This article was originally published by YaleGlobal Online on 10 August 2017.

By 2024, India will slip past China to become the most populous country and must rapidly prepare for a fast-changing economy.

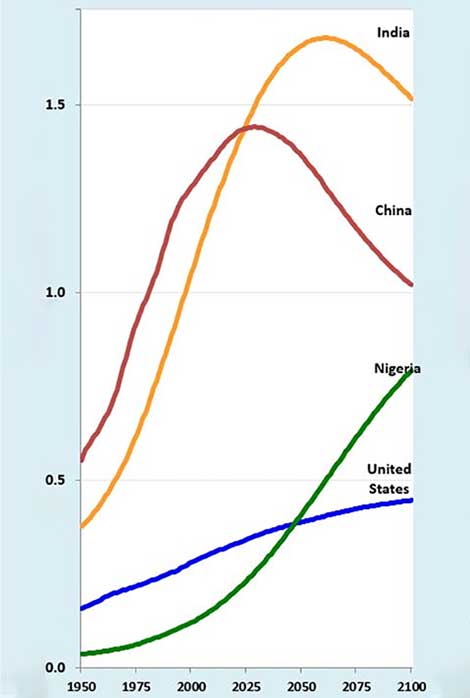

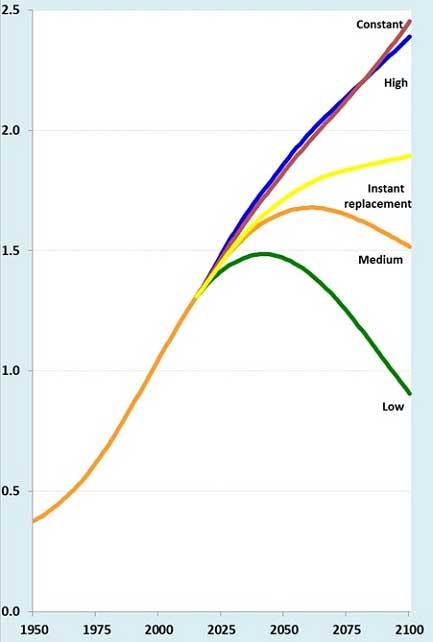

India will likely hold that rank throughout the 21st century. Its population is 1.34 billion, nearly a fourfold increase since independence 70 years ago. China’s population, at 1.41 billion, roughly doubled over the same period. The pace of India’s population growth, now at 15 million per year, is the world’s largest. The two nations alone have more than a billion people, and their population gap is projected to widen to 500 million by 2100. By comparison, the third and fourth most populous countries in 2100, Nigeria and the United States, are projected to have populations of nearly 800 million and 450 million, respectively.

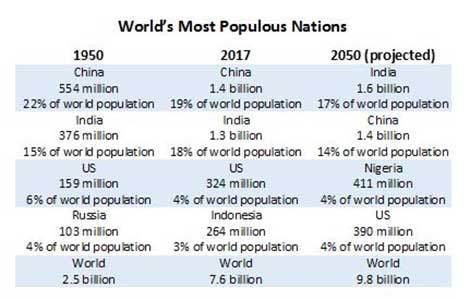

The long-term growth of India’s population, largely a function of fertility rates, is less certain. UN population projections indicate a range of possible scenarios. For example, if India’s current fertility of 2.3 births per woman remains constant, its population would grow to 1.8 billion by 2050 and 2.5 billion by 2100. Even under the instant-replacement fertility variant, with the country’s fertility assumed to fall immediately to 2.1 births per woman, India’s population would reach 1.9 billion by the century’s close.

Population of China, India, Nigeria and the United States, 1950-2100 (billions)

The frequently cited UN medium projection assumes Indian fertility will decline to below replacement by 2035 and remain at 1.8 births per woman in subsequent decades. As a result, India’s population is projected to peak at 1.7 billion in 2060 before declining to 1.5 billion by 2100. The low projection assumes more rapid fertility decline to well below replacement level – about 1.3 births per woman – resulting in India’s population peaking at 1.5 billion around 2040 and falling to 900 million by 2100.

