This article was originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) on 1 November 2016.

While much attention is rightly focused on Syria and the Middle East, there are a growing number of refugees in the Western Hemisphere.

The largest group comes from Central America’s Northern Triangle—Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. For each of the past three years between 300,000 and 450,000 Central Americans have fled north. Of these, between 45,000 and 75,000 are unaccompanied children; another 120,000 to 180,000 families (usually a mother with children); and between 130,000 to 200,000 single adults. These numbers peaked in May and June 2014 when more than 8,000 unaccompanied minors crossed the U.S. border each month. 2016 numbers are again rising, with August inflows higher than ever before.

These migrants are fleeing violence (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala are some of the most dangerous nations in the world), poverty, and the economic devastation wrought after three years of record droughts. They are pulled to the United States through personal ties. One study of interviewed minors found 90 percent had a mother or father in the United States. Many of these U.S. residents from Honduras and El Salvador came on temporary protected status (TPS) visas, meaning they can live and work legally in the United States but may not sponsor other family members (including their children).

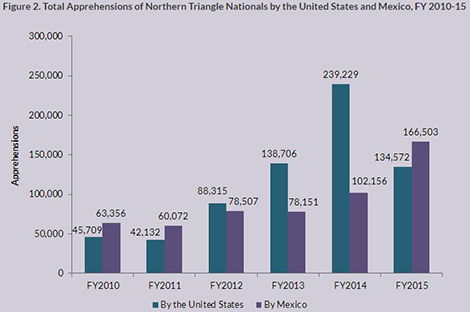

While the overall numbers leaving Central America have been fairly steady, those reaching the U.S. border have fluctuated dramatically. In FY2014, 257,000 were apprehended at the border; this number fell to 149,000 in FY2015. Nearly 200,000 have made it to the southern U.S. border during the first eleven months of FY2016. The differences largely reflect Mexican enforcement and absorption. The Mexican government sent back 167,000 migrants in FY2015, and likely absorbed tens of thousands into its own society. FY2016 numbers look similar so far.

Other nationalities are leaving home as well—many headed for the United States. 5,000 Haitians recently showed up at the San Diego-Tijuana border crossing having traveled some 7,000 miles over land from Brazil (part of the 80,000 Haitians who have migrated to Brazil since the 2010 earthquake). In an effort to stop this exodus, the Obama administration effectively ended Haitian access to TPS visas (given after the earthquake), announcing that the 1,000 still at the border now waiting for immigration appointments and any others that come (estimates are that up to 40,000 more are on their way) will be deported back to Haiti. The order was then delayed—but not repealed—in the wake of Hurricane Matthew.

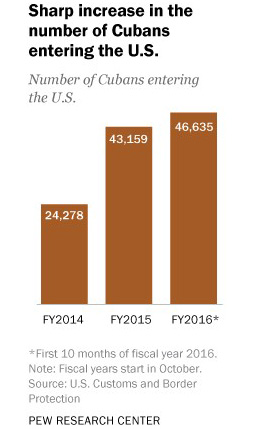

Cuban migration has risen dramatically with changes on the island—since 2013 Cubans no longer need government permission to leave—and due to fears that the United States will end the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act (CCA). Better known as the “wet foot, dry foot” policy, CCA allows Cubans that make it to U.S. soil to immediately receive a visa and access to U.S. services including social security, health care, job training, and even cash transfers. In FY2014, 24,000 Cubans came; FY2015 and FY2016 numbers grew to 43,000 and 47,000 respectively. Many first flew to South American and Central American nations and then began making their way by land north, putting stress on the migrant and refugee services in those nations on their path.

These many flows will likely continue and may grow. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that 3.5 million Central Americans are in need of humanitarian assistance. Haiti (population 10 million) has been without a recognized government since June (the interim president’s term expired and was not renewed). Hurricane Matthew killed hundreds and left another 350,000 people in desperate need. And the number facing “food insecurity”—already 3.6 million—will surely rise given the decimation of harvests throughout southern Haiti.

Venezuela poses a crisis in the making. Outflows have been rising, mostly to Colombia, Spain, and the United States, which has received 10,000 asylum applications in 2016 so far. A recent poll found more than half of Venezuelan voters would leave the country if given the option, following the nearly 2 million that have migrated since Chavez came to power in 1999. If the current economic and political situation implodes, the exodus could quicken dramatically.

All told, hundreds of thousands if not millions of individuals and families in the Western Hemisphere could be forced to leave their country. It is hard to see where they will be welcomed.

About the Author

Shannon K. O’Neil is the Nelson and David Rockefeller Senior Fellow for Latin America Studies and Director of the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.