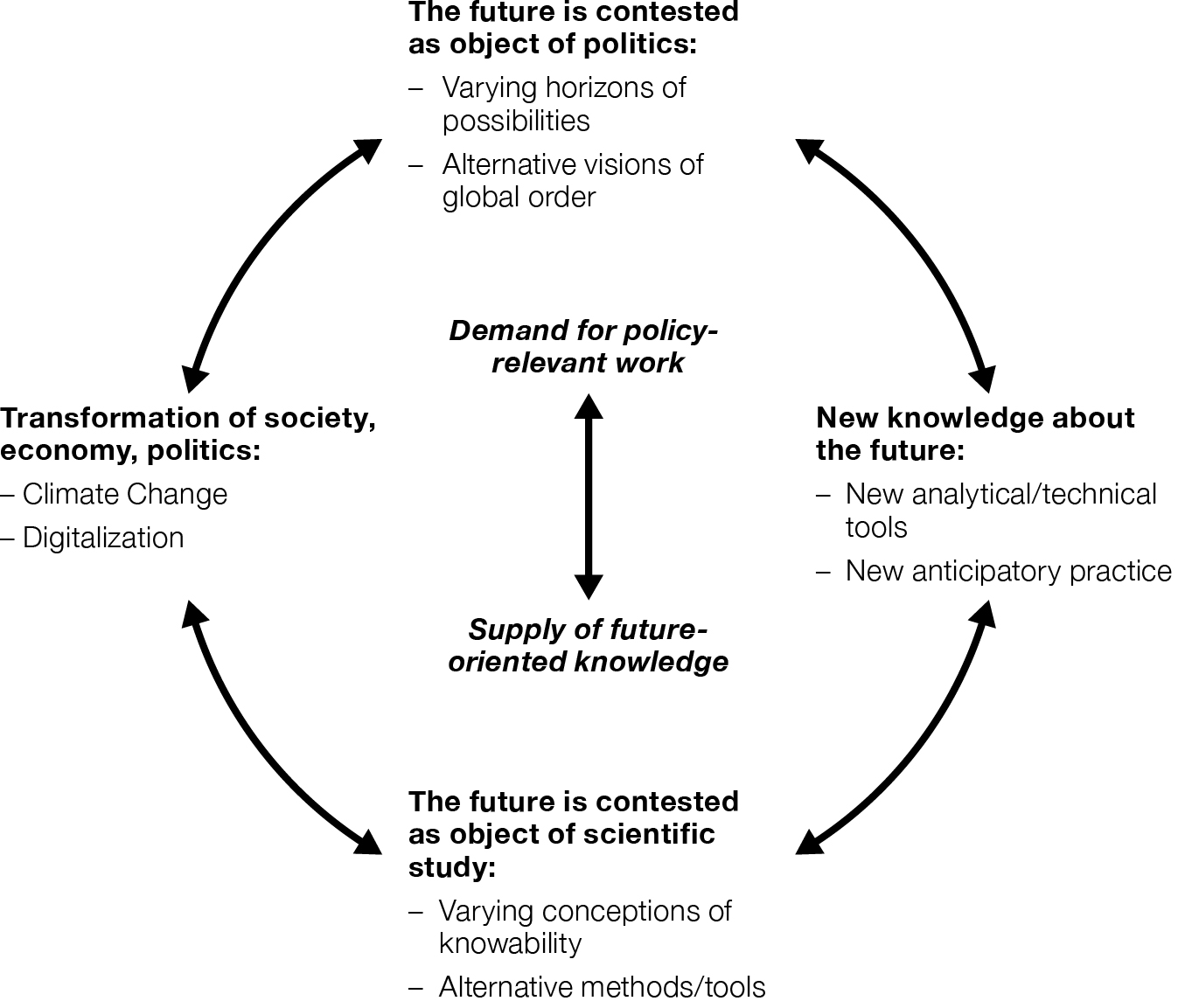

Before we discuss the intricacies and fallacies of integrating future-oriented science and politics based on the findings of the book, we would like to point out four characteristics of the current context that shape today’s environment (see Figure 14.1). The introductory chapter of this book presented the co-constitution and co-evolution of different historical imaginaries of the future and social and political orders across time from a Western point of view (Wenger et al. 2020). While the chapters of this book have focused almost exclusively on the West as well, it is in fact the emergence of alternative visions of the future in the East, especially in China, that provide a major impetus for the renewed political interest in the future. Competing and sometimes clashing visions of the future need to be increasingly negotiated at the global level and integrated not just into national policy but into global governance systems (Simandan 2018). This situates the future as a contested object of politics firmly on international relations and security studies territory.

The past decade in global politics is characterized by discussions about the consequences of a changing power distribution between the West and the East with many open questions about future order remaining (Maull 2018). Not least because of the lingering effects of the financial crisis of 2008, policy-makers in the Western world tend to fall back onto a discourse that paints the world as complex, uncertain, and unpredictable, full of risks that cannot easily be controlled and major ruptures that are inevitable (and often unforeseeable). At the same time and as an extreme counterweight, China’s state-driven modernization project came to be seen as an alternative development model to the world (Breslin 2011; Zhao 2010; Zeng 2019). The launching of the ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative in 2013 (now just Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) – a gigantic infrastructure project connecting China with Europe through a series of continental and one maritime corridors – marked a major turning point in Beijing’s geo-economic strategy (Ferdinand 2016; Jones and Zeng 2019).

The shifts in global economics and politics are in line with asynchronous shifts in the temporal thinking in Western and in Chinese politics. While for Western policy-makers the horizon of possibilities seems to be shrinking, for Chinese policy-makers it seems to be expanding. In the West the future is debated in a context of political fragmentation and rising populism. In China the future is associated with a revival of historical greatness after a century of humiliation (Westad 2020; Zheng 2012). Neither Western nor Chinese policy-makers perceive the future through the temporal regime of Francis Fukuyama’s presumed ‘end of history’ any longer (Fukuyama 1992). On the contrary, their different visions of the future reflect competing and alternative visions of regional and global order. In a world in which the liberal order is clearly no longer universally acknowledged and the rule-based capacity to act at the international level seems limited, the future as an object of (international) politics cannot but be contested.

Not least because of the ‘failure’ to anticipate and predict key global events, the future is a contested object of study in the social sciences and beyond as well (Assmann 2013; Hölscher 2017; Jasanoff and Kim 2015). The past decade witnessed a growing debate about the epistemological challenges of making claims about the future. Like in politics, this debate evolves as science and academia more broadly are changing as well (Nowotny et al. 2001; Schimank 2012). On the one hand, the international scientific system has expanded greatly over the past decade, with different social and political contexts leaving more or less room for academic freedom. Moreover, scientific knowledge is not only – and in some fields like artificial intelligence no longer primarily – produced in universities that are characterized by a disciplinary and autonomous organization of knowledge production, but increasingly by more diverse actors from different sectors of society that represent a more transdisciplinary, applied, and reflexive organization of science (Gibbons et al. 1994; Dusdal 2017).

