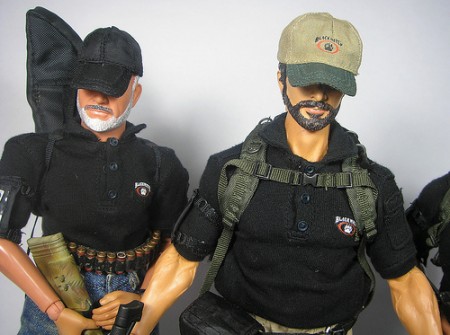

The past few decades have seen a troubling increase in the use of private military and security companies (PMSCs) as a substitute for government forces. Sometimes this “privatization” happens with the express consent of the state and is concentrated in “low-intensity armed conflict and post-conflict situations”, for example the United States’ decision to use Blackwater for security operations in Iraq. In other cases consent is tacit or even irrelevant.

When the state is incapable of protecting its own citizens, it loses its monopoly on violence. The resulting power vacuum is filled by organizations willing to provide the service. Traditionally, organized crime is one such entity, but private security agencies now rise to the occasion just as often. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, for example, the Russian mafia and PMSCs stepped in to supplement substandard domestic law enforcement. A report from a UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries singles out Russian PMSCs precisely for their intertwined relationships with both criminal and law-enforcement structures.