This article was originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) on 11 December 2017.

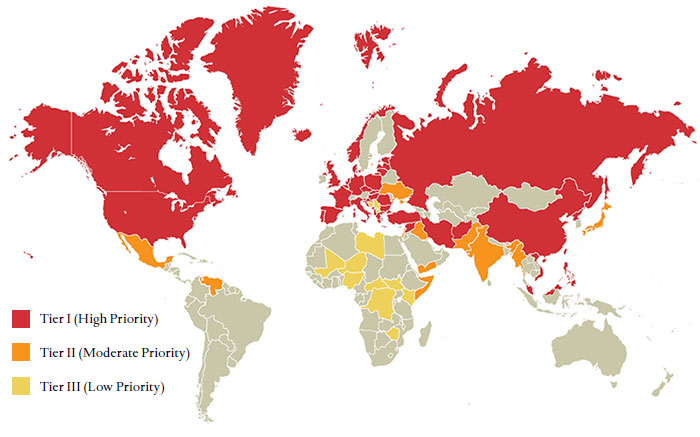

The Center for Preventive Action’s annual Preventive Priorities Survey (PPS) evaluates ongoing and potential conflicts based on their likelihood of occurring in the coming year and their impact on U.S. interests. The PPS aims to help the U.S. policymaking community prioritize competing conflict prevention and crisis mitigation demands.

About the Preventive Priorities Survey

The risk of violent conflict is growing in several regions of the world in ways that could threaten U.S. interests and even trigger a military response. Given the potential costs and harmful consequences of armed intervention, it is clearly preferable that the United States seeks ways to manage the most threatening sources of conflict before it faces the difficult decision to use force. While foreign crises can arise in genuinely unpredictable ways, in many instances the risk factors or warning signs are clear. The opportunity exists, therefore, to take preventive action to lessen the risk of events moving in an undesirable direction and to be better prepared if they do.

With the goal of helping U.S. policymakers identify and appreciate emerging risks of conflict, the Center for Preventive Action (CPA) at the Council on Foreign Relations conducts an annual survey of foreign policy experts to look ahead and provide their best judgment about the dangers that could be brewing just over the horizon. This is the tenth such survey. While there are similar efforts to assess emerging threats and potential crises, the Preventive Priorities Survey is unique in that it is designed to gauge not only the likelihood of plausible contingencies occurring over the next twelve months but also their impact on U.S. interests. Not all potential crises, after all, pose an equal risk to the United States; some are likely to be more threatening than others, and preventive efforts should be prioritized accordingly. This is especially important given how much the press of daily events constricts the time and energy that busy policymakers can reasonably devote to worrying about the future.

Setting priorities can be contentious, however; experts often differ on where attention and resources should be directed. To establish a defensible set of preventive priorities, we first solicited the public to contribute suggestions of what to include in the survey (see the methodology section). From the nearly one thousand responses, we produced a list of thirty contingencies that we judged to be plausible in the coming year. Those taking the survey were also provided with guidelines to help them evaluate each contingency in a consistent and rigorous fashion. The results were then aggregated and the contingencies sorted into three tiers of relative priority for preventive action.

The final results should be interpreted with the understanding that the survey assessed the risk posed by violent contingencies. We excluded all potential contingencies that we considered to be primarily economic or healthrelated in origin or that revolved around potential natural or man-made disasters, while recognizing that such events can harm U.S. interests. Respondents were given the opportunity, however, to write in additional conflict-related contingencies that they believed warranted attention. We have included their most common suggestions as noted concerns.

Finally, it should also be acknowledged that the survey was concluded in early November 2017. The results therefore reflect a snapshot of expert opinion at that time. The world is a dynamic place, and so assessments of risk and the ordering of priorities should be regularly updated. For this reason, ongoing conflicts are monitored on our Global Conflict Tracker interactive, accessible at cfr.org/globalconflicttracker.

Methodology

The Center for Preventive Action carried out the 2018 PPS in three stages:

- Soliciting PPS Contingencies

In mid-October, CPA harnessed various social media platforms to solicit suggestions about possible conflicts to include in the survey. With the help of the Council on Foreign Relations’ in-house regional experts, CPA narrowed down the list of possible conflicts from nearly one thousand suggestions to thirty contingencies deemed both plausible over the next twelve months and potentially harmful to U.S. interests.

