This article was originally published by the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) in October 2019.

Armed non-state actors (ANSAs) often act as important security-providers in conflict environments but are typically excluded from long-term strategies for peace. To succeed, pragmatic routes to peace should consider how to incorporate ANSAs into longer term frameworks for peace.

Recommendations

International peace operations should:

- Build diplomatic skills to interact with ANSAs who provide security locally and consider what role they can play in building peace.

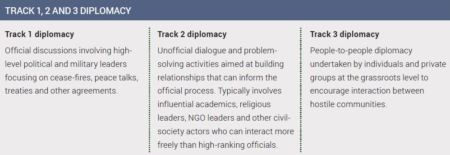

- Establish dialogue with local actors on all levels using track 1, 2 and 3 diplomacy.

- Expand the ‘local agreements strategy’ that has been used successfully in MINUSCA, the UN’s stabilization mission in the CAR.

The UN is currently enhancing its efforts to engage with non-state actors in conflict settings to an unprecedented degree. However, this increased attention is mostly directed towards civil society as a non-violent force for peace. This raises the question of how to deal with armed non-state actors (ANSAs) such as insurgents, rebel groups, terrorist organisations and resistance movements. These actors often play a pivotal role both as security- and service-providers, and as sources of violence in intervention settings. Despite the need to handle ANSAs in such circumstances, no guidelines exist on how to engage with these actors. While ANSAs are often included in peace negotiations, they are typically excluded from long-term strategies for peace. This keeps them confined to a militarized role by locking their power to their possession of arms.

Squaring pragmatic peace with community engagement

The last decade of UN peacekeeping has witnessed a high-level consensus on the importance of involving local actors when striving to achieve sustainable peace in conflict-affected situations. The latest and most prominent indication of this is the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) report of 2015 recommending a shift towards a more ‘people-focused’ approach that includes civil-society actors in addressing security threats and peacebuilding challenges. To promote meaningful inclusion, the UN Secretary-General also called for a strengthening of engagement with civil-society and local communities in his report on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace of 2018. In response to this call, a joint UN-civil society working group is currently developing system-wide Community-Engagement Guidelines for the UN, recommending mandatory strategies for community engagement in intervention settings.

At the same time, peace interventions are becoming increasingly pragmatic. The new pragmatism is reflected in a downscaling of the liberal aims of intervention and reliance on less liberal forms of authority. The increased use of robust tactics in peace operations in recent years has only raised the stakes for local communities, who experience the consequences of violent intervention strategies first-hand. Likewise, the ‘primacy of politics’ doctrine, stressing political solutions in the UN’s approach to fragile and conflict-affected states, suggests that engagement, also with violent actors, should always be considered.

It is therefore striking that no guidelines exist on how to involve ANSAs. Two institutional legacies explain this. First, the UN and associated NGOs select and define civil society as non-violent by definition. Institutionally, this means that much of the work carried out in relation to community engagement excludes armed actors. Secondly, pragmatic peacekeeping operations are structured around a mandate to expand the state’s authority. This makes it difficult for the UN to gain trust among ANSAs as an impartial actor.

Inclusive peacebuilding excludes armed actors

ANSAs are almost always present in the contexts in which current peace operations are deployed. ANSAs are complex actors to deal with, often both perpetrators and security-providers. International involvement in violent contexts where no functioning peace agreement, nor monopoly of violence, exists, begs the question of how to deal with armed actors in areas where civilians have to take up arms to protect themselves or rely on armed factions to provide them with security.

Traditionally, and for many NGOs with contextual knowledge and networks, civil society is defined as unarmed, impartial and independent. These requirements still guide practices of inclusion for many NGOs and UN agencies, but in conflict areas civil society seldomly exists in this pure form. This has led to calls for a broader definition of civil society to include armed actors, but a core challenge is that institutionally the civilian and armed wings of UN missions work separately.

Another challenge is that international actors lack knowledge of and the skills to work with ANSAs.