Next to these changes in politics and science, we see two meta-processes that not only affect all societies and political systems in one way or another but are also influencing the public demand for policy-relevant work in general and scientific supply of future-oriented knowledge in particular. The first is climate change and related issues. It expands the temporal horizon of contemporary policy-making by increasing the time span between cause and harmful effect considerably and thereby accentuates distributional conflict at the global level and across generations. The future thus becomes a mere extension of the present, as scholars like Sheila Jasanoff and Helga Nowotny point out. Together with other global challenges like financial instability, emerging diseases, or internationalized civil wars – that all have transnational regional and global economic, social, and political consequences – climate change stands for a big, global challenge that no single political actor can deal with on its own. Second, transformative new technologies, especially in the field of artificial intelligence, promise huge potential benefits for the digitalized society of the future but at the same time create room for new, and potentially huge risks (Fischer and Wenger 2019). These technologies whose development is dominated by large global technology companies and some universities stand for potentially sweeping transformations across sectors and societies beyond the control of the state.

Last, these technological, social, and political changes are influencing and are influenced by new tools of future knowledge creation. First, the rapid increase in computing power, the vast growth in data, and the optimization of analytical algorithms have greatly expanded the range of present and future application of AI technologies. On the one hand, these new technologies come with the promise of controlling and managing the future on an unprecedented scale and speed, although the temporal trajectory of the development from narrow to more general forms of AI is highly uncertain. On the other hand, these new technologies, while heavily contributing to the rising scientific interest in the future, create major uncertainties as regards their technological implications (safety, transparency), their social implications (biased decision-making), and their political implications (totalitarian surveillance) (Dafoe 2018).

At the same time, the social and political changes discussed above are also affecting and are affected by new anticipatory policies and practices. First, the export of the precautionary principle from the field of environmental politics to other policy fields, and the stellar ascendancy of the concept of resilience across many fields of public policy and global governance reflect that policy-makers are aware of the limits of future knowledge. In a world of risk and uncertainty, policy-makers – reclaiming sovereign decision-making from experts – prepare for non-linear developments, focusing on how best to rebound in unavoidable crises and learn in a decentralized mode (Aradau and van Munster 2007; Ewald 2002). Second, in the context of a transdisciplinary perspective, new forms of science–policy dialogues are emerging that represent a more reflexive and deliberative organization of future knowledge. Such anticipatory practices integrate public expectations as early as in the definition phase of research problems, map different policy measures and options and explore their political and ethical impact together with public, private, and civilian stakeholders (e.g. Chilvers 2013; Edenhofer and Kowarsch 2015).

After laying out the current context in thinking about the future from a Western perspective, this concluding chapter proceeds as follows to summarize the findings of this book: A first section highlights how different knowledge conceptions and temporal logics of and within politics and science complicate the process of creating and assembling future knowledge. It then explores how a better understanding for the interlinkages between method, practice, context, and political purpose of different types of future reasoning can facilitate the collaboration between policy-makers and scientists. A second section highlights what emerges from the empirical chapters in this volume. It discusses how risks and uncertainty are dealt with across different policy-fields, from climate, health, and financial markets to biological and nuclear weapons proliferation, civil war, and crime. We compare whose predictions and forecasts are integrated how deeply into what forms of governance systems and what consequences this has for politics, society, and science.

Creating and Assembling Future Knowledge at The Intersection of Science and Politics

Future knowledge is created and assembled at the intersection of science and politics. This process brings two systems in close contact with each other that ideally fulfil different roles in society (‘deciding’ vs. ‘learning’) (Maasen and Weingart 2005). As a consequence, the knowledge produced in academia is not automatically the same as that required in politics. In fact, science and politics are not only guided by different knowledge conceptions, they also differ in the temporal logic of thinking and acting. Keeping this in mind helps to dissolve the paradox of a growing demand for policy-relevant scientific knowledge amidst widespread disenchantment about academia in policy circles; but also of academia’s growing willingness to contribute to the solution of big social problems amongst the disposition of many scientists to keep a critical distance from politics and the structures of power policy-makers represent.

Politics is primarily geared towards deciding and its temporal orientation is toward the future. Knowledge in politics is used strategically to solve public conflicts, through deliberation and compromise in democratic politics or through directives and hierarchy in more authoritarian and technocratic politics. Science, by contrast, is primarily geared towards learning and its temporal orientation is towards the present and the past. Knowledge in science is systematically developed through the scientific process, i.e. through the systematic collection of empirical data to investigate and/or explain a phenomenon and through the peer review of research results (Maasen and Weingart 2005; Adam 2010). Scientific from the normative or moral question of how this knowledge should be used or not used by society. The traditional disposition of basic research in universities is to stay away from politics which is (quite rightly) associated with the strategic use of knowledge.

Yet politics is not just about the closure of political conflict, as science is not just about systematically questioning existing knowledge. Future knowledge in politics is also used to create a sense of belonging, linking it to the past and the present for orientation; and it is also a site through which human creativity and agency manifests itself in order to solve concrete societal problems. Scientific knowledge left the confines of universities long ago through the successful transfer of research methods, results, and young academics into other sectors of society – including public administration, industry, and civil society organization – thereby fostering competing centres of knowledge production. As a consequence, the process of creating and assembling future knowledge is increasingly organized in a transdisciplinary mode that emphasizes the dynamic interchange between basic and applied research and the flexible collaboration between producers and users of future knowledge in the context of specific practical applications (Nowotny et al. 2001).

The often deplored gap between academia and politics reflects the traditional separation and autonomy of politics and science. However, such a view does not adequately reflect the many nodes of continuous interaction between the two spheres and the many different transmission processes through which future knowledge travels across the boundaries of the two subsystems. Both the STS perspective and the pragmatist perspective introduced in this book reject the strict science/policy, internal/external dichotomies of more traditional views (Jacob and Hellström 2000). Jasanoff in Chapter 2 discusses how from a STS-perspective future knowledge is co-constituted by epistemic, institutional, and social forces. Science influences society, but is itself affected by social factors. Imagining and preforming the future are thus highly political endeavours (Jasanoff 2020). In Chapter 3 Gunther Hellmann adds a pragmatist perspective that conceptualizes both policy-makers and scientists as pragmatist problem-solvers that apply ‘know-how’ to solve social problems in order to cope. According to this view, future knowledge as ‘know-how’ is acknowledged in social interaction and through language (Hellmann 2020).

The Future Is Contested in Science and Politics

The knowledge conceptions and temporal orientation differ not only between politics and science – the future is inherently contested within these two subsystems of society as well. There is debate and dispute within science and politics about both the epistemology as well as the political and ethical implications of prevision. These different perspectives on and knowledge claims about the future interact in both the processes of creating and assembling future knowledge as well as the processes of integrating future knowledge in public policy and broader (global) governance systems.

