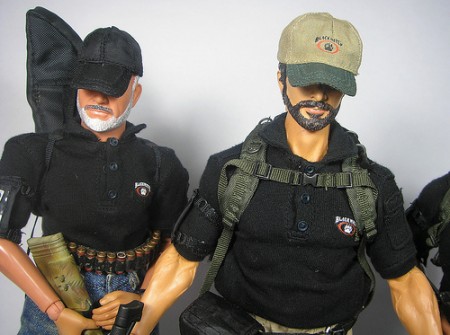

We have all heard about Blackwater and American, English and South-African modern-day “mercenaries” serving in Iraq, protecting targets in the Green Zone and in the Red Zone.

But few of us have heard of the thousands of private military contractors (PMCs) that come from developing countries, such as Uganda or Honduras.

According to some estimates, there are up to 10’000 Ugandans serving in Iraq as security guards. Poorly paid (about $600 a month), they represent a cheap alternative to the $15’000 a month American guard. According to the former Ugandan state minister for labor, the Iraq war and the associated security business brings Uganda $90 million a year, more than their main export product- coffee. The business is beneficial for both, the sending state and the receiving country.

So Ugandans, among others, are serving as cheap security guards in Iraq – what’s the problem?

The problem is that the companies that employ security guards and security contractors in Iraq are making massive profits off their backs. These people are risking their lives for a very small salary, even for Iraq, while the company that employs them is making a massive profit. And the problem is even bigger when, as this Swiss television report shows, some of the security guards are injured: They are not always being paid the compensation they should get. The TV report tells the story of a Ugandan security guard that has lost one eye while working for the Triple Canopy company. According to the company’s regulations, he is entitled to receive more than $200’000 in compensation and months later, he still hasn’t gotten the first cent of this money.

But Ugandans are not the only people concerned by this practice. Peruvian, Fijian, and Filipino private military contractors are also among the top contributors to the PMC business in Iraq and more generally.

The United Nations released a report that “points out that, in some circumstances, the activities of PMSCs and their personnel may result in human rights violations.” But the human rights violations do not only happen in the country that these new PMCs are serving in (abuse scandals being the most infamous example of PMC misconduct), but to the contractors themselves. As cheap soldiers, from vulnerable groups and vulnerable countries and working in a barely regulated field of work, they also suffer, the UN report shows, from partially unpaid wages, ill-treatment and isolation, to a lack of basic necessities such as sanitation or medical treatment when needed.

The Center for International Policy even reported about the case of a subsidiary of Blackwater that confiscated return flight tickets from Columbian PMCs that complained that their salaries were only $1’000 a month instead of the $4’000 promised.

And why is this happening? Mainly because PMCs are located in a grey zone of international and national legislation and because few people have an interest in clarifying the status of these PMCs or to question the PMC industry in general. The ICRC and the Swiss government launched an initiative to clarify the legal status of PMCs, called “Montreux Documents” but this document contains no legal obligations.

We are unlikely to see a legally binding treaty or agreement on this topic in the near future. In the meantime, the abuse and ill-treatment of these “mercenaries” from developing countries will continue and security in countries like Iraq will be built on even shakier moral foundations than before.