This article was originally published by Geopolitical Futures (GPF) on 23 May 2018.

The era of foreign intervention in Syria is coming to an end – at least that’s what Russian President Vladimir Putin said when Bashar Assad, Syria’s president, visited Sochi last week. Granted, Putin’s statement was ambiguous – “in connection with the significant victories … of the Syrian army … foreign armed forces will be withdrawn from the territory of the Syrian Arab Republic” – but Russia’s Syria envoy clarified the next day that Putin was, in fact, calling on all militaries to vacate the country.

Needless to say, this didn’t sit well with Iran, which has been cooperating with Russia in support of the Assad government. Iran rejected Russia’s announcement, insisting that it deployed its military at the behest of the Syrian government. Iran has its own reasons for being in Syria, of course, regardless of what the government in Damascus wants. It means to establish greater command of the Middle East and acquire land access to Lebanon and sea access to the Mediterranean. Even if this territory isn’t under its direct authority, Iran wants to keep Israel and Turkey from encroaching on its borders. In the process, Iran, the de facto leader of Shiite Muslims, hopes to quell Sunni resistance, which, as the Islamic State showed, can be a potent threat.

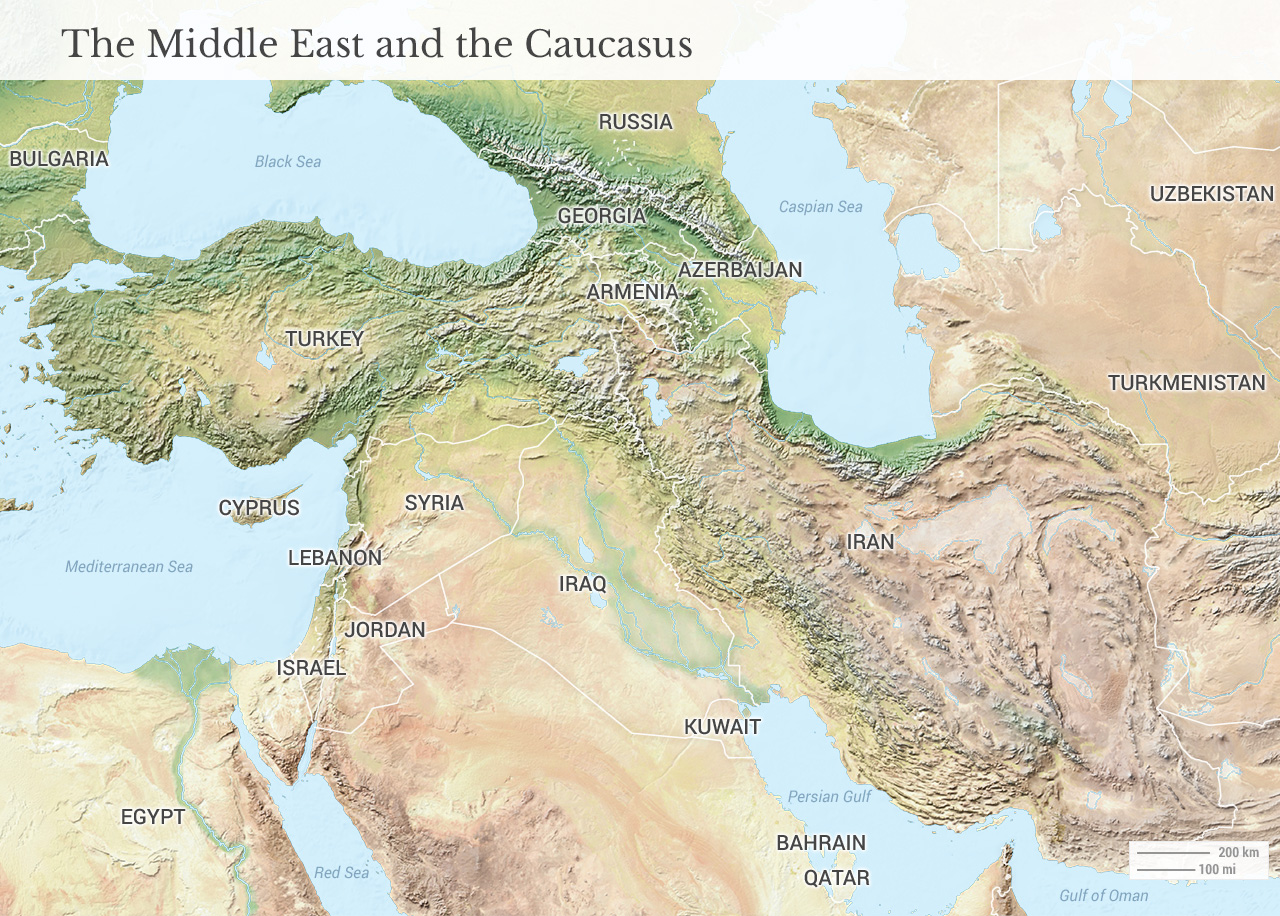

Russia shares none of these goals with Iran. The two may tactically work toward the same goal – keeping Assad in power – but cooperation between Russia and Iran has always been a marriage of convenience, not a true alliance. Russia needs to prevent any one power from controlling too much of the Middle East. A state that eliminates competition in the Middle East would be able to look north, to the South Caucasus, a critical buffer region for Russia. Any power that can gain a foothold in the South Caucasus threatens the North Caucasus, which, in turn, threatens the Russian heartland. Russia must keep Middle Eastern powers competing against one another if it is to prevent any single actor from cementing a position of strength in the South Caucasus.

Russia and Iran’s interests also diverge on oil. The government in Moscow relies heavily on oil and natural gas revenue, so any increase in the price of oil benefits Russia. Iran has a relatively low fiscal breakeven point for producing oil – it can turn a profit when oil is roughly $55-65 per barrel – so it could afford to produce more to keep prices low. Now that the Iran nuclear deal is all but dead, uncertainty around Iranian production has driven up oil prices, giving Russia a little more breathing room. In other words, sanctions on one U.S. enemy, Iran, benefit another, Russia.

Then there’s Israel, with which Russia has friendly relations. Iran’s expansion has begun to invite attacks from Israel, which objects to having an Iranian presence so close to its northeastern border. While Russia is content to bomb rebels in Syria who have no real way to defend against air attacks, it is far more apprehensive about getting caught up in a war against a country with a powerful military and strong motivations to intervene. Israel’s fight isn’t with Russia, and Russia’s isn’t with Israel. But Russia and Iran’s joint support of Assad nevertheless risks pitting Russia against a country it has no interest in fighting.

