This article was originally published by the Elcano Royal Institute on 6 June 2019.

As the People’s Republic of China transforms itself into a technological and military superpower, while maintaining a party-state system, there is increasing debate at the heart of the EU about the terms on which relations with the country should be pursued. Pressure has been exerted on the debate by the EU’s main ally, the US, whose strategic rivalry with China is growing daily.

For decades the EU sought to enhance relations with China on the basis that it was a developing country, something that carried two main implications. First, the EU was willing to accept a relationship based on asymmetrical rules that were advantageous to the Asian giant. Secondly it was hoped that China’s socioeconomic development and its incorporation into the value chains of the global economy would translate into greater political pluralism and a general improvement in civil liberties and political rights.

The spectacular progress China has made over the years (it has become the world’s second-largest economy, with the second-largest budgets in research and development and defence) has rendered any attempt to describe it as a developing country as obsolete. There are many voices in the EU, moreover, that consider the situation unsustainable, owing to the size and ambitions of China.

China accounts for 20% of the world economy in terms of purchasing power parity and it is therefore hardly surprising that it has become a trading and financial partner of great importance for many European countries. The relationship has always been complex, offering major opportunities and challenges to European companies and governments. The EU Trade Commissioner, Cecilia Malmström, has frequently pointed out that 3 million jobs in the EU depend on trade with China and that many EU companies obtain competitive advantages thanks to their presence in China and their contacts with Chinese suppliers. However, Malmström has also repeatedly called for an end to the discrimination EU companies suffer in China, given that they face various barriers to entry, are not able to access the same sources of finance or tender for the same state contracts as local firms, and nor do they enjoy the same level of legal protection as their local counterparts.

Despite these problems, the document that guided Sino-EU relations from 2013 onwards, the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation, describes China as a vital strategic partner for addressing the main issues on the global agenda in a multilateral international order. This view was substantially revised on 12 March 2019 in a European Commission document titled EU-China – A Strategic Outlook prior to the European Council meeting of 21-22 March, in which less benign descriptions of China such as ‘economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership’ and ‘systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance’ were added.

This new, more assertive, view of China stems from concern about the fact that the country’s development, driven to a large extent by its international relations, has not translated into the adoption of economic and political governance models prevailing in Europe, but rather into the strengthening of a markedly protectionist party-state system; the latter has aided the internationalisation of its companies in strategic sectors that are closed or barely open in its own market to EU firms, and driven its technological development in economic sectors that play a key role in the fourth industrial revolution, such as digital platforms, 5G, big data and artificial intelligence.

Is EU policy towards China being ‘Trumpified’?

While the change in the European Commission’s narrative on China is highly significant, it is not at all clear how this will translate into the foreign policy of the various member states, nor that the EU or its member states will sign up to the policy of containing China pursued by the Trump Administration and set out at the end of 2018 in a major speech by his Vice-President, Mike Pence.

The member states do not have an agreed stance on relations with China. Indeed, it is possible to identify three distinct positions. In one faction there are countries such as Germany and France, which are driving the more assertive tone in EU policy towards China, and which is also translating into concrete steps such as the implementation of a mechanism to oversee foreign investments. These players are especially concerned, in the European context, by the geostrategic implications of China’s rise and by the loss of their companies’ competitiveness compared to their Chinese counterparts in strategic and high-added-value industries. Moreover, as they have confirmed in a recent manifesto, the two countries advocate the bolstering of EU industrial policy and the role of the state in driving the creation of European champions that ensure the importance of European companies in these economic sectors, preferably in the global marketplace, but at the very least within the EU market.

In a second group there are countries that share the unease of the first, but are more reluctant to increase the level of state intervention in the economy as a means of addressing the economic challenge posed by China. This group includes the Netherlands, the Nordic countries and the UK. Brexit has thus had a major effect on the current EU debate on the nature of relations with China, because the group’s main champion has lost influence within the Union.

In a third group, the majority of countries in the EU’s south and east are more receptive to continue strengthening economic ties with China, even if the Chinese authorities are not willing to embrace economic governance models more attuned to European ones, and choose to continue with an economy that is notably more closed and subject to intervention than its European counterparts. Such countries usually show more interest in attracting Chinese investment and finance than the members of the preceding two groups, because they have more problems in satisfying their financing needs. Moreover, governments that have had disputes with the Commission or with France or Germany on other issues have tended to turn to China to make it clear to their European counterparts that they have other options to diversify their foreign policy. Hungary, Greece and Italy fall into this group.

The most recent illustration of these divisions came with the European Council meeting of 22 March, where discussions on relations with China ended without an official communiqué, while on the very next day the Italian government agreed a memorandum of understanding to sign up to Xi Jinping’s stellar foreign policy project, the Belt and Road Initiative, despite being at the receiving end of repeated lobbying from Washington and Brussels against the initiative. There are now 14 EU member states, including Italy, that have signed some type of agreement to support the initiative (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, the Czech Republic and Romania). The rest (including Spain) reject doing so until such time as the initiative operates in a more transparent and multilateral way, in accordance with the social, environmental and financial sustainability standards recognised internationally and set out in the connection strategy proposed by the EU.