- Polling Foreign Policy Experts

In early November, the survey was sent to nearly seven thousand U.S. government officials, foreign policy experts, and academics, of whom more than four hundred responded. Each was asked to estimate the impact on U.S. interests and likelihood of each contingency according to general guidelines (see risk assessment definitions).

- Ranking the Conflicts

The survey results were then scored according to their ranking, and the contingencies were subsequently sorted into one of three preventive priority tiers (I, II, and III) according to their placement on the accompanying risk assessment matrix.

Risk Assessment Matrix

Definitions

Impact on U.S. Interests

- High: contingency directly threatens the U.S. homeland, is likely to trigger U.S. military involvement because of treaty commitments, or threatens the supply of critical U.S. strategic resources

- Moderate: contingency affects countries of strategic importance to the United States but does not involve a mutual-defense treaty commitment

- Low: contingency could have severe/widespread humanitarian consequences but in countries of limited strategic importance to the United States

Likelihood

- High: contingency is probable to highly likely to occur in 2018

- Moderate: contingency has about an even chance of occurring in 2018

- Low: contingency is improbable to highly unlikely to occur in 2018

2018 Findings

Many of the contingencies identified in previous surveys remain concerns for 2018. Of the thirty identified, twentytwo were considered risks last year. Much has changed, however, and several findings stand out:

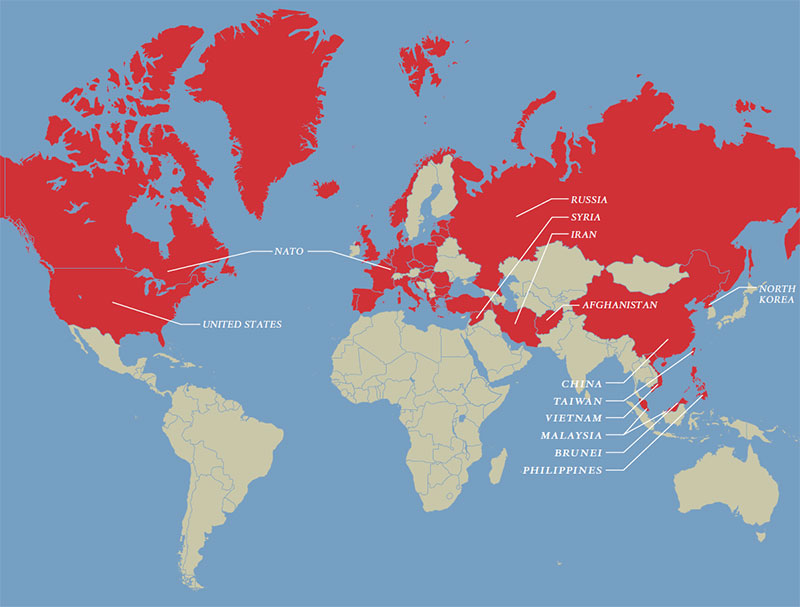

Two new contingencies emerged as Tier I priorities. In light of concerns over increased tensions in the Middle East between Iran and Saudi Arabia as well as both countries’ involvement in the war in Syria, the possibility of an armed confrontation between Iran and the United States or one of its allies has become a top concern. So too is the potential for an armed confrontation over disputed maritime areas in the South China Sea between China and one or more Southeast Asian claimants. These two contingencies join six others as Tier I priorities: the threat of a major terrorist strike or cyberattack against the United States, a military conflict involving North Korea, increased violence and instability in Afghanistan, a military confrontation between Russia and a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member state, and a violent reconsolidation of government control in Syria.

Eight new contingencies appeared in this year’s survey. The risk of intensified clashes between Israel and Hezbollah, increased violence and political instability in the Sahel region of Africa, and escalating tensions or extremist violence in the Balkans represent completely new contingencies this year. In addition to the risk of conflict with Iran, four other contingencies were selected from the initial crowdsourcing: an escalation of sectarian violence and forced displacement in the Central African Republic, growing political instability and violence in Kenya, an escalation of organized crime– related violence in Mexico, and intensified sectarian violence in Myanmar.

Two contingencies surveyed last year received a higherpriority ranking for 2018. In addition to a potential military confrontation in the South China Sea moving up from a Tier II to Tier I concern, the likelihood of continued al-Shabab attacks in Somalia moved up from Tier III to Tier II.

The priority rankings of two contingencies were downgraded for 2018. The intensification of violence between Turkey and various Kurdish armed groups within Turkey and neighboring countries changed from Tier I to Tier II, and the probability of greater violence in Libya following a breakdown of the peace process moved down from Tier II to Tier III.