This explains why Russia declined to retaliate after Israel attacked Russian anti-aircraft installations controlled by the Syrian military. In fact, Moscow didn’t even mention the incident. Sure, the installations in question were outdated, but the fact that Russia decided against selling Syria a more modern air-defense system, the S-300, a day after Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s visit to Moscow illustrates Russia’s desire to avoid providing Syria with the capability to damage Israel’s air force.

But for all the geostrategic reasons behind Russia’s intervention in Syria, Moscow also had a far simpler reason for propping up Assad: It needed to show the Russian people that, despite ongoing hardships, Russia had re-emerged as a global power. After 25 years of losing ground to NATO and the West, it needed to prove that it could counter the United States. It needed to test the preparedness of its military, which has undergone a number of reforms since its 2008 war with Georgia. (For Russia, the war was a success, but it exposed some weaknesses in its air force and in its missile capabilities.)

In Syria, a successful show of Russian force requires a victory and an exit strategy. Claiming that the Syrian military is strong enough to fend for itself, thanks largely to Russian assistance, fits with this narrative. It enables Russia to save face despite the fact it has been in Syria months after it declared its mission accomplished.

It’s unclear when, exactly, Moscow intends to withdraw its forces. When it does, Iran will be left with only a few options. It can continue to support Assad by spending more on the Syrian war, and begin to commit its air force, which, compared with Russia’s, is dated and dilapidated. Spending more is a difficult proposition for a country in the throes of protests over economic issues.

Otherwise, Iran could maintain its current level of support of Assad, but if Russia were to withdraw, Iran would be faced with Israel in its south and Turkey, which also has a modern air force, to its north. Without Russia’s backing, rebels, especially those who benefit from Turkish air support, would stand a better chance of retaking territory that they had lost to Assad.

Last, Iran could reduce its presence in Syria and instead focus on gaining greater control of Iraq, which is much closer to home anyway. That, however, presents its own set of challenges, and in any case risks opening up Syrian territory currently serving as buffer space to be taken by Turkey.

Though Russia hasn’t yet left Syria, its departure will put even more pressure on Iran and open the Middle East up to Turkey. Russia just needs a public relations victory. Iran’s battle is existential, and there are no clear paths to exit in sight. Nevertheless, fissures in the Iran-Russia relationship, even if just rhetorical, reflect the weakness of Russia’s position in the Middle East.

About the Author

Xander Snyder is an analyst at Geopolitical Futures.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.

One reply on “Iran, Russia: What’s at Stake in the Syrian Civil War”

There’s never been a good war but a wise man always thinks what is better for him to do. I think Pres. Putin just used his mind not to harm any on the middle east both parties benefited Russia.