The denial that seems to have characterized most of American and European leaders’ assessment of the status of al Qaeda over the last three years seems to be over. Last week two of America’s top intelligence officials openly stated before Congress that the group is morphing, franchising and expanding its reach globally. Similarly, John Sawers, the head of MI6, recently told the British Parliament that “We are having to deal with al Qaeda emerging and multiplying in a whole new range of countries. There is no doubt at all that the threat is rising.”

These assessments are completely different from the tunes heard just a year ago on both sides of the Atlantic. The narrative touting al Qaeda’s demise took shape in Western capitals in early 2011. The first months of the so-called Arab Spring made Western observers swoon with hope at the sight of thousands of demonstrators throughout the Arab world fighting for democracy and adopting none of al Qaeda’s ideas and slogans. Al Qaeda’s message, they argued, had been defeated and the democracies that would rise from the ashes of the authoritarian regimes of Mubarak, Ben Ali, and Ghaddafi would push Arabs and Muslims further away from it.

The May 2011 killing of Usama bin Laden further enhanced this wishful narrative, as it was seen as the final nail in al Qaeda’s coffin. Not only, it was argued, al Qaeda was ideologically rejected by the Muslim masses reversing themselves in the squares to peacefully demand democracy, but the group itself was on the ropes, its leaders incapable of carrying out any significant attack and hiding for their lives. It was increasingly argued that the War on Terror (a term by then tellingly fallen out of fashion) could be replaced by occasional and limited operations targeting specific individuals or groups.

The West, tired of a decade of military engagements and political confrontations, desperately wanted to downscale al Qaeda’s terrorism to the pre-September 11th categorization as a nuisance, a law enforcement matter that required marginal attention. Obama, who had always expressed his criticism of America’s post-9/11 over-reaction and his desire to, instead, focus his attention to a domestic economic and social agenda, led the pack. The Europeans, hit even harder by the financial crisis and wary of the tensions the War on Terror created with its large Muslim communities, were equally eager to downgrade the issue.

Yet many, from Western intelligence agencies to Arab leaders, warned about this wishful thinking. And the events of the last year and a half have proved them right. US officials tried to portray the fact that al Qaeda-linked forces were seizing large swaths of territories in the Sahara and Yemen as momentary drawbacks of the Arab Spring. They also tried to downplay the September 2012 attack on the US consulate in Benghazi that killed ambassador Stevens as a spontaneous riot against a movie offending Islam. But this exercise at denial no longer works when news suggesting that al Qaeda is on the rise come in on a daily basis and from all over the world.

Far from withering, al Qaeda seems to be flourishing throughout a geographical arch that starts on the Atlantic coasts of Africa and ends in the megalopolises of Pakistan but that also encompasses spots in other regions, including the West.

The most impressive gains are arguably in Africa. Groups linked to al Qaeda are active within a gigantic rectangle that has its eastern edges in the Sinai and in Tanzania and its western edges in Nigeria and Mauritania. Within the murky and largely unpatrolled borders of the region’s countries a set of jihadist groups have expanded their reach, boosted by political instability, poverty, and the limited resources of the governments they threaten. Despite having been defeated by the French army in Mali, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its spinoffs still roam the Sahara desert, benefiting from various illegal activities and the influx of Libyan weapons that followed Ghaddafi’s demise. The January 2013 attack on the In Amenas oil complex clearly showed that even the region’s strongest state, Algeria, can suffer severe blows from the franchise. Similarly, the Tunisian government has been fighting a pitched battle against jihadist militias operating in the mountains.

Further east, various jihadist militias exert strong influence throughout Libya, particularly in the Derna region, posing a serious challenge to the country’s feeble national government. And the latest developments suggest that jihadist groups are stepping up their activities in Egypt, attacking not just government facilities but also tourists, possibly replicating the tragic dynamics of the 1990s. In sub-Saharan Africa dynamics are equally troubling. Al Shabaab no longer controls Mogadishu and large swaths of the country, but it still has the capability to be deadly both within Somalia and in neighboring country (as the September 2013 attack against Nairobi’s Westgate mall showed). In Nigeria, authorities seem unable to control Boko Haram and its mass killing of both Christian and Muslim civilians.

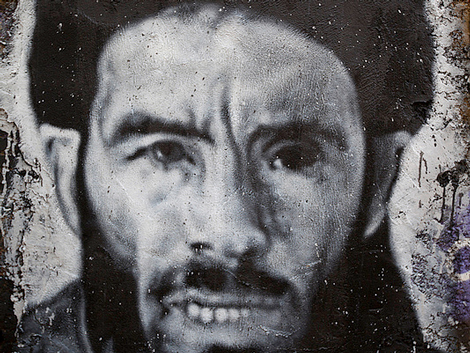

It is incorrect to see all these groups as “pure al Qaeda,” as the degree of affiliation of each of them to the group currently headed by Ayman al Zawahiri varies significantly. Each, moreover, pursues its local agenda with different tactics. Yet, at the same time, they not only occasionally cooperate among themselves, but they all embrace al Qaeda’s ideology and worldview. It is the inability to grasp this latter point that has led many in the West to embrace optimistic assessments of al Qaeda’s demise.