Different scientific disciplines have different epistemological perspectives on the future and these perspectives translate into a great diversity of disciplinary tools and practices of dealing with the future and its uncertainties (Li et al. 2012). From the perspective of the natural sciences and engineering, the future needs to be discovered and invented through the creation of new knowledge. From the perspective of positivist social sciences, the future can to some extent be predicted, based on empirical cause–effect explanations. From the perspective of history, sociology, and post-positivism in IR and beyond, the future can be imagined and its possibilities can be explored, based on an understanding of how the past, present, and future are interlinked and based on critical normative knowledge, as Francis J. Gavin discusses in Chapter 5 (Gavin 2020). Only rarely is it obvious to policy-makers which epistemological perspective shapes the future knowledge they seek to act upon, or which type of ‘know-how’ informs their policy decision. It is such an awareness, says Michael Horowitz, that policy-makers and academics need to foster together so that it is possible to fine-tune expectations about the results of different forecasting activities (Horowitz 2020).

Indeed, different disciplines offer different tools and methods to deal with the uncertainties of the future. The truth claims of these different approaches reflect different conceptions of ‘knowability’ in relation to the future. The truth claims of theory-guided, backward-oriented positivist predictions are based on data and calculation. The historian’s truth claims are based on a narrative that is sensitive to specific events and structural causes which appreciates that history evolves in a non-linear mode. From a pragmatist perspective, the truth claims are based on social acknowledgement and acceptance; a view that is shared by many STS scholars who in addition highlight the transmission of predictive knowledge across empirical and actor–agency boundaries. Furthermore, different tools of future knowledge production and methods of anticipating the future exhibit a different time horizon as regards the cause and outcome of what is anticipated or predicted.

In politics, different visions of an alternative future are continuously negotiated. Policy-makers intuitively approach the process of imagining the future as a deeply political endeavour that is constitutive for decision-making in the present. Decisions about the future precipitate a specific trajectory, while always precluding alternative futures. Thus, imagining the future and acting upon visions of the future are closely linked to questions of power and democracy. The politics of the future offer opportunities in the present for redistributing power and influence and for promoting alternative policies that align with different values and interests (Mische 2009). The competition between alternative futures at the level of international politics may have far-reaching consequences for the on-going transformation of the global and regional order. The negotiation of alternative futures, at the level of domestic politics, is closely linked to the question of who – among policy-makers, experts, or scientists – has how much and what type of influence in a given institutional setting, from democratic to more authoritarian regimes (Jasanoff 2020).

Policy-makers usually have a good understanding of the limits of future knowledge and the fact that the ultimate responsibility for decision-making cannot be delegated. They know quite well that they more often than not need to decide in a world of risk and uncertainty. On the one hand, policy-makers may also be tempted to manage the risks to their own reputation rather than the primary problem that cannot really be controlled, as Myriam Dunn Cavelty notes in Chapter 6 (Dunn Cavelty 2020). On the other hand, they may stabilize future expectations in the face of uncertainty through social conventions and institutions, as noted by Peter J. Katzenstein and Stephen C. Nelson in Chapter 9 (Katzenstein and Nelson 2020). One example are precautionary policies that allow politics and society to take action even if the cause–effect relationship behind a problem is scientifically not well understood (McLean et al. 2009). What emerges from the empirical chapters in this volume is that the move toward precautionary politics can be observed at both ends of the predicted time horizons – the very short one in the context of proactively governing the prevention of crises in the global financial and health systems; and the very long one in the context of climate-adaption policies.

Fitting Method and Anticipatory Practice to Context and Political Purpose

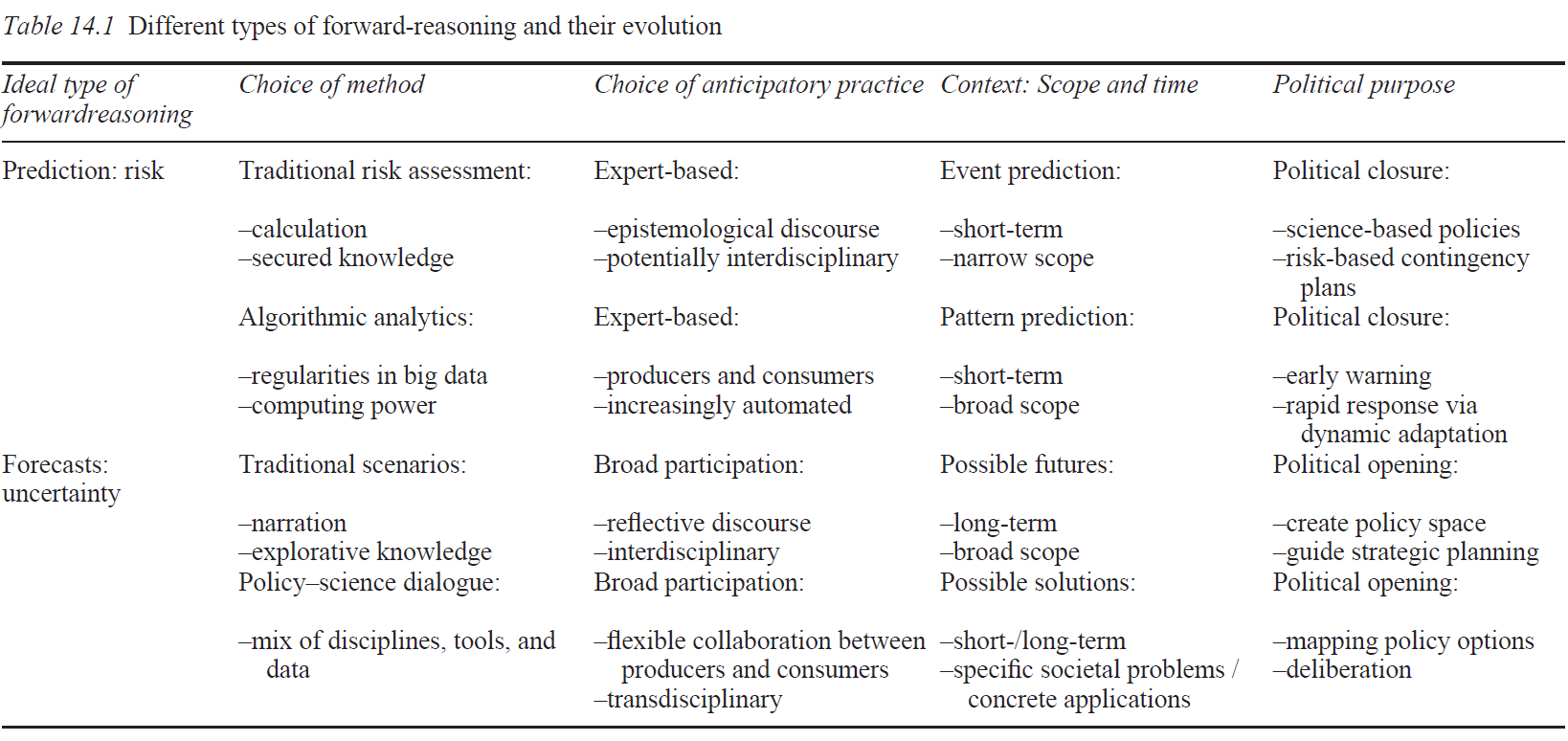

The field of future studies is exhibiting a plethora of methods and modes of anticipatory knowledge-generation. The future oriented-work in academia is highly diverse and characterized by a multitude of different disciplinary tools and practices (Bell 1964). Yet too often – and not only in politics – the different analytical perspectives and epistemological assumptions remain hidden and unexplored. This is of little help for politics and science, particularly for the alignment of mutual expectations with regards to the who, what, when, where, why, and how of creating and assembling future knowledge. In fact, the choice of method which reflects assumptions about the ‘knowability’ of the future (i.e. levels of scientific uncertainty) and the choice of anticipatory practice that reflects assumptions about the necessary degree of acceptable participation

(i.e. levels of normative and political contestation) must fit the object (narrow/ broad scope) and the political purpose (political closure/political opening) of prevision.

