A day after Russia’s President Putin ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Conti, a hacker group suspected to be largely based in Russia and known for financially extorting Western companies, published a message in support of Moscow. The hackers threatened to use “all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures” in retaliation for any “cyberattack or any war activities against Russia”. Soon after, the group sought to dial back this message, claiming not to side with any government.

Already outside of the more permissive environment unfolding under the fog of war, the threat posed by ransomware networks operating out of safe havens had sparked concern. Most notoriously, the REvil group has been associated with several ransomware attacks targeting US critical infrastructure, developing and distributing its malware through a network of affiliates. Triggering a regional emergency on 14 May last year, the group had supplied the malware that encrypted Colonial Pipeline’s billing infrastructure to DarkSide, another hacker group based in Russia, which caused the oil company to shut down its main pipeline on the East Coast for six days to prevent further and potentially longer-lasting damage. Yet, in a brief instance preceding its renewed invasion of Ukraine, Moscow demonstrated an unexpected capacity for collaboration following sustained US efforts pushing Russia to rein in criminal groups: On 14 January, Russia’s domestic intelligence service FSB cracked down on the ransomware-as-service group REvil at US request. How does this development sit within Russia’s now deeply fractured relationship with the US? What new light does the invasion of Ukraine shine on the possible motivations for Russia to round up a ransomware gang at US behest?

