This article was originally published by the Institute for Strategic Studies (ISS) on 12 February 2020.

With arms flows from Libya declining, military barracks and poorly controlled national stockpiles are being targeted.

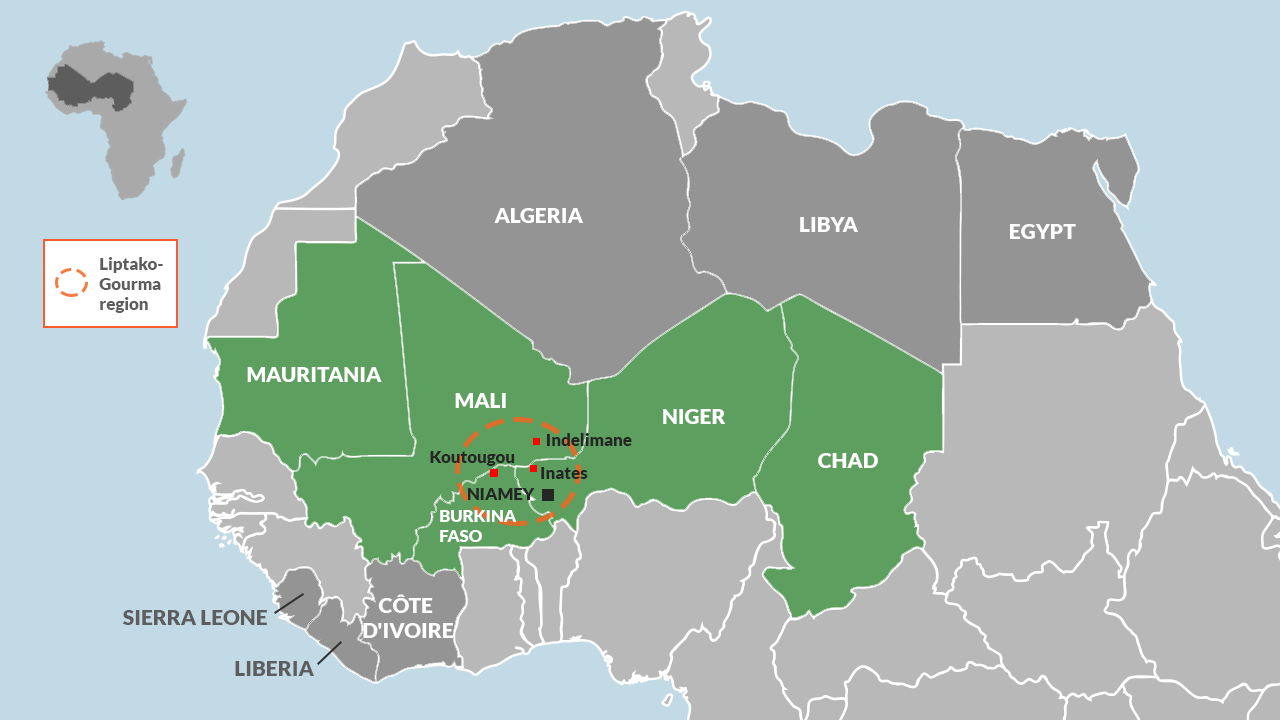

Terror attacks on military outposts in the Liptako-Gourma area where Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger meet are increasingly ambitious and complex. Their frequency and the damage inflicted on defence and security forces is worrying, and raises questions about where the terror groups are sourcing their heavy weapons.

New research by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) on the links between violent extremism, organised crime and local conflicts in Liptako-Gourma reveals that terrorist groups in the Sahel region – of which Liptako-Gourma forms part – are using weapons from the military barracks they’re looting.

Since the outbreak of the crisis in Mali in 2012, the origin of the many weapons circulating in the area has generated speculation. Libya was at one point the main source of arms. Weapons proliferation was linked to the fall of the Muammar Gaddafi regime in 2011. Following the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-led military intervention, Libya lost control of a large part of the stockpiles it had amassed over 40 years.

The transfer of weapons from Libya strengthened armed rebel movements in Mali in 2012. It facilitated the acquisition of arms by terror groups such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, and non-state groups operating in the Sahel region.

Since 2013 however, the flow of weapons from Libya is said to have decreased for various reasons. First, the growing military presence in Mali, as well as the deployment of military reinforcements on the Nigerien and Algerian borders, have led to the interception of arms shipments destined for terrorist and other armed groups.

Second, the intensification of the Libyan civil war has increased the internal demand for arms, which means there are less weapons to export. Nevertheless, arms trafficking networks continue to exploit this channel to obtain other supplies.

But these smuggling networks are just one of the supply channels for non-state armed groups. Another comes from weapons diverted from poorly controlled national stockpiles, as well as arms trafficking from the various crises that have shaken West Africa – in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire and Niger. Some West African ports, identified by the Small Arms Survey as illicit trafficking routes, are also allegedly used for the transport of arms.

More recent attacks on isolated military barracks – during which equipment was stolen – shows that violent extremists are getting their weapons from looted military barracks. Terror groups in the Sahel now launch large-scale attacks on military garrisons or positions, exploiting their vulnerabilities. Using the element of surprise, attackers arrive in large numbers, on motorcycles or in pick-up trucks. They surround the camp and pound it with mortar shells or rockets to disrupt its defences.

Vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices are used to clear the way for the assault on multiple fronts. Soldiers are overwhelmed and the attackers gain control of the outposts and seize weapons, ammunition and other materials.

War footage broadcast by the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims and the Islamic State in the Great Sahara confirm these tactics. In videos, the fighters theatrically display quantities of arms and ammunition stolen during attacks on military camps of Inates in Niger, Indelimane in Mali and Koutougou in Burkina Faso in 2019 (see map above).

This modus operandi, which has enabled terrorist groups to accumulate large stockpiles of ammunition and weapons, is becoming the main source of supply, offsetting the decline in flows from Libya and other former conflict zones.

Securing armouries and weapons stocks has become a real challenge for defence and security forces of states in the Liptako-Gourma region. Rigorous stockpile management in barracks is needed to control the exit of weapons and ammunition, and improve their traceability. To prevent the theft of weapons, stricter measures are needed to ensure soldiers take responsibility for the weapons they hold.

The governments concerned also need to strengthen their operational capabilities and boost soldiers’ morale in the face of violent attacks and equipment theft. Curbing weapons proliferation is a priority and there’s no better time than now for countries in the Sahel to get behind the African Union’s 2020 focus on Silencing the Guns.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. (CC BY 4.0)

About the Author

Hassane Koné is a Senior Research Associate at the ISS Office for West Africa, the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.