In Chapter 6 Dunn Cavelty introduces two ideal-types of forward-reasoning that are labelled prediction and forecast that can serve as a basis for developing a typology for future use (Dunn Cavelty 2020). Prediction comes in the form of traditional risk assessment, a method that relies on statistics and secured knowledge (past data) to calculate the probabilities of an event. As an anticipatory practice, prediction is mostly expert-based and focuses on an epistemological (potentially interdisciplinary) discourse. The assessed cause and outcome generally reflect a narrow scope and a short time horizon. The political purpose of Prediction is to facilitate political closure that allows to compromise on new science-based policies or on risk-based contingency plans. Forecasts, by contrast, come into play when uncertainty is foregrounded in decision-making. Forecasts come in the form of scenarios which represent a method that sketches possible futures in a narrative way. As anticipatory practice, forecasts are geared towards broad participation and focus on a reflective discourse among an interdisciplinary group that represents diverse backgrounds. The explored possible and more or less plausible futures generally reflect a broad scope and a long time horizon. The political purpose of forecasts is to explore different plausible futures and create a policy space for long-term strategic planning.

Both ideal-types of forward-reasoning are currently evolving, as new methods and new anticipatory practices are increasingly becoming available and acceptable, reflecting the broader technological and social trends discussed in the introductory section of this concluding chapter (see Figure 14.1). First, prediction comes increasingly in the form of algorithmic analytics and data-science that relies on growing computing power to establish regularities in huge amounts of data. As an anticipatory practice it is expert-based, at times bringing together the producers and consumers of prediction, and increasingly automated. The assessed causes and outcomes are not always well understood, but the short-term predictive power of such regularities has a potentially broad scope of application. The political purpose of predictive pattern recognition is often early warning and rapid response through dynamic policy adaption – which may change the ‘why’ and ‘for whom’ of prediction in an increasingly automated way (Buchanan and Miller 2017).

Second, forecasts increasingly come in the form of more open-ended science–policy dialogues, in which what constitutes a socially relevant research question is already discussed in a participatory way. As an anticipatory practice it is transdisciplinary in nature and emphasizes the dynamic interaction between basic and applied research and the flexible collaboration between multiple producers and users of knowledge. The assessed causes and outcomes are purposefully mapped for a broad set of policy options over the short-, medium-, and long-term. The political purpose of such dialogues is to map the dynamic interaction of technology, markets, and politics and explore different policy measures and options for a specific societal problem together with public, private, and civil stakeholders, thereby providing ‘intellectual space’ for a deliberative political process about possible futures (Edenhofer and Kowarsch 2015; Grunwald 2014).

Outlining these two ideal-types of forward-reasoning highlights that the choice of method and practice in anticipating the future needs to be made by politics together with science, because the method and practice of creating and assembling future knowledge must fit the object and political purpose of prevision. Over time, we can observe a shift from anticipatory practices that were limited to a one-directional dissemination of scientific knowledge from science to politics to more dialogical practices between policy-makers and scientists – reflecting the growing complexity and interconnectedness of policy problems, on the one hand, and the changing relationship between science, society, and politics, on the other (Akin and Scheufele 2017; Doubleday 2008). In a world of risk and uncertainty, the key task for policy-makers and scientists in anticipating the future is often to optimally integrate ‘analytic and deliberative processes’, combining scientific expertise with value orientation (Klinke and Renn 2002).

Moreover, a common understanding of the opportunities and limits of different anticipatory methods helps to see them as mutually supportive rather than mutually exclusive. Risk management approaches and forecasting processes come together in crises decision-making processes when ruptures and continuities meet. The two types of future knowledge need to be combined in order to successfully manage major catastrophes. While predictive knowledge is used to stabilize fluid situations via standard operational procedures (and to automatically adapt such procedures to rapid changes in the environment), knowledge from forecasts can provide orientation when it seems appropriate to break rules and conceptualize crises as an opportunity for learning, (policy) change, and self-reflection (Snowden 2015). Crises situations give rise to a fundamentally normative question: How can ‘socially robust knowledge’ (Nowotny et al. 2001: 166) be produced and applied in order to solve societally salient problems and to achieve societal ‘“betterment”, reconstruction and emancipation’ (Bauer and Brighi 2009: 2).

Click on image to expand

Common Goals and Critical Challenges

Politics and science in a democracy have a strong common interest in a transparent and open process of creating and assembling future knowledge. Knowledge and education are a precondition for broad-based participation and deliberation in democratic processes, especially under conditions of uncertainty and ambiguity (Dewey 1954). ‘Fake news’ and growing pessimism towards technology, experts, and scientists are undermining social trust and discursive politics. Against this background, politics and academia depend on each other: While the key contribution of scientists in academia is to provide peer-reviewed and transparent (future) knowledge in terms of epistemological premises, methods, and data, the key contribution of policy-makers is to design a deliberative and forward-looking political process that is anchored in democratic participation.

The key challenges for science and academia are twofold: First, scientists in universities must become more flexible and accustomed to work in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary settings, of course without losing their disciplinary anchoring. Future knowledge is inherently multidisciplinary and combines basic and applied research output in support of policy solutions to complex and increasingly interconnected and international societal challenges. Scientists are expected to be transparent about their epistemological perspectives, methodological choices, and the limits of knowledge they produce. Second, academia should more actively reflect its influence in society – and how social factors influence the development of universities. Scientists have a choice as to when and how they want to engage with politics and what role they want to play in society (Pielke 2007). Protecting their reputation and the peer-review system that insists on intersubjectively verified knowledge (re)discovery is a legitimate goal, as is to leave the application of new predictive tools to others. Yet academia should insist that it is not marginalized in society as non-academic knowledge providers expand their role.

The key challenges for politics are also twofold: First, politics must come up with a more coherent and transparent policy and process for assembling and integrating future knowledge in public policy and governance. This includes clearly assigned roles and responsibilities within bureaucracies for early warning and horizon scanning, strategic analysis and policy planning, and data protection and management, on the one hand, and the definition of transparent mechanisms for multi-stakeholder involvement in future-related governmental activities, on the other. Second, politics should more actively reflect on the strength and weaknesses of different anticipatory methods and practices and on the ethical and political implications of future knowledge, including what the origin (i.e. industry, university, civil society) of future knowledge means for the dependence of the public sector on these actors in the fulfilment of critical state functions. Protecting its ability to cope with critical challenges under uncertainty and great time pressure is a legitimate goal. Yet politics needs to acknowledge that preparing to efficiently and effectively collaborate across different levels of national and international politics and across society, industry, and politics has become the key for dealing with complex day-to-day problems as well as future crises and catastrophes.

