This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations on 29 June 2017.

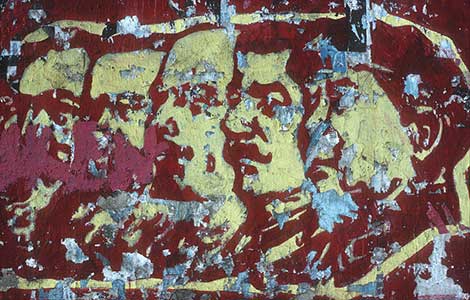

Stalin’s increasing popularity in Russia is worrying, but its importance should not be exaggerated.

This week, yet another poll confirmed Joseph Stalin’s unwavering hold on the popular imagination of Russians. Surveys have documented steadily rising admiration for the Soviet leader in the last several years, but Monday’s open-ended study published by the Levada Center established him as “the most outstanding person” in history, for 38 percent of respondents. Vladimir Putin came in joint second position at 34 percent, alongside the poet Alexander Pushkin.

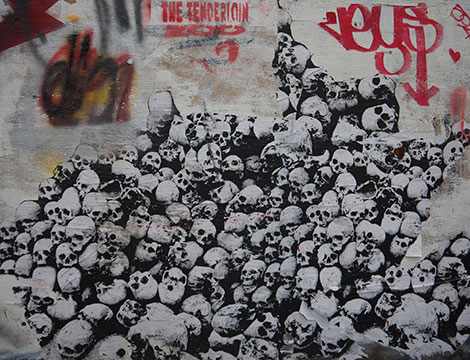

The poll sounds particularly alarming because instead of answering multiple choice questions, respondents were asked to name the first person to pop into their head – not just Russian, but anyone, anywhere. The fact that for 38 percent of people that was Stalin – without the respondent first being prompted – seems to confirm what many have been fearing for some time: that Russians are steadily forgiving and embracing a tyrant who oversaw a system that slaughtered tens of millions of its own people.