Three contingencies have evolved significantly since last year’s survey. After the September 2017 Kurdish independence referendum, concerns about instability in Iraq caused by political fracturing and violent clashes among Sunni, Shia, and Kurdish communities have been replaced by apprehension over an escalation of conflict between Iraqi security forces and armed Kurdish groups. Intensification of the civil war in Syria has also been regularly mentioned in previous surveys. The focus was previously on the effects of increased external support for the warring parties, but this year the source of concern has shifted to encompass the violent reconsolidation of government control by domestic actors and a rise in tensions among the parties providing external support.

Eight contingencies assessed last year were not included for 2018. These include an intensification of the political crisis in Burundi, political instability in Colombia following a collapse of the peace agreement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), growing civil unrest and ethnic violence in Ethiopia, political instability in European Union countries exacerbated by the influx of refugees and migrants, military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, growing opposition to the government’s domestic and foreign policy agenda in the Philippines, political instability in Thailand resulting from the uncertainty over royal succession, and increased political instability in Turkey stemming from growing authoritarianism. While the underlying dynamics that led to these contingencies’ inclusion have not disappeared, none were identified as significant concerns in the initial pool of crowdsourced contingencies and thus were not included in the 2018 survey.

Other Noted Concerns

Although the survey was limited to thirty contingencies, government officials and foreign policy experts had the opportunity to suggest additional potential crises that they believe warrant attention. The following were the most commonly cited:

- a reversal of the peace process between the Colombian government and FARC

- an armed confrontation between Russia and the United States or a NATO member over territorial claims in the Arctic

- increased tensions between Qatar and Gulf Cooperation Council countries

- a confrontation between Greece and Turkey over disputed territory in the eastern Mediterranean Sea

- an accidental or intentional clash between the United States and Iran in the Persian Gulf

- destabilization of the Philippines by Islamist militant groups, particularly militants affiliated with the self-proclaimed Islamic State

- political instability and civil unrest in EU countries stemming from nationalist and separatist movements

- increased political instability in Egypt, including terrorist attacks, particularly in the Sinai Peninsula

Tier 1

Impact: high Likelihood: moderate

- Military conflict involving the United States, North Korea, and its neighboring countries

- A deliberate or unintended military confrontation between Russia and NATO members, stemming from assertive Russian behavior in Eastern Europe

- A highly disruptive cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure and networks

- An armed confrontation between Iran and the United States or one of its allies over Iran’s involvement in regional conflicts and support of militant proxy groups

- An armed confrontation over disputed maritime areas in the South China Sea between China and one or more Southeast Asian claimants—Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, or Vietnam

- A mass casualty terrorist attack on the U.S. homeland or a treaty ally by either foreign or homegrown terrorist(s)

- Impact: moderate Likelihood: high

- Violent reconsolidation of government control in Syria, with heightened tensions among external parties to the conflict

- Increased violence and instability in Afghanistan resulting from the Taliban insurgency and potential government collapse

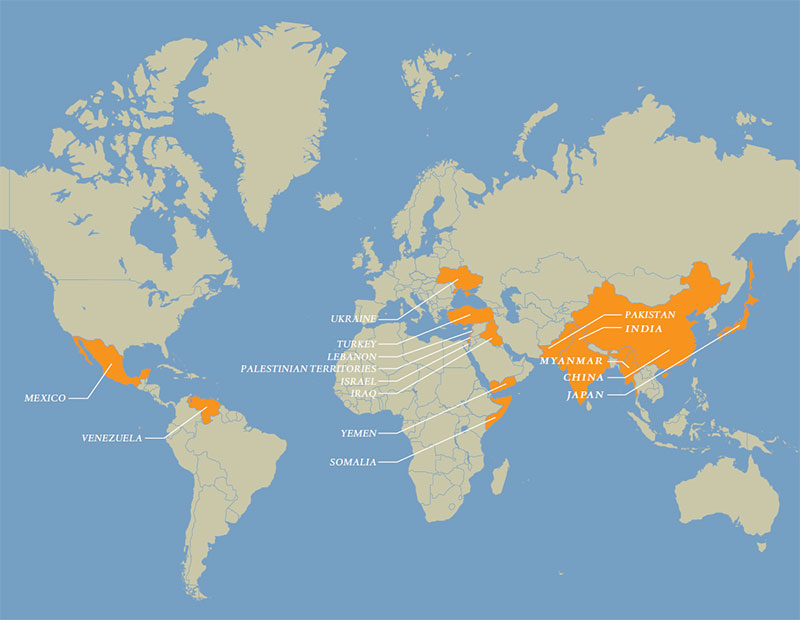

Tier II

Impact: high Likelihood: low

- An armed confrontation in the East China Sea between China and Japan stemming from tensions over the sovereignty of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