Integrating Future Knowledge into Public Policy and Governance and Its Consequence for Science, Society, and Politics

The empirical chapters in this book discuss and analyse how future knowledge is integrated into decision-making. This is when questions of power and democracy are coming to the fore. The politics of the future offers opportunities to (re)negotiate different future visions through a process of social interaction. Future knowledge is not just a tool of policy-making. Once it is integrated in a specific vision of the future and acknowledged – precluding alternative futures – it co-constitutes and precipitates a specific future trajectory. The integration of future knowledge into public decision-making has (sometimes far-reaching) consequences for politics, society, and science and the empirical chapters of the book assess these consequences across different policy fields – from climate, health, and markets to bioweapons, nuclear weapons, civil war, and crime.

Rather than discussing how risks and uncertainty are dealt with in the individual policy fields, we will concentrate on two questions, highlighting and comparing what emerges from the chapters in a comparative perspective. It matters greatly from a political point of view whose predictions are integrated how deeply into what forms of governance systems. Future knowledge may have been created, supplied, and combined by academia, industry, public bureaucracies or a diverse group of scientists and experts from different backgrounds. This knowledge may be integrated at the national and/or international level of policy-making and inform single-actor or multi-level and multi-stakeholder decision-making processes. The ‘who’ and ‘how’ of integrating future knowledge in public policy and (global) governance is addressed in the first subsection below.

The second subsection concentrates on the consequence of decision-making for politics, society, and science. Some of these consequences may crystallize at the global level and reflect competing visions of global order, while other consequences may become visible at the national and sub-national level, within bureaucracies or some other section of society. A recurring theme in a globalized world is that global systems and markets demand global solutions, yet most politics is local and global governance is still weak. Already aligning local, regional, and national interests within states and societies is difficult. Negotiating competing visions of regional and global order at the international level is even more daunting, especially in a period in which alternative future visions among great powers emerge and the associated shifts in temporal thinking in East and West move into opposite directions.

The ‘Who’ and ‘How’ of Integrating Future Knowledge in Public Policy and Governance

In the following, we proceed in three steps according to the main actor of the prediction. First, we discuss the integration and non-integration of academic predictions in policy-making; second, we highlight the growing role of private actors in prediction and discuss the different modes of integrating private predictions into varying governance systems; and third, we highlight the intricacies of integrating predictive knowledge created by public actors at the national and international levels.

The two chapters on prediction by academia represent two extreme cases in a continuum of fully to not-at-all integrated into policy-making. Whereas the predictions by climate scientists are widely integrated at all level of climate adaptions policy-making, the predictions by conflict researchers so far lack policy relevance and are not directly integrated into policy-making. The now decade-long, deeply politicized row over the contributions and recommendations made by climate scientists is clearly the most visible example of a new form of science–policy interaction (Edwards 2010). Maria Carmen Lemos and Nicole Klenk in Chapter 7 analyse the complexities of climate adaptiondecision-making across different levels of government and in a multi-stakeholder setting (Lemos and Klenk 2020). They show how the knowledge that underpins the decision-making is co-produced by science and policy, at times paralyzing politics while politicizing science. Scientists are challenged to predict climate change at the local level – where the uncertainties are bigger than in their global models. These scientific uncertainties, Lemos and Klenk conclude, complicate decision-making, as policy-makers grapple with complex policy trade-offs between climate-adaption and other socio-economic and political interests.

Academics working in the subfield of conflict research dedicated to the prediction of civil wars and political violence, by contrast, stay aloof from engaging politics and society, as Corinne Bara shows in Chapter 11 (Bara 2020). They focus on the development of cutting-edge scientific methods to explore and test the limits of prediction on a rare and hard target – the outbreak of civil war. The field shares a positivist paradigm of research that integrates mathematical models and sophisticated computational techniques. The predictive conflict researchers insist that there is a fundamental distinction between explanation and prediction. From an analytical point of view, this makes sense since risk factors identified in past conflict may fail to predict in unseen new data. Consequently, out-of-sample model validation is at the heart of the standard procedure they develop. In principle, their work is relevant for government and society precisely because of its focus on methodological expertise and the fact that all their predictions, tools, and data are made transparent and verifiable by peers. Yet so far the work has received only little attention in policy circles, lacking direct policy relevance.

One of the key trends observable in the empirical chapters is the growing role of private actors in the production of predictive knowledge. In the context of growing concern about a newly emerging bio-weapons threat and almost no publicly accessible knowledge about potential capabilities and motivations of state competitors, public actors like the Pentagon and NATO are increasingly turning to science fiction in thinking about the potential political and military impact of transformative technologies in the life sciences. Novels and films, as Chapter 10 by Filippa Lentzos, Jean-Baptiste Gouyon, and Brian Balmer demonstrates (Lentzos et al. 2020), can act as a particularly accessible source of imagination, because they emphasize the human rather than the technological dimension of emerging threats and focus on possible non-linear dynamics. In highly indeterminate contexts with little available data, science fiction may be added as an additional element to the wider process of anticipatory knowledge creation by key public actors.

The central role of fiction for decisions made under uncertainty is confirmed by Katzenstein and Nelson in their analysis of financial market governance failure in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis (Chapter 9). Prior to the crisis, private rating agencies played a key role in the promise of self-regulating global financial markets. Market participants and policy-makers assumed that the new securitization technologies provided by rating agencies would domesticate uncertainty into manageable risk and make government regulation largely obsolete. Although the crisis proved the agencies to be spectacularly wrong, they kept their central role. The near melt-down of financial markets, Katzenstein and Nelson point out, reminded market participants and policy-makers that financial markets are ambiguous, characterized by risk and uncertainty, and that in the face of epistemic uncertainty they would need to rely on social conventions and institutions to stabilize markets. Thus, central bankers not only calculate risk, but also influence expectations and practices of market players exercising social power. Financial market dynamics are in reality deeply intertwined with social conventions and institutions (Katzenstein and Nelson 2020).

Private actors and their predictive tools play an increasing role in the day-today management of many other complex social problems. As Matthias Leese shows in Chapter 13, the growing computing power and the algorithmic exploitation of ever bigger data-pools have the potential to fundamentally transform the relationship between the police and the future. Yet there is a certain mismatch between the promises of the industry that develops and provides the software, and the practices of the police forces that use the software to collect and analyse crime data and organize their work accordingly. Whereas the industry promises near-repeat modelling that would allow to catch a criminal before the crime, institutional structures, organizational routines, and limited financial and personal resources severely limit the practical flexibility of situational planning and operational adjustment. Predictive policing, Leese argues, should not just be seen as a technological tool, but rather as a socio-technical assemblage through which societies address the future in the everyday production of security (Leese 2020).