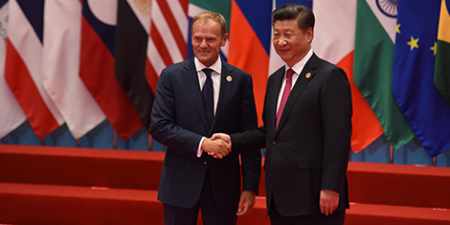

Having said this, it is important to point out that even the players advocating a more assertive reformulation of EU policy towards China, such as the European Commission and the Federation of German Industry (known by its German initials BDI), which published a report on the issue recently, deem it essential to continue bolstering economic and political links with China. This is the same message that Juncker, Macron and Merkel conveyed to Xi during his recent visit to Paris, reflecting the lack of EU support for the US desire to block Chinese technology in the development of 5G networks.

Spain too takes a line that is clearly different from that advocated by the more hard-line members of the Trump Administration, who argue for containment measures against China and a reduction of the interdependence between the two countries. This difference of approach stems from a divergence of interests between the US and European authorities. The former are more focused on perpetuating US hegemony and consequently on the evolution of the balance of forces (including in the military sphere) between the US and China. The European authorities on the other hand place more importance on the absolute economic gains and the role that Beijing could play in consolidating a multilateral international order capable of ensuring the provision of global public goods. Whereas the zero-sum game predominates in the US, there is still a belief in Europe in a positive-sum alternative.

What should the EU do?

The growing rivalry between the US and China forces the EU to reflect and ask itself what role it wants to play within the international community in a context in which the US is going to be increasingly concerned with preserving its hegemony and less with ensuring the provision of global public goods and defending the values it shares with Europe, whereas China is going to push in an increasingly concerted way to impose its models of political and economic governance at an international level.

The EU thus faces four possible scenarios: (1) aligning itself with the US, on the grounds of sharing principles and values, and because, over the short and medium-term, the US still underpins European security; (2) aligning itself with China, because it is the most dynamic market in the most dynamic region and because in the long run China will become the largest economy in the world; (3) the EU not acting uniformly, thus becoming divided and weakened, with some countries taking a lead from the US and others from China, and with recurring internal tensions; and (4) the EU coming closer together and acting as a third pole in a world characterised by systemic strategic rivalry between China and the US and by occasional multilateral cooperation.

The EU should aspire to the fourth scenario, something that entails being committed to taking integration further in order to become a global actor with growing strategic autonomy. Only then will it be able to harmonise and consolidate an effective multilateral international order. The more integrated Europe is –in terms of a banking, fiscal, economic and political union– the more similar will be the interests of the various member states. The process will not be easy and will need to be conducted with sensitivity, empowering the various players to enable them to integrate their interests and thereby feel they are represented.

The Franco-German engine is indispensable for this, but not sufficient. Decision-making about future European champions cannot be the exclusive preserve of Paris and the German industrial cities. Pan-European conglomerates and consortiums are needed along with the distribution of resources in accordance with the specialisations and comparative advantages of the various participants. The watering-down of competition law will not solve anything if it is not accompanied by a greater commitment to funding for education, research, development, enterprise and innovation. Meanwhile, the EU needs to complete the internal market in services and apply the prohibition on unfair state-aid to non-EU companies too. The rules in the single European market must be the same for everyone.

Lastly, Spain, in particular, has a great deal to offer in many areas of this new technological race, from banking, telecommunications and energy, by way of the auto-industry, infrastructure, services (whether involving tourism or otherwise, including education and health) to entertainment, defence and aviation, farming and artificial intelligence. This is the first time in history that Spain has been well placed to play an active rather than a passive role in an industrial revolution. It is a starting point that must not be allowed to let slip.

But it will require a national strategic plan to be developed for the digital era and a new industrial policy and a cross-party national agreement to be forged regarding shared interests. Only then will Spain be able to play a leading role in Europe. Over the course of recent years, Brussels, Berlin and even Paris have requested more input from Spain in EU debates, because they know that Spain is a country convinced that it needs a more united EU to be able to address the major challenges of the 21st century. The rivalry between the US and China is one of these, and Spain is especially well positioned to try to catalyse a consensus on this matter within the Union thanks to its ability to build bridges between member states concerned by the geostrategic implications of China’s rise and the loss of competitiveness among their companies, those reluctant to increase the level of state intervention to combat Chinese competition and those who want to attract a greater volume of investment and finance from China.

This article is also available in Spanish: La política europea frente al desafío chino.

About the Authors

Mario Esteban is Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Professor at the Autonomous University of Madrid.

Miguel Otero-Iglesias is Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Professor at IE School of International Relations.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.

One reply on “EU Policy in the Face of the Chinese Challenge”

Excellent analysis and recommendations; thanks.