This article was originally published by Carnegie Europe on 28 September 2017.

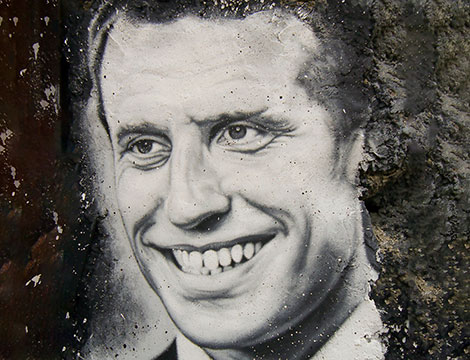

“A sovereign, united, democratic Europe.” This is the vision French President Emmanuel Macron outlined in a landmark speech on September 26, at the Sorbonne in Paris. Calling for a more united and democratic EU is not new. However, for a leader from a major country to passionately assert that European integration reinforces national sovereignty, rather than diminish it, is refreshing.

The last decade has been difficult for the EU, considering the combination of economic and security crises, alongside the 2016 UK decision to leave the Union and the rise of Euroskepticism across Europe. Even so, “We forgot that we are Brussels . . . Only Europe can give us some capacity for action in today’s world,” Macron declared. He bolstered his bold vision with a breathless list of policy proposals, including on European defense.

Macron’s defense vision seems to draw less on traditional French strategic ideology, or a teleological idea of European integration, and more on the urgent strategic necessity for Europeans to work together infused with a strong sense of political opportunity.

Macron’s main military objective is to enable Europeans to act autonomously when needed, complementing NATO’s territorial defense role with a European capacity to intervene abroad, particularly to the south of Europe. He wants EU governments to quickly implement recently agreed initiatives, such as the European Defense Fund and Permanent Structured Cooperation. He would like national armies to be open to soldiers from across the EU, similar to an idea also contained in Germany’s 2016 Security White Paper.

And Macron has three other headline proposals: establishing a common intervention force, a common defense budget, and a common doctrine for action.

No doubt, some defense buffs will dismiss these ideas as vintage French wine in new European bottles. For example, the 25-year-old Eurocorps—a type of common military force based in Strasbourg in which ten countries participate—has sparingly been used. Similarly, EU battle groups, small multinational intervention units on standby since 2007, have never been deployed.

But perhaps the skeptics underestimate the convergence of three factors.

First, the French have added water to their wine since rejoining the NATO military command in 2009—meaning that any remnants of anti-NATO ideology have been superseded by a sharp focus on whatever works best militarily.

Second, although some may disagree, Macron argues that the United States is slowly disengaging from European security just when that strategic environment is becoming more difficult. Europeans will have to take more responsibility for their own security, and they are condemned to cooperate since no one country can cope alone.

Third, French leadership on security combined with German leadership on economics can reboot the Franco-German political engine, which is indispensable for driving the EU forward. Macron wishes to sign an updated Élysée Treaty with the new German government in January 2018, even though it may take until then for the new German coalition partners to agree on their program for government.

Macron’s proposals for a common military force and defense budget are likely to generate more headlines than his idea of a shared military doctrine. This is because they sound like the European army idea so beloved by some federalist politicians (and so loathed by some Euroskeptics).

In fact, his proposals are more akin in spirit to building a de facto military alliance from the bottom-up, which would encompass many forms of intergovernmental military cooperation, than establishing a top-down federal EU army directed by the institutions in Brussels. Most EU governments are instinctively Atlanticist on military matters. Macron wants to strengthen their European intuition.

However, developing an effective shared military doctrine could prove much more difficult than establishing a joint force or common budget. For one, an effective military doctrine should help armed forces to plan, train, and operate together, drawing on a clear worldview and an assessment of threats and capabilities. Ideally, military doctrines orient armed forces for successfully coping with future contingencies. No small task.

For another, developing a national doctrine involves a host of actors, from ministries and armed forces. Combining the disparate perspectives of EU governments is even more challenging. Because of their very different strategic cultures, the danger is that EU governments would produce a dysfunctional doctrine in practice. For instance, the glaring gap between French and German attitudes to military interventions abroad is well documented.

To his credit, Macron acknowledged how difficult this would be, and that he has no red lines, “only horizons.” Similar to U.S. leadership at NATO, however, one solution would be for France—which will be the EU’s leading military power by some distance after the UK leaves the Union—to be the deutschmark of European defense. But will the next German government, not to mention others, let France set the military standard for such an exercise? That’s a very big question.

Counterintuitively perhaps, the departing UK should consider becoming one of Macron’s strongest allies on European defense. London will no longer block EU military initiatives, and its recent position paper on defense post-Brexit made clear that it wishes to keep a very close relationship with the EU on military matters, including being prepared to contribute to operations.

Paris would be wise to support London’s desire for continued close engagement, since British strategic culture is closest to that of the French. Even after leaving, the UK will remain very influential with other EU governments on defense, including—but not only—at NATO, and in ways that could help French leadership. In turn, the UK would be wise to support French proposals, since raising European military standards would benefit NATO too.

An EU-UK agreement on military cooperation post-Brexit can only happen after more progress on the current withdrawal agreement impasse. Nonetheless, the added bonus of a quick and fruitful accord on military cooperation is that it could encourage a more constructive atmosphere for the broader negotiations on the UK’s relationship with the EU after Brexit.

In other words, if Macron’s bold vision is to be realized, other EU governments—you know who they are—will have to become less doctrinaire on defense. Moreover, they will need to take a big leap of faith to embrace a European defense doctrine led by France.

About the Author

Daniel Keohane is a senior researcher at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zürich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.