The division of Cyprus embodies most of the challenges that the Mediterranean region is facing today.

In 1974, following the Greek coup attempt, the Turks invaded the island and now occupy the northern part – called the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus – which is recognized only by Turkey.

Since that time, the frozen conflict over Cyprus has been a sticking point for both the EU and Turkey: the EU for having one of its member states occupied by a foreign country; and Turkey for having its EU accession hopes slowed down.

Cyprus represents a divided region, divided between a Muslim and a Christian community; between an aging side looking for comfort and a youthful one looking for opportunities; between a peaceful Europe with a high GDP and a conflicting Arab world that struggles to adapt to globalization.

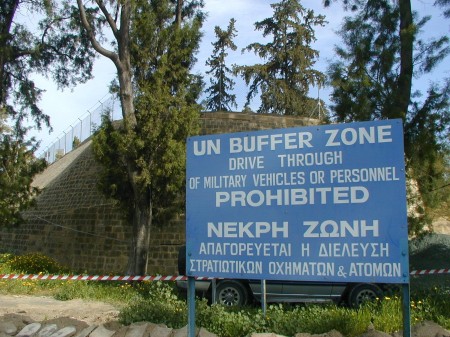

It is also divided by a physical wall, the Green Line, which until 2003, was not possible to cross.

But this relatively recent development isn’t enough. Reunification is not possible without reconciliation. The situation can’t be compared to Germany, where the two parts were willing to reunite despite their differences.

In Cyprus it is quite the opposite: the majority of the inhabitants of the island prefer the status quo. It’s much easier, it doesn’t require a lot of effort, and you can always blame your neighbor for the stagnant situation.

Reconciliation would require tackling issues such as the current Turkish occupation/ colonization; the status of the Turkish minority, economic differences, religious antagonism; and the establishment of a common goal for the whole island.

But Cyprus is much more than a dispute between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. It is a dispute between the northern and the southern side of the Mediterranean Sea.

The Christian north wants to keep its job and economic advantages while ensuring that its southern neighbors don’t cause too much trouble. The Muslim southern part hopes to escape economic and political misery by joining the ‘free’ continent while keeping its identity.

All this is happening within the context of a ‘clash of civilizations’ that seems inevitable.

To move forward, both sides would need to understand themselves as only one region aiming toward a common goal that has yet to be defined. The Barcelona Process and its successor the Mediterranean Union are bound to fail if the parties pull in opposite directions. At the moment, both want to cooperate only to achieve antagonist goals.

The resolution of the Cyprus case may pave the way for furthering cooperation in the Mediterranean region. Until then, it will remain a symptom of a cultural divide that confounds more than it conjoins.