Africa has a problem of presidents not leaving office when it’s time to do so. The latest illustration of this is the maneuvering of Burundi’s President Pierre Nkurunziza. After 10 years in office, he is attempting to stay on for a third five-year term – in contravention of Burundi’s constitution that limits presidents to two five-year terms.

Nkurunziza’s determination to stay in power has brought the country to the brink of another civil war. (It’s estimated that 300,000 people were killed in Burundi’s ethnically-based civil war of 1993-2005). The government’s hardline response to protests against a third term has resulted in more than 100 deaths, the arrests of some 500 media and civil society leaders, a fracturing of the military, and the exodus of some 200,000 refugees since April.

Unfortunately, Nkurunziza is not alone among African leaders who defy the fundamental requisite of democracy that leaders must step down when their terms expire. In fact, the continent as a whole is in the midst of a wider battle over governance norms. Burundi’s relevance to this larger struggle compels assertive action on the part of key African and Western governments interested in upholding the rule of law.

A wider battle

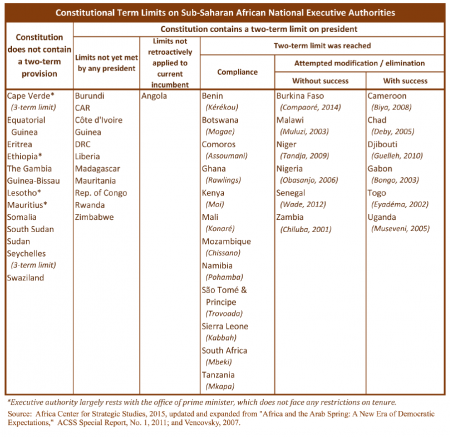

Since 2000, a dozen African leaders have tried to circumvent term limits. Half of these, including Paul Biya in Cameroun, Idris Deby in Chad, and Ismail Guelleh of Djibouti have been successful in eliminating term limits.

Even when African leaders lose elections, it is not assured that they will leave office. After being defeated in Côte d’Ivoire’s presidential elections in December 2010, incumbent Laurent Gbagbo rejected the outcome. Instead, he launched attacks against supporters of his political opponent, Alassane Ouattara, which set the country on a six-month conflict leading to the deaths of over 3,000 people and Gbagbo’s eventual arrest and extradition to the International Criminal Court.

After losing the first round of presidential elections in Zimbabwe in 2008, President Robert Mugabe mounted a nationwide campaign of violence against his political opponents causing the leading candidate, Morgan Tsvangirai, to withdraw from the second round. Mugabe is now in his 35th year as Zimbabwe’s head of state.

This capacity to perpetuate their stay in office explains why nine current African leaders have been in power for more than 20 years, (four of these for more than 30 years). Another 10 heads of state are now into their second decade in office. In addition to the detrimental impact these extended tenures have on building democratic institutions, countries with leaders who have been in power for more than a decade tend to have higher levels of corruption and poorer economic performance.

Several other sitting presidents, including Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of Congo (already in power for 18 years), Paul Kagame in Rwanda (15 years), and Joseph Kabila of the Democratic Republic of Congo (14 years) are expected to try and override their term limit restrictions in the coming year.

The trend is not uniform, however. Half of the dozen African leaders who tried to evade limits over the past 15 years were foiled by populations who rallied against these tenure extensions. Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso is the most recent case. In October, a legislative proposal to eliminate term limits would have allowed Compaoré to extend his 27 years in power. Instead, the announcement immediately set off massive protests. Within days Compaoré had fled the country.

In Nigeria, President Goodluck Jonathan graciously conceded electoral defeat in March, facilitating the first democratic transition between political parties in Africa’s most populous country. Senegalese President Macky Sall declared earlier this year his intent to hold a referendum to limit his mandate by reducing presidential terms from seven to five years.

A key building block in the push for democracy in Africa has been the adoption of term limits. Establishing this precedent is crucial given the continent’s legacy of “big man” politics—the cult of personality surrounding many African leaders that supersedes the rule of law and efforts to establish checks on power. Once ensconced in office, many African leaders so control the levers of power that they are very hard to dislodge.

Through the efforts of reformers, roughly 20 of Africa’s 54 countries now limit presidents to two terms. Another 10 countries, including Burundi, have such provisions written into their constitutions, though they have yet to be implemented. Norms around term limits have been gaining momentum in recent years. Afrobarometer polls show 75 percent of African respondents favor two-term limits for their heads of state. The last successful circumvention of term limits was in Djibouti in 2010.

The struggle to limit Nkurunziza to two terms in Burundi, consequently, has broader significance for Africa’s efforts to create legal parameters for their heads of state. African leaders contemplating extending their terms are watching Burundi closely.

A role for external actors

The African Union adopted the Africa Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance in 2004 setting out Africa’s commitment to strengthening democracy on the continent. Thirty-eight countries, including Burundi, have signed on to the Charter. To uphold these principles, the African Union and its leading members need to take an assertive stand, publicly and privately, when democratic processes are being violated. Failure to do so opens the door to a series of other extra-constitutional challenges to democratic norms across the continent.

Western actors can reinforce the efforts by African reformers by instituting visa bans and asset freezes on African politicians who are deemed to be subverting the democratic process. Aid should be suspended as necessary, especially when these funds bolster the recalcitrant government.

International actors also have a role to play in protecting independent media and civil society, frequently a prime target of regimes wishing to extend their time in power. Any semblance of political dialogue and accountability requires independent voices. There can’t be genuine debate or legitimating elections, not to mention oversight or accountability, without a free press.

In Burundi, some form of regional military intervention will also likely be needed, if only to guarantee a negotiated political settlement. Having this buffer force in place will be important since tensions and distrust are currently so high that any further provocation could trigger a return to full-fledged armed conflict.

Ultimately, democracy is something that must be earned country by country in Africa. Burundi’s civil society has been resilient in trying to sustain the gains toward a multi-ethnic democratic system made over the past decade. Overcoming the stranglehold on power exerted by Africa’s resistant strongmen, however, will require an assist from external partners. Tolerating unconstitutional extensions of power, on the other hand, rewards Africa’s bullies who are unwilling to play by the rules. This, in turn, only invites further political violence.

If Africa can institutionalize respect for term limits, politics on the continent will enter a new era of predictability, with far-reaching implications for the rule of law and stability.

Joseph Siegle is the Director of Research at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.

One reply on “Why Term Limits Matter for Africa”

The case of Laurent Gbagbo cannot be fully apprehended without taking shading light on its context. Unlike the other cases, this one is more complex than you have put it. First, it was agreed that election cannot be organised before the country is reunited. Second, when you say the force of Laurent Gbagbo started firing opposition suppoerter that is to iverlook the fact that the country was in a situation of war where both camps where armed. In such an environment it is Always difficult to apportion reponsabilitites. This is particularly the case is most african setting where one part can infiltrate the other or simply desguise in themselves in civilian clothes to perpetrate massacre. In that political landscape Gbagbo was the only one whose forced were monitored if not scrutinised by the outside world and the other side could have taken advantage of such situation to perpetrate massacre as all will be blame on Gbagbo. By the way i am not an Ivorian but a Congolese but simply wanted to put things into perspective.. Ntumba