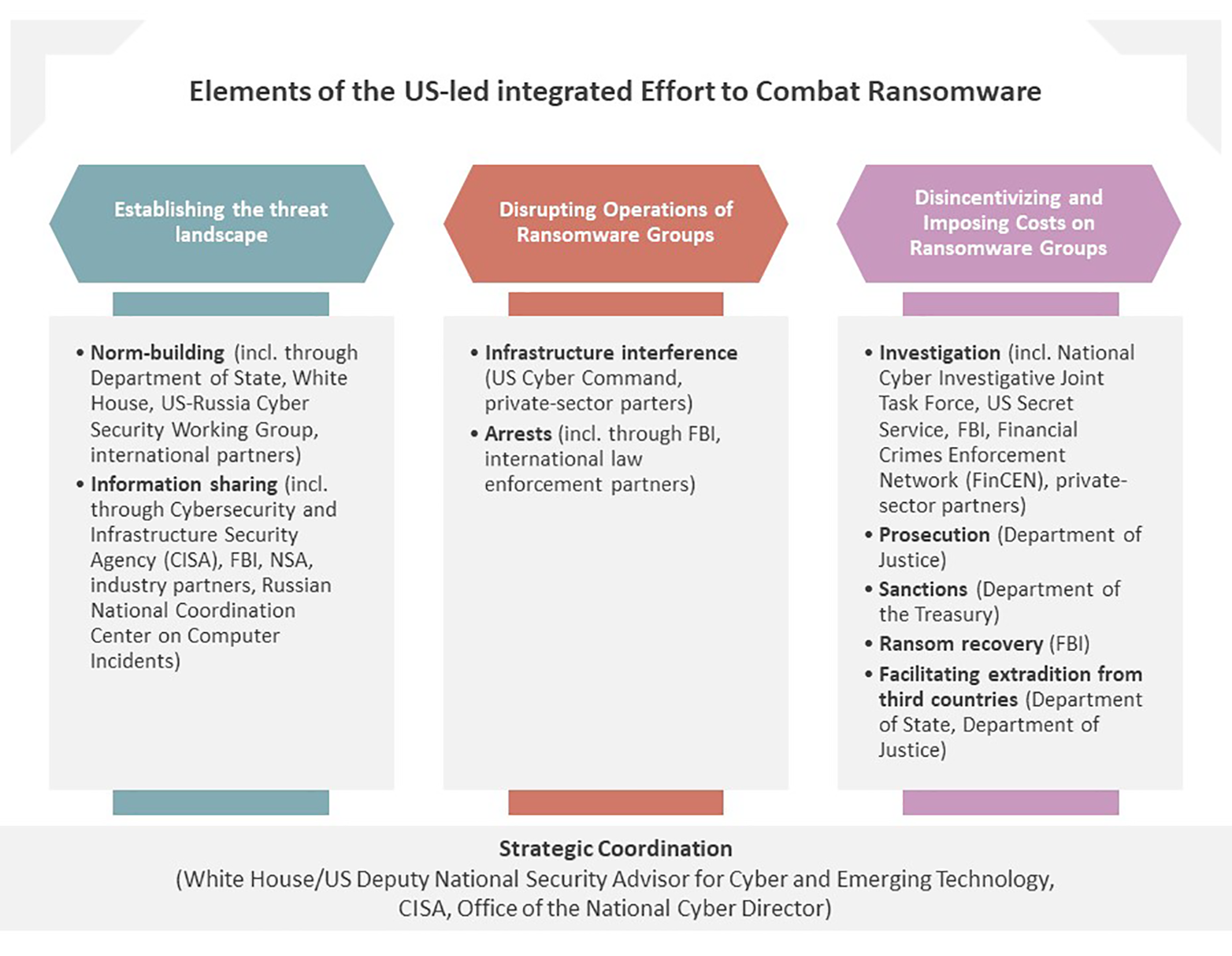

During the last year, the US brought together a framework of measures to counter the threat of ransomware and mitigate its effects. Flanked by measures to strengthen domestic resilience, the effort to get Russia to shutdown ransomware groups in its borders is built on establishing a common perspective on malicious actors through information sharing with Russian law enforcement, to test cooperation and hold Russia accountable. This undertaking has been backed up by the demonstrated will to disrupt the infrastructure of ransomware groups operating out of Russia and to impose judicial and financial costs on the perpetrators and their enablers, including through sanctions. The topic also dominated Biden’s face-to-face talks with Putin during the Geneva Summit on 16 June 2021. At the meeting, Biden stressed that ransomware attacks launched against US critical infrastructure – such as Colonial Pipeline – were off-limits and that the US would hold the Kremlin accountable in case operations emanating from Russian territory continued unimpeded and with impunity.

Theoretically, a channel to share information about incidents and malicious activity with Russia has existed with the creation of the Russian National Coordination Center on Computer Incidents in 2018. In practice, given the center’s subordination to the FSB, the US had refrained from sharing information on Russian hackers but changed course to test Russia’s alleged resolve to act against criminal groups.

The US accompanied its diplomatic outreach to Russia with a reorganization of its counter-ransomware approach, focusing on prosecution, sanctions, and ransom recovery on one hand and offensive cyber operations to disrupt the activities of ransomware groups on the other. This approach elevated the issue from what was primarily a law enforcement responsibility to a matter of national security, assigning it a priority similar to stopping terrorist threats against the homeland.

Using these combined resources against REvil, US government officials announced on 21 October that Cyber Command had forced the group’s digital infrastructure offline. Doubling down on these operational disruptions and highlighting the law enforcement attention on REvil, the Department of Justice unsealed an indictment against a Ukrainian national for deploying the group’s malware suite upon his arrest in Poland on 8 November. Furthermore, the FBI recovered over 2 million USD in ransomware payments from the Colonial Pipeline hackers a month after the attack, signaling that proceeds from extorting critical infrastructure operators are fleeting.

Independent of outside pressure, Russia had little incentive to act against ransomware groups operating from its territory, which by and large focus on targets outside of Russia. In comparison to Russia’s leadership’s domestic security concerns related to drug trafficking, corruption and, above all, regime stability, ransomware groups extorting money in a foreign state may seem of distant interest but can be manufactured into a tool to manage international tensions and manipulate expectations about cooperation. The groups’ disruption of US infrastructure may at times align with Russian interests in exerting pressure on adversaries, as openly indicated by Conti’s announcement following the movement of Russian troops into Ukraine. That these activities are carried out by criminal groups allows the Kremlin to formally claim to not be involved in the attacks.

Offers to cooperate in countering these threats may likewise be a strategic tool for distraction, leading investigative focus and resources astray. Western law enforcement agencies have become wary to respond to indications of collaboration that in the past have proven perpetually elusive. A ploy Russia’s former ambassador to the UN Vitaly Churkin aptly summarized, when his US counterpart Samantha Power sought to call out Russia’s mixed motives following a fraught Security Council debate. Denying the premise, Churkin professed, seemingly in jest, that Russia was “fully sincere about achieving [its] ulterior motive” [p.407].