Public actors using their intelligence agencies produce their own predictive knowledge both at the national level and at the intergovernmental level and within international organizations like the WHO. In Chapter 12 Jonas Schneider discusses the case of the US government that mandated its intelligence agencies during the Cold War with the impossible task of assessing and predicting the global spread of nuclear weapons. The US agencies tended to overestimate nuclear proliferation and, according to Schneider, this reflected the way they dealt with uncertainty. Lacking information about potential proliferators’ intent and more generally about domestic and international demand-side factors, they placed too much emphasis on overall supply-trends and a given state’s technical capability to build the bomb. Moreover, the fact that both the producer and the consumer of the future knowledge were part of the same governmental bureaucracy did not eliminate the tension between the two. Decision-makers wanted unequivocal claims, Schneider reminds us, while analysts, well aware of the perils of predicting state behaviour under huge uncertainty, generally preferred qualifying language – confirming an enduring tension between policy-makers and their intelligence services (Schneider 2020; also Jervis 2010).

Unprecedented progress in digital health technologies and artificial intelligence in combination with the accumulation of massive amounts of health-related data have driven what Ulla Jasper in Chapter 8 calls a policy paradigm of ‘anticipative medicalization’. Coming together in the WHO, member states decided to establish an all-risk surveillance system for the real-time detection of emerging disease events that committed all members to install a state-wide monitoring system in order to collect national data that would – after aggregation and analysis at the WHO – be integrated into WHO regulation and global health policy-making. Jasper narrates how the current precautionary governance system of global health risks was co-constituted by these new technologies and social, economic, and political interests of actors that pushed for stronger and broader global communicable disease control. Yet she cautions that despite the current widespread technological optimism many fundamental ethical and politico-regulatory questions remain unresolved.

The Consequences for Politics, Society, and Science

After establishing the wide variance in the ‘who’ and ‘how’ of integrating future knowledge in public policy and (global) governance we will discuss some of the consequences of decision-making in a world of risk and uncertainty for politics, society, and science. Once again we will proceed in three steps, highlighting first that predictions indeed do have major political consequences and at least to some degree do co-create the future, sometimes in unintended ways; second that they do affect and change power structures in society as well as in politics, raising new complex ethical and political issues; and third that we can observe some of the complex feedback loops between politics and science outlined in the preceding sections.

Predictions, once integrated into decision-making and acted upon, can have a major impact on national and international policy and practice. Moreover, the intensities of the impacts are not necessarily directly correlated with the accuracies or inaccuracies of the predictions. Only the future will tell how accurate they were and in the meantime they may change the future to some degree regardless of their accuracy. Probably the best example of the great consequences predictions can have for a country’s foreign policy and for the evolution of the global order is the case of the US intelligence services’ regular assessment of what the global nuclear landscape would look like in five to ten years. As Jonas Schneider shows in Chapter 12, the pessimistic and alarmist forecasts played a crucial role in legitimizing a shift in US policy from nuclear sharing to nuclear nonproliferation (Schneider 2020); a shift that turned out to be crucial for establishing and strengthening the global nonproliferation regime, decisively shaping the future global nuclear order (Wenger and Horovitz 2018). Paradoxically, the biggest shifts in US policy occurred at the very time when the intelligence estimates were the least alarmist and some even under-predicted nuclear proliferation. Policy-makers simply disregarded the non-alarmist estimates, using the older alarmism to legitimize the new policy.

In their analysis of climate adaptation-decision-making, Lemos and Klenk show how the integration of scientific uncertainty in multi-level governance systems can complicate decision-making and at times can lead to political blockade (Chapter 7: Lemos and Klenk 2020). They present a case from the US heartland, in which the local level successfully mobilized adaption capacities and developed credible adaption plans. Since these local initiatives were, however, not well-aligned with policy-making at the regional and national levels, local actors received only little financial support and the good plans remained a paper tiger. Another case highlights how vulnerability assessments can have unintended consequences. The vulnerability maps were co-produced by multiple stakeholders, but once they were ready for publication the question arose who would be liable for the likely changes in property values following their official release. Predictive uncertainty in vulnerability maps can translate into legal uncertainty as regards the question of who is responsible for the production of risky knowledge. A third case – already leading over into the implication of prediction for democratic politics – underlines how the inclusion of scientific prediction in decision-making can facilitate a technocratic kind of policy-making. The inclusion of climate models in local climate adaptation policy-making increased the role of technocrats that gained a disproportionate influence over distributional outcomes.

The integration of future knowledge into public policy and governance offers opportunities for redistributing political power and social influence at the national and international level, posing new ethical and political dilemmas. The establishment of a global health surveillance system in effect prioritized disease control over other global health policy goals, Ursula Jasper argues in Chapter 8 (Jasper 2020). With its emphasis on early warning, quick response, preparedness and resilience, the global health governance system reflected the precautionary policy approach of the industrialized states, while the key interest of the developing countries – like access to universal healthcare and pharmaceutical products – were marginalized. The shift from a curative and remedial approach to individual health to a new approach that emphasizes predictive genetic diagnostics and individual prevention also poses new ethical and socio-political dilemmas. The predictive euphoria, Jasper notes, may create a slippery slope that can lead to uninsurable individuals, genetic discrimination, and eugenic selection.

The growing role of private actors in prediction is another trend that has the potential to affect politics and society in major ways. Analysing the case of predictive policing, Leese demonstrates in Chapter 13 that, on the one hand, society and cultural values shape how the predictive software is used. While commercial software providers and police departments in the US use the new technical tools for individualized crime prediction that focuses on a potential offender’s risk profile, most European providers and police forces implement predictive policing tools that foreground the place and time of future criminal activity. On the other hand, however, the integration of algorithmic software developed in industry may increase the dependence of public actors on the private sectors in the fulfilment of critical state functions in the area of security and safety. Moreover, the integration of proprietary software in the day-to-day operations of governmental agencies raises the question of how public actors can ensure that they know what the software does and independently evaluate its transparency, fairness, and security (Leese 2020).

Finally, the interaction between science and politics can work through complex feedback loops that affect science and society in unexpected ways. Two examples emerge from the empirical chapters of this book. First, Katzenstein and Nelson show how the models of economists not only analyse markets, but alter them. The rationalist ideas of economists are assimilated by market participants and policy-makers and – against better knowledge – integrated in both governmental regulations and the operation of the financial system. Thus, unwillingly, economists participate in a social performance out of which emerges a fictional future world. Economists, Katzenstein and Nelson conclude, should put the social back into the science that analyses financial markets (Katzenstein and Nelson 2020).

Second, while the interaction between climate science and climate policy provides object lessons about backlash and the risk of politicization of science, staying aloof of society and politics, as in the case of predictive conflict researchers, comes with costs as well. Both science and politics miss out on an opportunity to jointly contribute to better anticipation and early warning of at least some short-term violent outcomes. For instance, academics could more systematically explore policy-relevant predictions on specific risk factors that could be changed by policy or model and evaluate alternative policy interventions that would allow public actors to choose more systematically between different policy measures. Yet as long as there is only limited interaction with the policy world, public policy will rely on predictions provided by political risk analysis firms, NGO’s or governmental units. In most of these cases, data is confidential and the methods of prediction are not made transparent. Conversely, the research field has not reflected on how academic civil war prediction can and should influence policy-making and what consequences this may have for politics, society, and science.

