“Orthodoxy is experienced in debate and controversies, in those tacit agreements that are masked by overt disagreements.” – Ronen Palan, Global Political Economy: Contemporary Theories.

With the eviction of Occupy groups from their months-long encampments across the globe, and the cold of winter pushing people indoors, the general consensus was that Occupy had failed. Without long-term access to public spaces to practice their namesake tactic, few believed the movement had – or ever could – affect any meaningful change. However, this belief ignores the subtle ways in which the Occupy movement has come to, well, occupy our dialogue.

The Occupy movement grew out of a grumbling dissatisfaction echoed by youth around the world over broken promises from the increasingly globalized and interconnected economy. The broader concerns of the movement have resonated across the globe with people from all walks of life, and were reinforced through conversations over Facebook and Twitter. Every continent but Antarctica has seen its own version of the Occupy protests. Even recent protests that did not adopt the Occupy “brand,” such as the anti-Putin protests surrounding Russia’s elections, can point to it for both tactical inspiration and motivation, even if their specific goals may differ.

From Greece to Chile to the U.S., protesters spoke out against government policies such as austerity cuts, education policies, bank bailouts, and restrictions on internet freedom. With each step, the movement expanded the boundaries of what was acceptable criticism in our civic dialogue. Before Occupy Wall Street, there was little discussion of income inequality, underemployment, and living wages in U.S. dialogue about the economy. In Hungary, India, and Russia, corruption is under the microscope like never before. Protesters in Italy, Canada, and the United Kingdom are forcing a reexamination of the role of the state in support of the arts and university education.

Why did Occupy catch fire now? According to the Bertelsmann Foundation’s recently released Transformation Index, democracy is in retreat around the world, despite an uptick in economic growth. Meanwhile, economic inequality continues to reach ever-higher levels. U.S. income data from Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, shows that from 2009 to 2010, when the recession was declared officially over, the top 1 percent of earners saw wage increases of 11.6 percent, while the rest of the workforce saw their wages increase only 0.2 percent; this was all while inflation increased 2.7 percent. Youth are bearing the brunt of austerity measures designed to protect governments’ and corporations’ bottom line. They accepted astronomically high levels of student loans in the hopes of a job following college, only to run into the lowest levels of employment for 18 to 34-year-olds in 60 years, and little prospect of improvement.

What this means is that the young men and women camping in public spaces seem to have an anarchic streak to them because they no longer see any value in petitioning the established system for change. They have voted; they have called on authorities to address their concerns; they have done everything they were told they needed to do to be successful. Distrust of institutions and political leadership has reached historically high levels, throwing systems around the world into legitimacy crises as policies – rather than successfully addressing citizen concerns – fail over and over again. In response, citizens are seeking to build alternative, community-driven systems. Occupy is on the forefront of the movement, as two branches within Occupy specifically target community ills: Occupy Our Homes and Occupy The Farm.

As families have fallen behind, burdened by debt or having lost a job, home foreclosures have continued at a steady pace; the price of renting is at an all time high, forcing families to give up more of their budget to put a roof over their heads. Occupy Our Homes advocates for the belief that everyone has a right to decent, affordable housing, especially while “we have thousands of people without homes, we have thousands of homes without people.” Across the country, these Occupiers have worked, through non-violent civil disobedience, to disrupt hundreds of foreclosures. However, the group is not only engaging in sing-ins and camp-outs to prevent imminent foreclosures, but they also continue to target the big banks that they say prey on communities in the search for more profits, all while receiving government bailout money.

On April 23rd and 24th, Occupiers targeted Wells Fargo headquarters in San Francisco and Wells Fargo Home Mortgage Division headquarters in Des Moines, Iowa during the bank’s annual shareholders’ meeting to protest the bank’s predatory lending practices and unwillingness to negotiate with those falling behind on mortgages, while allegedly engaging in tax evasion. “Wells Fargo’s mortgage office here in Iowa is making billions in profits every year by kicking hardworking families out of their homes and they aren’t even paying taxes on their ill-got wealth,” said Kenn Bowen, a Vietnam veteran in Iowa, to Laura Flanders of The Nation. “That ain’t right. Wells Fargo should be broken up into smaller, community banks that will put people before profits.”

As inflation rises, so does the price of food. In the United States, increasing numbers of school children go hungry and food bank shelves go empty. To address the increasing hunger in their community, activists are attempting to increase the number of urban farms and the reliance on large agribusiness farms for our food supply. Occupy The Farm began a “Take Back the Tract” movement on the borders of the University of California – Berkeley, when Occupiers took over a plot of prime farming land used for bioengineering research, the results of which are then sold to agribusiness farmers. Instead of leaving the land to be eventually sold to commercial developers, the movement seeks to turn it into an urban hub providing Bay Area residents with a low-cost source of healthy, nutritious food, and in that way, address structural societal ills in health and inequality.

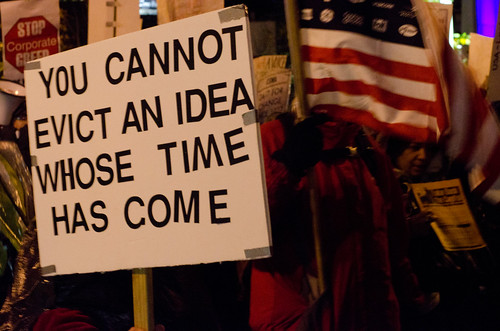

A photo emerged last fall of an Occupier holding a sign reading, “You cannot evict an idea.” The ideas that Occupy has drawn attention to – youth unemployment, quality of life, corporatism, and the failure of the global system – have spread worldwide, and created a new sense of empowerment for the individual vis-à-vis national governments. Now these individuals are banding together to rectify what they see as the failings of the corporate oligarchy and political policy, and save their communities themselves. Perhaps best-selling Brazilian author, Paulo Coelho best exemplified the emerging dialogue when he wrote in his blog, “[W]e don’t need permission to act. We are more powerful than we think we are… We are the revolution taking place.”

Chrisella Sagers is Managing Editor at the Diplomatic Courier.

For further information on the topic, please view the following publications from our partners:

Prospects for Global Growth in 2012

2011: A Strategic survey