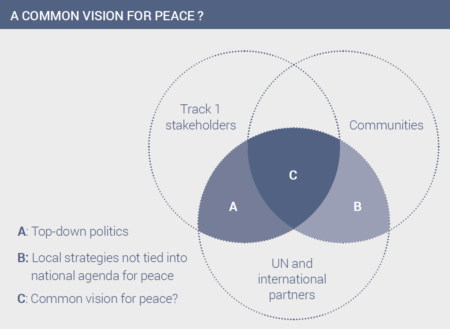

Mission leadership therefore prioritizes interaction with high-level political and military leaders while delegating community engagement to local NGOs. Community-level actors are rarely included fully as political stakeholders, and ANSAs are rarely expected to contribute to longer term strategies for peace. The result is militarized top-down politics combined with sporadic community empowerment projects that are not tied into national strategies for peace and that include only select groups from civil society.

While there is a growing recognition of the problem of addressing armed non-state actors, there is little institutional backing and expertise regarding how to do so. Where inclusivity connotes broad participation, pragmatic peace-making is often limited to belligerents and political elites.

Engagement with ANSAs is often short-term, state-centric and isolated from the broader peace process

Despite the UN’s focus on sustaining the long-term inclusion of communities in peacebuilding, there is a tendency to deal with ANSAs through short-term security-sector reform programmes. In many cases pragmatism has meant doing less from a greater distance and for a shorter period of time. This means that programmes to disarm, demobilize and reinsert ANSAs into the national armed forces have taken place in an ad hoc and time-limited fashion. While often relatively successful, such strategies ignore the underlying political dynamics that caused ANSAs to be formed in the first place, for instance, marginalization, demands for independence or the state’s inability to provide security and social services.

Most peace operations are mandated to support national authorities in extending the state’s authority. This has the potential to generate dilemmas for peacekeepers. When peacekeepers engage in assisting the process of extending the authority of a contested state, they will be perceived as partial, thereby undermining their role in the peace process. There is a need for deep knowledge and great consideration of how to integrate ANSAs into national armies because many ANSAs perceive the state as untrustworthy. Nonetheless the potential gains of bringing the two together are immense.

How can we build peace (together) with ANSAs?

If the UN is serious about pragmatic peace, its mission frameworks must develop more coherent and expansive ways of addressing ANSAs. While UN missions do not necessarily have a comparative advantage locally, local and international NGOs have neither the capacity nor the mandate to work with armed groups. Institutionalizing the political representation of local actors (armed and unarmed) at the mission level is pivotal if pragmatic peace is to succeed in its aims of bringing communities on board. The key is to bring track 1 and track 3 negotiations together, thus combining top-down and bottom-up strategies (see figure: A common vision for peace?). This would ensure that the concerns not only of power-holders but also of constituencies are taken on board in identifying shared goals between track 1 stakeholders, local communities and the UN mission. Bringing these together requires cooperation across the military and civilian components of peace operations.

Most ANSAs are interested in being part of a national political process. This can be used to put pressure on them and gain political leeway in negotiations with them. Many mission personnel have described the importance of identifying something the ANSAs value that the mission can potentially provide as an entry point for dialogue, such as protection, access to certain areas or goods, or development aid. Missions could also indirectly influence ANSAs through the communities and constituencies to which they appeal or from which they draw their legitimacy. For instance, such communities could be invited to the negotiating table and their needs used as conditions for inclusion in the peace process.

At the same time, interaction with armed groups must be balanced by the inclusion of non-violent groups, thus taking all sections of society seriously. Instead of viewing unarmed actors as merely functional in securing the protection of civilians, early warning, monitoring and information-sharing, they must be included as political actors in their own right.

This requires the international community to step up as a political actor, which necessitates mandated support from participating states. This can take the form of providing missions with political support to prioritize protection and engage with ANSAs in the face of objections from host governments, as well as releasing sufficient resources to effectively engage with ANSAs.

Example of Successful Inclusion

The ‘local agreements strategy’ of the UN stabilization mission in the Central African republic (MINUSCA) has managed to stabilize areas and build trust between communities, ANSAs and the state through three important steps.

First, with support from mission headquarters, it has empowered MINUSCA field staff to seek small political victories to enhance the protection of civilians. State authorities in the Central African provinces are weak, but it is the local préfet or relevant government representative who engages in dialogue and signs the agreement.

Second, the ‘local agreements strategy’ emphasizes follow-up with the signatories.

Third, the approach seeks to empower field staff to engage with ANSAs: for example, the mission recently established standard operating procedures for engaging with armed groups, stating that engagements is not merely allowed but expected in furthering the mission’s mandate.

About the Author

Lise Philipsen is a guest researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.