Naoto Kan passed a vote of no confidence last week after he had promised to step down soon. (Let’s keep aside the discussion of what he meant by “soon”.) His problem was not so much the opposition, who initiated the vote but only holds a minority of seats in the Lower House. Kan’s authority is challenged from within his own Democratic Party. Already the second prime minister since the party finally managed to take power in 2009, Kan is criticized for his handling of the triple catastrophe that hit Japan in March. (Again, let’s not argue whether the criticism is justified; after all, I want to make a more general argument.)

The Democratic Party holds a solid majority in the crucial Lower House and the next general elections are two years away. Then why is the ruling party so obsessed with changing its leadership? (A bad habit the DPJ seems to have inherited from its predecessor, the LDP.) One answer might be that Japanese politicians care much, probably too much, about opinion polls. Another possible answer is that there is a culture of demission: ministers are expected to step down in order to show responsibility for something that has happened or something they have done. While accountability is a necessary feature of a democratic political system, the threshold for demission seems far too low in Japan*.

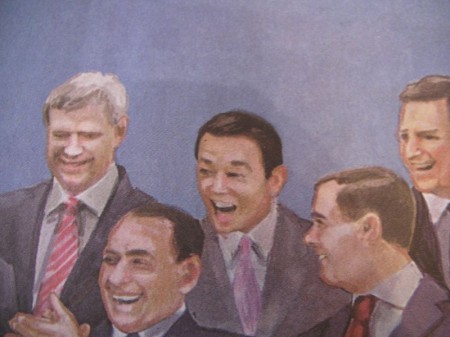

Let’s have a look at one consequence of this culture of demission.

This illustration published on 26 May by the German quality-weekly “Die Zeit” shows a gathering of G8 leaders in spring 2011. Instead of Naoto Kan, who represented Japan at that meeting, the illustration shows a laughing Taro Aso. Yes, Taro Aso, who was Japan’s Prime Minister from September 2008 to August 2009. The illustration is not just based on an old photo; the illustrator cared to replace Gordon Brown by David Cameron (far right). However, he did not bother about Naoto Kan (Kan is already the second Prime Minister since Aso.)

A newspaper like “Die Zeit” should never make such a mistake. When a Japanese TV channel called, they apologized and replaced the illustration on their website with a photo. Yet, what stroke me is that Japanese commentators were not even annoyed by the paper’s mistake. Rather, they blamed their own politicians, in this case Naoto Kan, for not being visible and memorable enough overseas.

One part of the problem is that Japanese prime ministers may indeed seem colorless to outsiders, perhaps with the exception of Jun’ichiro Koizumi and Taro Aso. The other part of the problem, however, is that prime ministers change too quickly to stick to foreign journalists’ minds. Being remembered by journalists would be nice but is not a necessity. But I don’t think it will be easier for foreign leaders to remember who the Japanese Prime Minister was.

I tell you one more time: It’s Naoto Kan. You should at least remember his name when he announces his resignation, as he says, sometime soon.

*There is of course a third answer to that question: Maybe Japanese prime ministers have really been so bad that they deserve replacement. Yet, if each PM is replaced after one year, this raises serious questions about the ability of the Japanese political system to train and recruit its leadership.

For further resources on politicians and political leadership in Japan, see the ISN Digital Library.