This article was originally published by the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI) on 13 June 2019.

In many African countries where civil war raged not so long ago, former warlords are today running for office in elections. This policy note assesses the effect that these warlord democrats have on democratisation and security.

Since the early 1990s, post-civil war democratisation has become the ‘go-to’ mechanism for resolving internal armed conflicts. In an African context, this has resulted in the rise of so-called warlord democrats (WDs) – the former military and political leaders of armed groups, who now take part in national elections. The political influence of WDs is seldom a function of the political parties and state institutions that they represent, but rather of their power as ‘Big Men’. Thanks to the economic resources, (ex-) military networks and political capital that they amassed during the earlier hostilities, WDs are well placed to shape the new post-war order being built. These dynamics have been observed in countries ranging from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (Jean-Pierre Bemba), Rwanda (Paul Kagame) and Liberia (Prince Johnson), to Sierra Leone (Julius Maada Bio), South Sudan (Salva Kiir) and Mozambique (Afonso Dhlakama).

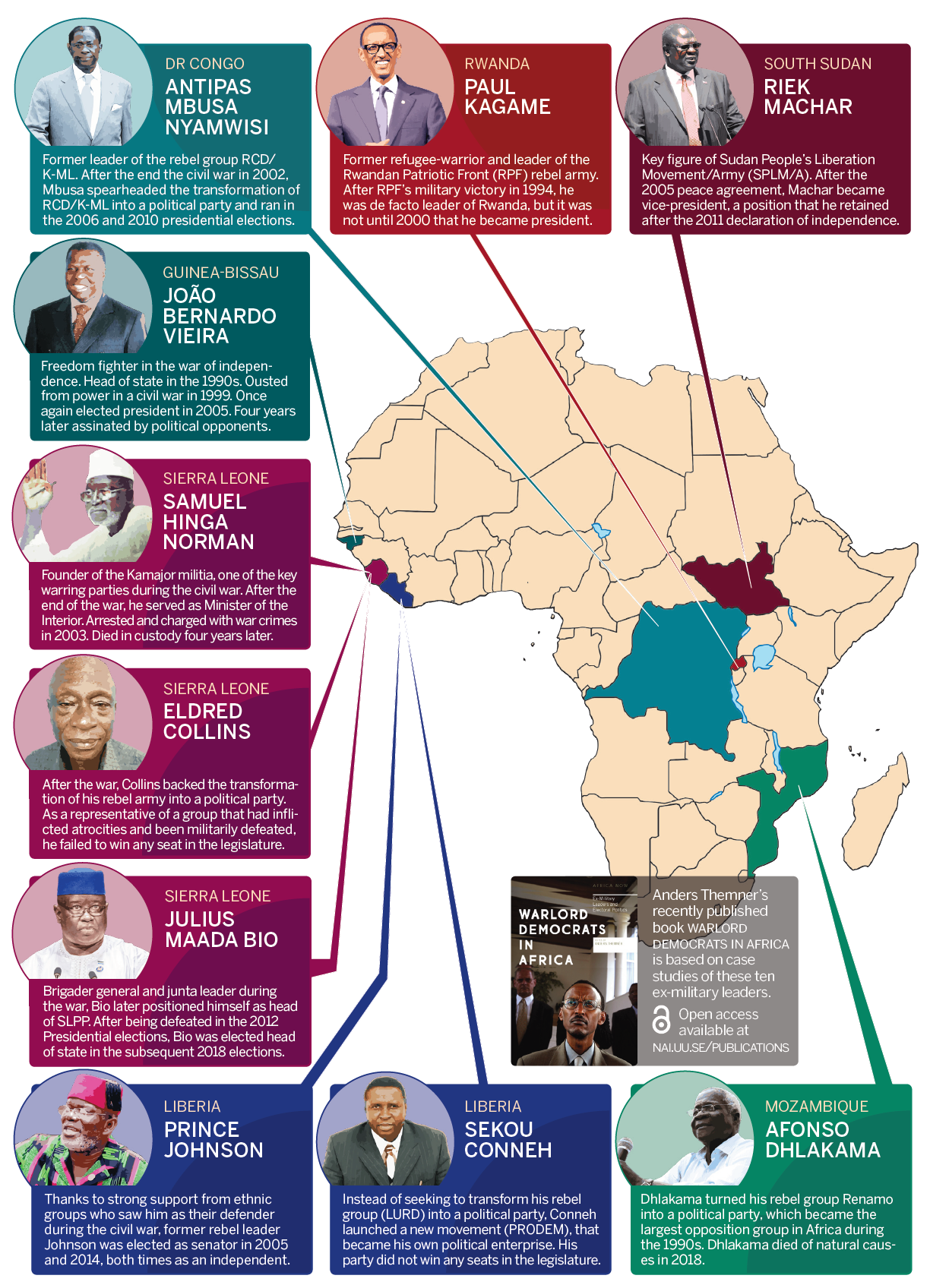

What effect does the electoral participation of WDs have on post-civil war security? On a general note, it is vital to stress that WDs are not per se irrational, reckless actors aiming to undermine the peace process. Violence and threat-mongering is commonly a means of sustaining power and influence in a context where other elites and peacemakers seek to marginalise WDs. In fact, in optimal circumstances, WDs can act as ‘peacelords’, supporting the consolidation of peace and democracy in societies riven by war. We have identified five key policy recommendations for how peacemakers can best relate to ex-military-turned-politicians. These recommendations have been derived from a comparative study of 10 WDs in seven African countries that feature in the edited volume Warlord Democrats in Africa – the DRC (Antipas Mbusa), Guinea-Bissau (João Bernardo Vieira), Liberia (Sekou Conneh and Prince Johnson), Mozambique (Afonso Dhlakama), Rwanda (Paul Kagame), Sierra Leone (Julius Maada Bio, Eldred Collins and Samuel Hinga Norman) and South Sudan (Riek Machar).

Capacity to misbehave and cost of belligerence

One critical aspect to address is the capacity of WDs to misbehave. Here demobilisation is of significant importance. Without easy access to men and women who can be remobilised, it is difficult for WDs to engage in violence. For this reason, it is vital that WDs should not have access to non-state armed factions, ranging from rebel groups and cliques of loyalists in the security forces, to militias and large personal security details. While WDs usually retain some ties with ex-commanders and fighters, informal ex-command structures are more difficult to mobilise than organised armed groups.