Impact: moderate Likelihood: moderate

- Escalation of organized crime– related violence in Mexico

- Intensified violence in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed militias and Ukrainian security forces

- Escalation of conflict between Iraqi security forces and armed Kurdish groups in Iraq

- Intensified clashes between Israel and Hezbollah either along the Israel-Lebanon border or in Syria

- Increased violence and political instability in Pakistan caused by multiple militant groups and tension between the government and opposition parties

- A severe India-Pakistan military confrontation triggered by a major terrorist attack or heightened unrest in Indian-administered Kashmir

- Heightened tensions between Israelis and Palestinians leading to attacks against civilians, widespread protests, and armed confrontations

- Intensification of violence between Turkey and various Kurdish armed groups within Turkey and in neighboring countries

Impact: low Likelihood: high

- Deepening economic crisis and political instability in Venezuela leading to violent civil unrest and increased refugee outflows

- Worsening humanitarian crisis in Yemen, exacerbated by ongoing foreign intervention in the civil war

- Continued al-Shabab attacks in Somalia and neighboring countries

- Intensified sectarian violence between government security forces and Muslim Rohingya in Myanmar and increased refugee influx into Bangladesh

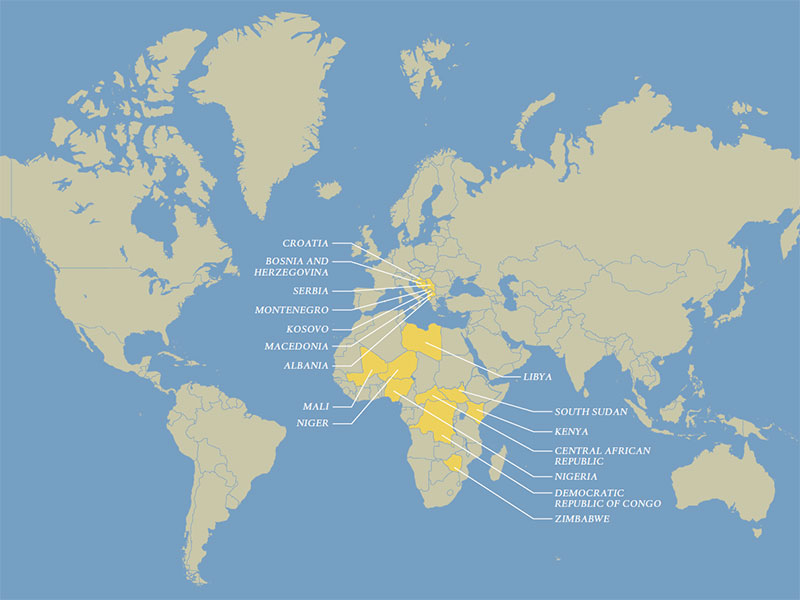

Tier III

Impact: low Likelihood: moderate

- Intensified violence and political instability in Nigeria resulting from conflicts in the Delta region and the Middle Belt and with Boko Haram in the northeast

- Escalated violence in Libya following a breakdown of the peace process

- Escalating tensions or extremist violence in the Balkans—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia—resulting in political instability and armed clashes

- Intensified violence and political instability in the Sahel, including in Mali and Niger, related to increasing militant activity

- Escalation of the civil war in South Sudan stemming from political and ethnic divisions, with destabilizing spillover effects into neighboring countries

- Growing political instability and violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, resulting in continued forced displacement and destabilizing effects on neighboring countries

- Growing political instability and violence in Kenya following the 2017 elections

- Widespread unrest and violence in Zimbabwe related to the succession of former President Robert Mugabe

- Escalation of sectarian violence and forced displacement in the Central African Republic between the Seleka rebels and anti-balaka militias resulting in continued forced displacement and destabilizing effects on neighboring countries

About the Author

Paul B. Stares is the General John W. Vessey Senior Fellow for Conflict Prevention and Director of the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.