Possibly in an effort to drive up investments in establishing consultation mechanisms, Russia has long sought to establish equivalent grievances about cybercrime emanating from abroad, while providing little public substantiation. Accusing Western states of neglecting their due diligence, Russia has criticized Germany for leaving over 70 recent legal assistance requests to investigate hacking attempts unanswered. Furthermore, Russia has reported ransomware attacks on its infrastructure that it claims have come from the Netherlands, the US, and Germany, in an apparent bid to justify its own inaction and to put public pressure on accused countries to engage in cooperation. Whether the severity of these alleged attacks rises to those of Russia-based groups against US critical infrastructure remains unclear, as does their true origin.

Russia does not share an intrinsic interest when it comes to combating Russia-based ransomware groups that target foreign states and exert pressure on the US. The conspicuous timing of the FSB’s crackdown on REvil – weeks before the assault on Ukraine and months after the Biden-Putin summit – points to a “Churkinesque” range of alternative interests. The raid may have sought to seize access to high-value systems developed by ransomware actors for use by Russian intelligence services; or to send a reminder to ransomware groups in Russia that their best bet is to place their loyalties with the Russian state – similar to Conti’s announcement that followed soon after.

Ransomware groups frequently commit large-scale data theft, to pressure victims into fulfilling their demands under the threat of publicly releasing confidential material. REvil has a track record of engaging in such double extortion schemes. Access to the trove of data amassed in this process can offer tremendous opportunities for intelligence collection as well as influence campaigns. Disinformation efforts may be fueled by leaks of actual or fabricated documents from organizations that are publicly known to have been compromised. In May 2020, REvil hit a major New York law firm, bringing potentially sensitive documents into its possession. Among these files, the group falsely claimed to have obtained compromising details on Donald Trump – information that purportedly would upend the then president’s re-election chances. In the fall of 2020, concerns about ransomware groups being coopted by Russia for election interference had prompted Microsoft and US Cyber Command, independently of each other, to take down command and control systems of TrickBot.

As Russia’s war of choice against Ukraine is overshadowing possibilities for further cooperation against ransomware groups, the lessons about the forces and circumstances that facilitated a short-lived episode of cooperation should not be lost. The Biden administration’s integrated efforts to combat ransomware attacks signaled seriousness about the issue and a willingness to incur costs to impose costs on the activity of Russia-based groups. The establishment of a US-Russian framework for consultations on ransomware has created the conditions for Russia to use the issue as a tool to manage tension in the relationship irrespective of Russia’s own assessment of the ransomware threat. That existing US-Russia channels facilitated the arrest of several REvil members, including at least one individual directly involved in the attack on Colonial Pipeline, however, also goes to show another point: As a momentary pressure valve that can be tapped in periods of tension, isolated instances of cooperation also have their place in Russia’s rationale. Hinting at this conflicted mix of motives amidst Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Deputy Foreign Minister Syromolotov on 14 March expressed hope that the “spirit of Geneva” would prevail and that the US would “maintain a constructive attitude and common sense”, citing the REvil crackdown as evidence of success.

Any attempt at cooperating with Russia against ransomware groups has been and will be entangled in the ups and downs in US-Russia relations overall. The war against Ukraine has confirmed this underlying assumption in the most egregious way. The opportunities to directly or indirectly leverage the capabilities of ransomware groups with links to Russia for espionage, manipulation, or disruption as well as for managing tensions warrant careful monitoring. This includes ideological rifts. Two days after Conti published its pledge of allegiance, a security researcher that had infiltrated the group leaked internal chats, declaring “Glory to Ukraine!”

About the Authors

Jakob Bund is the Project Lead Cyberdefense and a Senior Researcher in the Risk and Resilience Team at the Center for Security Studies.

Lucia Höfer was a Research Intern for the Risk and Resilience Team at the Center for Security Studies.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.