On the other side of the equation, the presence of peacekeeping troops or strong security forces (who are under democratic control) can convince WDs of the high costs of employing violence. The societal acceptance of violent methods is also a factor that has an impact on the perceived cost of using violence, and can moderate the behaviour of WDs. In Sierra Leone, the strong popular support for the peace process obliged WDs to damp down their belligerency, in order to retain any chance at the polls.

No trade-off between democracy and stability

A commonly held position among peacemakers is that there is a trade-off between democratisation and stability – i.e. democratic reforms can only succeed once the security situation has stabilised. However, by endorsing semi-autocratic regimes in the name of stability, there is a risk that peacemakers socialise oppositional WDs into becoming autocrats, rather than democrats. If ex-military-turned-politicians operate in a political environment where elections are neither free nor fair, and where threats and violence are employed against them, there is a risk that they respond in kind. It is therefore essential for peacemakers to re-evaluate contemporary strategies that condone democratic deficiencies in the name of stability, and truly and sincerely invest in the democratisation of post-civil war societies.

Restrictions on power-sharing governments

Civil wars often end in power-sharing agreements, where ex-warlords are given cabinet posts in the government. The hope is that such concessions will convince ex-military actors to lend support to peace processes and the building of democracy.

Such solutions can, however, serve to cement the power of armed actors, giving them the resources and influence to unduly, and undemocratically, dominate the political scene. One solution to this problem, exemplified in the Liberian case study below, is to bar members of transitional power-sharing governments from taking part in subsequent elections. WDs not involved in the government then have an incentive to develop a democratic agenda and support elections, rather than engage in rent seeking and consolidating wartime structures. Such restrictions also confront the leaders of armed groups with the difficult decision of whether to enter the power-sharing government or run for election. In the case of Liberia, this served to splinter the armed movements, reducing their influence and their opportunities to mobilise for violence.

