MADRID – The approach of the 40th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War has been marked in Israel largely by the recurrent debate about the failures of Israeli intelligence in detecting and thwarting Egypt’s surprise attack. But Israel’s blunder in October 1973 was more political than military, more strategic than tactical – and thus particularly relevant today, when a robust Israeli peace policy should be a central pillar of its security doctrine.

The Yom Kippur War was, in many ways, Israel’s punishment for its post-1967 arrogance – hubris always begets nemesis. Egypt had been so resoundingly defeated in the Six-Day War of June 1967 that Israel’s leaders dismissed the need to be proactive in the search for peace. They encouraged a national mood of strategic complacency that percolated into the military as much as it was influenced by the military, paving the way for the success of Egypt’s exercise in tactical deceit.

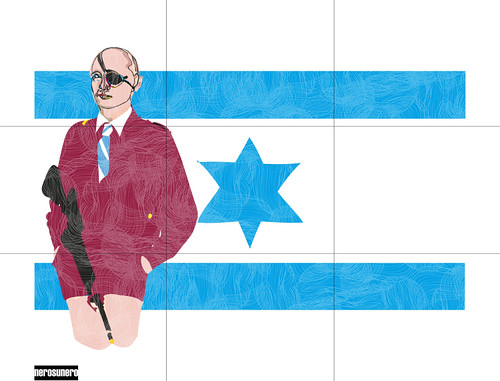

“We are awaiting the Arabs’ phone call. We ourselves won’t make a move,” Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defense minister, said. “We are quite happy with the current situation. If anything bothers the Arabs, they know where to find us.” But when Egyptian President Anwar Sadat finally called in February 1971, and again in early 1973, with bold peace initiatives, Israel’s line was either busy, or no one on the Israeli side picked up the phone.