Conclusion

The politics and science of the future evolve together and every new era comes with its specific promises and pitfalls in anticipating and planning for the future. In this concluding section we look into current and future challenges of thinking about the future at the intersection of politics and academia. We do this going back to the four context factors introduced at the beginning of this concluding chapter (see Figure 14.1). We end our discussion of the complex interactions and feedback-loops between the politics and science of the future with a short reflection on some of the key trends in these four areas.

Predictive imagination emerges in a specific cultural, institutional, and historical setting. Most methods and practices of prevision discussed in this book emerged in a Western context – other cultural contexts have their own repertoire of dealing with the future. Yet as alternative visions of the future are increasingly negotiated at the global level – between Western and non-Western future visions – and will potentially be integrated into global politics and governance, understanding how different cultures think about the future becomes more important. The comparative relationship of varying cultures with the future thus deserves further study, as do the questions in which visions of order (in an anarchic world or in institutions) and how (through cooperation or conflict) future visions will be negotiated at the international level, especially between great powers and large societies.

Yet the question of who and where future visions are negotiated is relevant at the level of domestic politics too, precisely because the fragmentation of authority and accountability in addressing complex, interconnected, and transnational social challenges represents one of the key challenges for government and governance. State, society, and industry increasingly share responsibility in the day-to-day governance of technology, markets, health, and even in such fields as disaster preparedness, as the shift to precautionary politics and the rise of the concept of resilience across many policy fields demonstrate. The move to precautionary politics and a more networked approach to governance can be observed at both ends of the predicted time horizon, the very long one in the context of climate change and the very short one in the context of adapting to rapidly emerging technologies.

The demand for policy-relevant work in general and scientifically robust future-oriented knowledge in particular will keep rising – but the demand will likely shift from a case-by-case request of policy-makers to a more continuous collaboration, as the new predictive technologies are becoming more deeply integrated in the everyday operation of governmental bureaucracies and the day-to-day management of many public issues. The interconnectedness between ever denser socio-technical systems will grow rapidly, as the digitalization of society, economy, and politics takes its course. Society will become increasingly dependent on and interwoven with a rapidly expanding cyberspace, which in turn will be interlinked with space-based and other newly emerging technologies in the fields of quantum computing and artificial intelligence. Because these technologies will in large part be developed by global technology firms – and not public universities – the role of the private sector in assembling future knowledge will keep growing as well (Dunn Cavelty and Wenger 2019). Yet this also means that a growing portion of future knowledge will fall under trade secrets and non-disclosure agreements and lack transparency and accountability as regards epistemological premise, method, and data.

The historical shift away from a public model of prediction to a private model of prediction is linked to the growing computing power and the algorithmic exploitation of big data that come with the promise of controlling and managing the future at an unprecedented scale and speed. Yet it is problematic for society and democracy if the development and application of these new AI tools is dominated by a few global technology firms – that are operating under a steep safety–performance trade-off – and a few great powers – that perceive these technologies as a strategic resource (Dafoe 2018). In short, the dependence of the public sector on private providers of predictive tools and knowledge is increasing. As a corollary, there is a growing need for systematic and transparent evaluation of these tools and, especially in a democratic setting, governments are expected to ensure that these tools will be used in a responsible, inclusive, and peaceful way (Fischer and Wenger 2019). In addition, the growing role of private providers of scientific knowledge about the future also affects anticipatory practices, because with their applied and problem-centred outlook and flexible collaborative style they are well positioned to contribute to transdisciplinary modes of knowledge creation.

Academia and the traditional university system – based on a disciplinary organization of knowledge production and perceived as autonomous of society and politics – are changing too, shaping and shaped by the rapid transformation of society, economy, and politics. If scientists in universities want to become more policy-relevant, they must become more accustomed to work in interdisciplinary settings, because future knowledge is inherently multi-disciplinary. For example, more research at the intersections of computer science, mathematics, economic, and political science is needed in order to develop sustainable socio-technical systems. In addition, universities need to expand their policy-relevant tool box and define how they want to work in transdisciplinary settings at the intersection of basic and applied research, where multiple producers and consumers of future knowledge come together. It is in the interest of science and society that public universities are not marginalized in foreseeing and planning for what is to come.

Politics and science in a democracy depend on each other, especially as regards assembling and integrating future knowledge into policy and governance. The key contribution of academia is the creation of public, transparent, and peer-reviewed future-oriented knowledge. The key contribution of politics is the design of a deliberative and forward-looking mechanism to integrate this knowledge into public policy and practice. Together, they must choose the method and anticipatory practice so that they fit the object and political purpose of prevision; map, assess, and explore newly emerging predictive tools (Dafoe 2018); and join forces in science diplomacy as a means to build bridges between societies and ensure that the long-term development of these tools is transparent, inclusive, responsible, and sustainable (Fischer and Wenger 2019).

References

Adam, B. (2010) ‘History of the Future: Paradoxes and Challenges’, Rethinking History 14(3): 361–78.

Akin, H. and Scheufele, D. A. (2017) ‘Overview of the Science of Science Communication’, in K. H. Jamieson, D. M. Kahan and D. A. Scheufele (eds) The Oxford Hand book of the Science of Science Communication, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 25–34.

Aradau, C. and van Munster, R. (2007) ‘Governing Terrorism through Risk: Taking Precautions, (Un)Knowing the Future’, European Journal of International Relations 13(1): 89–115.

Assmann, A. (2013) Ist die Zeit aus den Fugen? Aufstieg und Fall des Zeitregimes der Moderne, München: Carl Hanser Verlag.

Bara, C. (2020) ‘Forecasting Civil War and Political Violence’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 177–93.

Bauer, H. and Brighi, E. (2009) ‘Introducing Pragmatism to International Relations’, in H. Bauer and E. Brighi (eds) Pragmatism in International Relations, London and New York: Routledge.

Bell, D. (1964) ‘Twelve Modes of Prediction: A Preliminary Sorting of Approaches in the Social Sciences’, Daedalus 93: 845–80.

Breslin, S. (2011) ‘The “China Model” and the Global Crisis: From Friedrich List to a Chinese Mode of Governance?’, International Affairs 87(6): 1323–43.

Buchanan, B. and Miller, T. (2017) Machine Learning for Policymakers: What It Is and Why It Matters, The Cyber Security Project, Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.

Chilvers, J. (2013) ‘Reflexive Engagement? Actors, Learning, and Reflexivity in Public Dialogue on Science and Technology’, Science Communication 35: 283–310.

Dafoe, A. (2018) AI Governance: A Research Agenda, Governance of AI Program, Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford.

Dewey, J. (1954) The Public and Its Problems, Chicago: Swallow Press.

Doubleday, R. (2008) ‘Ethical Codes and Scientific Norms: The Role of Communication in Maintaining the Social Contract for Science’, in R. Holliman, J. Thomas, S. Smidt, E. Scanlon and E. Whitelegg (eds) Practising Science Communication in the Information Age: Theorising Professional Practices, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 19–34.

Dunn Cavelty, M. (2020) ‘From Predicting to Forecasting: Uncertainties, Scenarios and their (Un)Intended Side Effects’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 89–103.

Dunn Cavelty, M. and Wenger, A. (2019) ‘Cyber Security Meets Security Politics: Complex Technology, Fragmented Politics, and Networked Science’, Contemporary Security Policy 41(1): 5–32.