See through the rhetoric

Compared to other political actors in a post-war context, WDs are distinguished by their experience of armed violence. However, in most cases WDs are, just like other political elites, first and foremost electoral agents seeking to navigate the uncertainties of post-war transitions. Belligerency – in the form of aggressive rhetoric or sponsoring of low-level violence – should predominantly be seen as a strategy to gain political concessions, rather than as a desire to return to civil war. This behaviour has been observed in a number of cases, including Afonso Dhlakama in Mozambique, Riek Machar in South Sudan, and Sekou Conneh and Prince Johnson in Liberia. Often, WDs engage in this form of bluff when their political influence is diminishing due to waning patronage networks.

When responding to aggressive actions or rhetoric by WDs, it is crucial to bear this in mind. In fact, efforts to marginalise WDs can be counter-productive, as it may push them towards military escalation in order to ensure continued political relevance. Instead, care should be taken to provide WDs with the opportunity to pursue legitimate and peaceful political and economic activities.

Brokers of peace

In order to maintain their political influence, WDs often invest considerable resources in the upkeep of patronage networks. Aside from securing a government position directly, one common way of doing this is to attach oneself to the state, acting as a broker between the regime and local communities. Instead of whittling away the power base of WDs who position themselves as brokers – which peacemakers often seek to do – it might be better to steer such ex-military leaders into becoming brokers of peace. Bridging positions such as these are crucial in post-conflict societies that are fraught with distrust and fear. By formalising WDs’ broker positions – for instance, by appointing them as presidential advisers, mayors and representatives of various state committees or national companies – WDs can be convinced to mobilise their followers in support of peace and democracy. If peacemakers find such concessions too costly, it is at least essential to be aware of the security risks associated with marginalising WDs and to develop strategies for how their aggression can be contained.

Case study: post-civil war Liberia

The Liberian civil wars, which claimed nearly 250,000 lives, came to a negotiated end on 18 August 2003, with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in Accra, Ghana. The CPA regulated the armed conflict between the Government of Liberia (GoL) on the one hand, and the two rebel groups Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) and Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), on the other.

The accord also incorporated a number of oppositional political parties and civil society organisations. After months of negotiations, the agreement set the basis for the institutionalisation of an interim, power-sharing government (National Transitional Government of Liberia (NTGL)) and a national assembly (National Transitional Legislative Assembly). Of particular importance was the fact that the three armed groups were allotted key ministerial posts in the interim government. These positions were highly coveted, since they gave ex-military leaders access to rents derived from international development aid and the exploitation of natural resources, such as diamonds, gold, timber and rubber. The agreement furthermore paved the way for national elections in 2005.

The CPA included criteria about who was eligible to run in the 2005 elections. Article XXV Section 4 of the accord stipulated that: ‘The Chairman and Vice-Chairman, as well as all principal Cabinet Ministers within the NTGL shall not contest for any elective office during the 2005 elections to be held in Liberia.’ This placed the leadership of GoL, LURD and MODEL in a quandary – whether to enter the interim government or not. While cabinet posts guaranteed access to valuable resources – which could be used to sustain patronage networks – not running for office in the election risked politically marginalising the ex-military leaders for the next six years. Complicating matters even further was the fact that there were expectations within the armed movements that those leaders who entered the interim government would share some of the ‘spoils’ with other members, including those who planned to take part in the elections.

The eligibility criteria created severe strains within the armed groups and weakened their chances of continuing to dominate Liberian politics. In fact, while the political successor parties to GoL and LURD – the National Patriotic Party and the Progressive Democratic Party – fared badly at the 2005 polls, MODEL did not even attempt to transform itself into a party. Furthermore, no WDs were among the top contenders for the presidency. The only WDs who had any success were ex-military leaders such as Adolphus Dolo (ex-GoL), Prince Johnson (ex-Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia) and Isaac Nyenabo (ex-LURD), each of whom managed to win a seat in either the Senate or the House of Representatives by running a very personalised campaign. When ex-military leaders who participated in the interim government – such as Thomas Nimely (ex-MODEL) – ran for office in subsequent elections, many lost. Not only were they badly tainted in the eyes of the public for their role in ‘pillaging’ the Liberian state during the time of the interim government, but many lacked the resources needed to run an effective political campaign.

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (CC BY 3.0)

About the Authors

Abraham A. Fofana is a lecturer in political science at the University of Liberia.

Henrik Persson is a research assistant at the Nordic Africa Institute.

Anders Themnér is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.