While India’s fertility has declined to about half the level of the late 1980s, that trajectory may not continue. In the past eight years, contraceptive use fell by almost 35 percent, as abortions and use of emergency pills doubled. More specifically, reliance on oral birth control pills, condoms and vasectomies declined by 30, 52 and 73 percent, respectively. In 2017, the Health Ministry launched a campaign to expand use of modern contraception with a focus on population stabilization in 146 high-fertility districts across seven states. With India’s contraceptive prevalence rate at 52 percent, abortion has become a “proxy contraceptive” for many women, especially those from poorer households. For decades, India relied on female sterilization as the primary contraceptive method, funding about 4 million tubal ligations annually, more than any other country. In 2016, the government took major steps toward modernizing that system, introducing injectable contraceptives free of charge in government facilities.

A relatively young age structure also contributes to India’s population growth. The median age in India is 27 years, compared to 38 years for China. Children under age 18 account for one-third of India’s population as compared with one-fifth of China’s.

However, due to fertility declines to near replacement levels, India’s population is also aging. The proportion of elderly aged 65 years and older is expected to double to 13 percent by 2050, and the number of working-age adults per elderly person is projected to fall from 11 to five.

India has achieved notable progress in reducing mortality rates. Life expectancy at birth increased from 44 years in the mid-1960s to 68 years today. India’s child mortality rate at 38 per 1,000 births still lags behind China’s rate of 11. Early marriage and pregnancy still contribute to excessive maternal deaths, and life expectancy of Indian women is eight years less than their counterparts in China.

India and China, unlike most other nations, have significantly more males than females. In both countries, infant mortality was higher for females than males in the 2000s. Skewed sex ratios are due in part to use of prenatal ultrasound scanning to abort female fetuses. The practice of sex-selective abortion, while prohibited, is difficult to eliminate. In coming decades, number of “surplus males” who can’t find brides in India could reach 40 million by some estimates. Contributing to son preference: expected care for elderly, traditional departure of daughters to husbands’ households after marriage and expectations for a bride’s parents to pay a dowry to prospective in-laws.

Such traditions linger in India, where the population is predominately rural in contrast to China’s urban population of 57 percent. Urban populations generally transition more rapidly to lower fertility rates.

India’s rate of urban population growth is expected to climb, partly due to migratory flows, especially youths seeking jobs. By midcentury half of India’s population, about 830 million people, is expected to be urban dwellers, which will challenge government capacities to provide basic services and infrastructure. About one-fifth of the population lives without electricity.

India’s Population by Fertility Variant, 1950-2100 (billions)

Health care also lags with about half of Indian children reported to be undernourished. About two-thirds of them are immunized for diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus, compared to nearly all in China. Tuberculosis in India accounts for over a quarter of reported new cases worldwide, the highest of any country. Another public health challenge: the lack of sanitation facilities for more than half of India’s rural population

More than half of India’s population lives in areas vulnerable to calamities such as earthquakes, floods, cyclones, droughts and tsunamis, and the government continues to develop early-warning systems and promote community preparedness.

International migration plays a negligible role in India’s population growth. Nevertheless, India has the largest emigrant population, with approximately 16 million Indians living abroad and millions more planning to emigrate. India is the world’s largest remittance recipient, receiving on average close to $70 billion annually in recent years. The country implements strong enforcement measures to prevent illegal entry of immigrants, especially from Bangladesh.

Despite high rates of economic growth, forecast to exceed 7 percent for 2017, the benefits do not trickle down to most Indians. Despite India’s relatively large middle class, many struggle to secure basic daily needs. About 25 percent of Indians live on less than $2 a day and the country accounts for one in three of the global population living in poverty.

India struggles to create enough jobs for its growing working-age population. Over the coming two decades, the working-age population is projected to increase by more than 200 million. Over 30 percent of Indians aged 15 to 30 years are neither in employment nor in education and training, more than double the OECD average and nearly three times that of China. At the same time, Indian businesses report shortages of qualified skilled workers. In addition to its efforts to making labor regulations friendlier for job creation, the government must invest in education and vocational training.

Wary about automation and new technologies transforming workplace productivity and redefining the role of workers, education and business leaders recommend a major rethink of curricula and university training programs. India ranks sixth in publications on AI research, between 2011 and 2015, but lacks strategic policies.

India accounts for more than one-sixth of humanity. If the nation’s fertility rates remain unchanged, the population may double to 2.5 billion by 2100. Even if replacement-level fertility were achieved today, the population would still reach nearly 2 billion by 2100. The government must emphasize family planning while improving public health and the status of girls and women – or be hard pressed to sustain high rates of economic growth and meet mounting aspirations of its billion-plus inhabitants.

About the Authors

Joseph Chamie is former director of the United Nations Population Division

Barry Mirkin is former chief of the Population Policy Section of the United Nations Population Division.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.