Dusdal, J. (2017) Welche Organisationsformen produzieren Wissenschaft? Expansion, Vielfalt und Kooperation im deutschen Hochschul-und Wissenschaftssystem im globalen Kontext, 1900–2010, Doctorate Thesis, Luxembourg: University of Luxembourg.

Edenhofer, O. and Kowarsch, M. (2015) ‘Cartography of Pathways: A New Model for Environmental Policy Assessments’, Environmental Science and Policy 51: 56–64.

Edwards, P. (2010) A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ewald, F. (2002) ‘The Return of Descartes’s Malicious Demon: An Outline of a Philosophy of Precaution’, in T. Baker and J. Simon (eds) Embracing Risk, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 273–301.

Ferdinand, P. (2016) ‘Westward Ho: The China Dream and “One Belt, One Road”: Chinese Foreign Policy under Xi Jinping’, International Affairs 92(4): 941–57.

Fischer, S. C. and Wenger, A. (2019) ‘A Neutral Hub for AI Research’, CSS Policy Perspectives 7(2), Zurich: Center for Security Studies (CSS).

Fukuyama, F. (1992) The End of History and the Last Man, New York: Free Press.

Gavin, F. J. (2020) ‘Thinking Historically: A Guide for Policy’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 73–88.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P. and Trow, M. (1994)

The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies, London: Sage.

Grunwald, A. (2014) ‘The Hermeneutic Side of Responsible Research and Innovation’, Journal of Responsible Innovation 1: 274–91.

Hellmann, G. (2020) ‘How to Know the Future – and the Past (and How Not): A Pragmatist Perspective on Foresight and Hindsight’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 45–62.

Hölscher, L. (ed.) (2017) Die Zukunft des 20. Jahrhunderts: Dimensionen einer historischen Zukunftsforschung, Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag.

Horowitz, C. (2020) ‘Future Thinking and Cognitive Distortions: Key Questions that Guide Forecasting Processes’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 63–72.

Jacob, M. and Hellström, T. (2000) The Future of Knowledge Production in the Academy, Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Jasanoff, S. (2015) ‘Imagined and Invented Worlds’, in S. Jasanoff and S.-H. Kim (eds) Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Jasanoff, S. (2020) ‘Imagined Worlds: The Politics of Future-Making in the 21st Century’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 27–44.

Jasanoff, S. and Kim, S.-H. (eds) (2015) Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Jasper, U. (2020) ‘The Anticipative Medicalization of Life: Governing Future Risk and Uncertainty in (Global) Health’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 122–40.

Jervis, R. (2010) ‘Why Intelligence and Policymakers Clash’, Political Science Quarterly 125(2): 185–204.

Jones, L. and Zeng, J. (2019) ‘Understanding China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”: Beyond “Grand Strategy” to a State Transformation Analysis’, Third World Quarterly 40(8): 1415–39.

Katzenstein, P. J. and Nelson, S. C. (2020) ‘Crisis, What Crisis? Uncertainty, Risk, and Financial Markets’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 141–57.

Klinke, A. and Renn, O. (2002) ‘A New Approach to Risk Evaluation and Management: Risk-Based, Precaution-Bases, and Discourse-Based Strategies’, Risk Analysis 22(6): 1071–94.

Leese, M. (2020) ‘“We Do That Once per Day”: Cyclical Futures and Institutional Ponderousness in Predictive Policing’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 213–25.

Lemos, M. C. and Klenk, N. (2020) ‘Uncertainty and Precariousness at the Policy– Science Interface: Three Cases of Climate-Driven Adaptation’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 107–21.

Lentzos, F., Gouyon, J.-B. and Balmer, B. (2020) ‘Imagining Future Biothreats: The Role of Popular Culture’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 158–76.

Li, Y., Chen, J. and Feng, L. (2012) ‘Dealing with Uncertainty: A Survey of Theories and Practices’, IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 25(11): 2463–82.

Maasen, S. and Weingart, P. (2005) ‘What’s New in Scientific Advice to Politics? Introductory Essay’, in S. Maasen and P. Weingart (eds) Democratization of Expertise? Exploring Novel Forms of Scientific Advice in Political Decision-Making, Dordrecht: Springer, 1–19.

Maull, H. W. (ed.) (2018) The Rise and Decline of the Post-Cold War International Order, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McLean, C., Patterson, A. and Williams, J. (2009) ‘Risk Assessment, Policy-Making and the Limits of Knowledge: The Precautionary Principle and International Relations’, International Relations 23(4): 548–66.

Mische, A. (2009) ‘Projects and Possibilities: Researching Futures in Action’, Sociological Forum 24(3): 694–704.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P. and Gibbons, M. (2001) Re-Thinking Science. Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty, Cambridge: Polity.

Pielke, R. (2007) The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schimank, U. (2012) ‘Wissenschaft als gesellschaftliches Teilsystem’, in S. Maasen, Kaiser, M. Reinhart and B. Sutter (eds) Handbuch Wissenschaftssoziologie, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 113–23.

Schneider, J. (2020) ‘Predicting Nuclear Weapons Proliferation’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 194–212.

Simandan, D. (2018) ‘Wisdom and Foresight in Chinese Thought: Sensing the Immediate Future’, Journal of Futures Studies, 22(3): 35–50.

Snowden, D. (2015) Cognitive Edge: Making Sense of Complexity, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Wenger, A. and Horovitz, L. (2018) ‘Nuclear Technology and Political Power in the Making of the Nuclear Order’ in R. Popp, L. Horovitz and A. Wenger (eds) Negotiating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Origins of the Nuclear Order, New York: Routledge, 223–39.

Wenger, A., Jasper, U. and Dunn Cavelty, M. (2020) ‘The Politics and Science of the Future: Assembling Future Knowledge and Integrating It into Public Policy and Governance’, in A. Wenger, U. Jasper and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds) Probing and Governing the Future: The Politics and Science of Prevision, London and New York: Routledge, 3–23.

Westad, O. A. (2020) ‘Legacies of the Past’, in D. Shambaugh (ed.) China and the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 25–36.

Zeng, J. (2019) ‘Chinese Views of Global Economic Governance’, Third World Quarterly 40(3): 578–94.

Zhao, S. (2010) ‘The China Model: Can It Replace the Western Model of Modernization?’, Journal of Contemporary China 19(65): 419–36.

Zheng, W. (2012) Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations, New York: Columbia University Press.

This article is the concluding chapter of The Politics and Science of Prevision: Governing and Probing the Future. This edited volume by Andreas Wenger, Ursula Jasper and Myriam Dunn Cavelty inquires into the use of prediction at the intersection of politics and academia, and reflects upon the implications of future-oriented policy-making across different fields. Read the volume here.

About the Authors

Andreas Wenger is professor of International and Swiss Security Policy at ETH Zurich. He has been the Director of the Center for Security Studies (CSS) since 2002.

Myriam Dunn Cavelty is a senior lecturer for security studies and deputy for research and teaching at the Center for Security Studies (CSS).

Ursula Jasper is the Policy Officer at Fondation Botna in Switzerland.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.