An outcome that does not make everyone happy is the hallmark of a successful negotiation process, to paraphrase Australian Ambassador Peter Woolcott, president of the United Nations’ Final Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). He and his team certainly achieved that goal. Most states and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) agree that the treaty text does not meet the expectations that were created over the past two decades. However, mitigating this situation is the belief that six years after the ATT has come into force, states will be able to make amendments to strengthen the treaty. Whether this is viable is a question for another day.

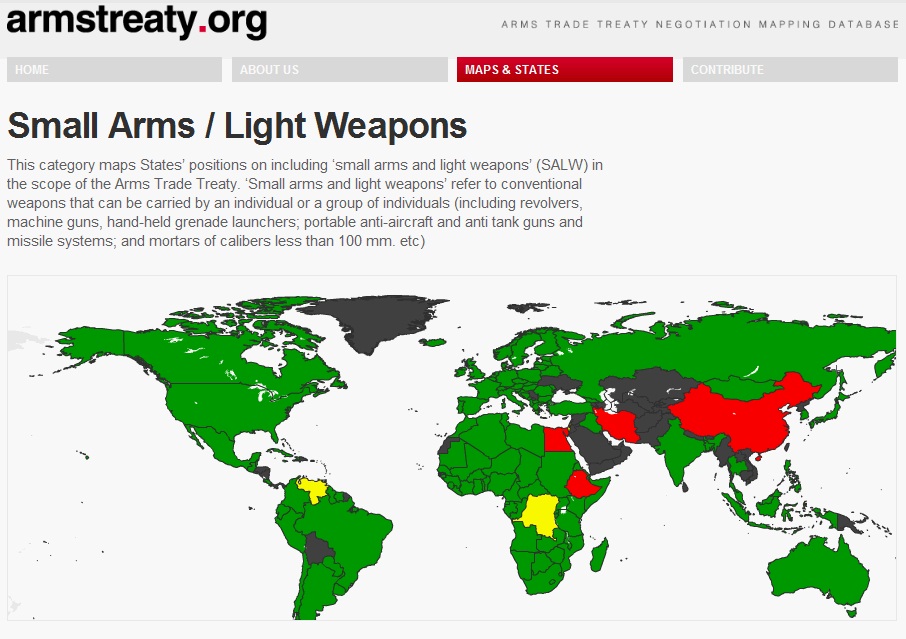

The immediate future of the ATT, in the case of Africa, is to find answers to the question on implementation. Each African state will have to evaluate what resources it has available and then determine what resources are needed to implement the treaty. Several states have been developing capacity on reporting on other treaties and instruments such as the United Nations Programme of Action (UNPoA) and the International Tracing Instrument. These instruments impact on different areas of conventional arms, and small arms and light weapons.