Indeed, as Obama enthusiastically repeated for years, al Qaeda was “on the run.” But that was true only for the “old” al Qaeda, the structured group that carried out the attacks of 9-11 whose leadership was indeed decimated by countless special forces operations and drone strikes in Afghanistan and Pakistan. But it is willful blindness to ignore the fact that the “new” al Qaeda is a decentralized amalgam of freelance groups that embrace al Qaeda’s ideology, see themselves as part of a global movement, but over which al Zawahiri seems to have only limited control. In substance, al Qaeda might be on the run, but al Qaedism is on the rise.

While some saw this alleged lack of central leadership as a sign of weakness, it is not so clear that jihadists see it the same way. Back in 2000, Abu Musab al Suri, one of the most influential theoreticians of the jihadist movement of the last twenty years, argued that al Qaeda was conceived only as a temporary entity, whose very existence was only propaedeutic to the creation of independent jihadist groups throughout the world. “Al Qaeda is not an organization,” he argued, “it is not a group, nor do we want it to be. It is a call, a reference, a methodology.”

In some ways this goal has been achieved, as each group operating in the al Qaeda galaxy acts locally but thinks globally, concentrating most of its energies on fighting local foes but, at the same time, occasionally attacking Western interests and embracing the idea of a global Islamic state.

And indeed state building, at the least at the local level, seems the objective of all al Qaeda-linked groups. Already in his 2001 book Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner al Zawahiri indicated in state-creation as the most important strategic goal of al Qaeda. Over the last few years in Somalia, northern Mali, and in Yemen’s Abyan province, every time an opportunity created by a power vacuum arose, jihadist groups seized chunks of territory and immediately declared them an emirate.

In order to achieve this goal many al Qaeda affiliates have morphed from terrorist groups operating through cells hiding in caves or apartments to full-fledged paramilitary forces engaged in insurgency. And today, thanks to this metamorphosis and the weakness of the forces confronting them, jihadist forces control more territory than they have ever had.

At the same time, all these groups seem to fall in the same error. Once gained control of a territory they squander all the support they initially have from the local population by enforcing their ultra-radical interpretation of sharia with an iron fist. This mistake, which first caused al Qaeda to lose the support of the Sunni tribes in Anbar in 2006, has been repeated over and over. The latest occurrence took place in northern Syria, where the brutal methods utilized by Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham led to its rejection not only by the Syrian population subjected to it but also by other al Qaeda-affiliated groups such as Jabhat al Nusra and even by Zawahiri himself.

But the global jihadist movement has historically proved very adaptable and aware of the mistakes it made in the past. Documents uncovered after the fall of Timbuktu last year showed that the leadership of AQIM had conducted a strategic and self-critical analysis of what had gone wrong in its attempt to create a state in Mali. “The current baby is in its first days, crawling on its knees, and has not yet stood on its two legs,” wrote AQIM leader Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud about the Islamic state “If we really want it to stand on its own two feet in this world full of enemies waiting to pounce, we must ease its burden, take it by the hand, help it and support it . . . until it stands.” It then advocated a more nuanced approach to governance and the introduction of sharia. Similarly, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula has long attempted to establish friendly relations with various Yemeni tribes, also through marriage. And last December, in a clear attempt to improve its image after a faux pas, it publicly apologized for killing civilians in an attack against a hospital attached to the Yemeni Defense Ministry.

The West has finally acknowledged that all these developments clearly indicate that al Qaeda is not defeated, neither ideologically nor operationally. Rather, it has just changed into something different and potentially more dangerous. It is increasingly clear that some the movement’s offshoots pose an existential threat to some of the West’s core allies and interests in the Muslim world. And it is also clear that the West’s own security is still very much under threat from both individuals who have no operational links to any al Qaeda affiliated groups but adopt Qaedist ideology (as in the case of Tsarnaev brothers, the bombers of the Boston marathon) or from individuals who return to the West after fighting alongside jihadist groups (as some of the more than 2000 Europeans currently fighting in Syria could).

The West’s ability to correctly assess the status of al Qaeda will improve only once it will focus less on the group’s tactics and more on the ideological aspects of the movement. As al Suri said, al Qaeda’s essence is not made of weapons and military tactics but by an ideology. And as Mike Rogers, the chairman of the US House of Representatives Intelligence Committee and a fervent critic of the Obama administration’s approach to terrorism stated “the defeat of an ideology requires more than just drone strikes.”

This article was originally published by al Majalla [AR]. Reproduced with permission.

Lorenzo Vidino is a senior researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) and a lecturer at the University of Zurich.

For additional materials on this topic please see:

Countering Terrorism: An Institution-Building Approach for Yemen

Cyberterrorism: The Threat That Never Was

Attacking America: Al Qaeda’s Grand Strategy in its War with the World

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.