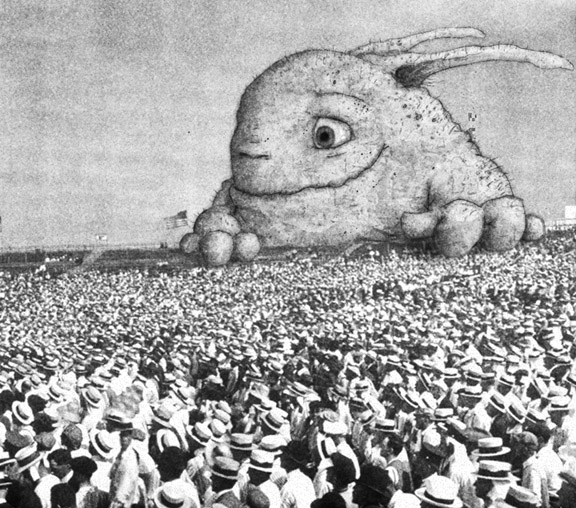

One of my favorite group exercises in mediation training is the monster game. It begins with the participants forming a big circle and designating someone to be the first monster. The monster then speaks the name of one participant in the circle and slowly approaches him/her making a dangerous looking monster face and terrible monster-like noises. The rules are simple: when you are attacked, you are not allowed to move until you’ve said the name of another participant in the circle. You need to do so before the monster physically touches you. If you can’t give a name in time, or you start moving before you have given a new name, you are “dead” and have to leave the circle. The “survivor” then becomes the new monster and the game continues.

While the aim of the game is to stay alive, many participants don’t survive the first few times they get attacked. That’s because when we get scared, our brains don’t function the way they usually do and raw survival instincts take over. Our first reaction is to escape from the threat as fast as we can. That’s also why we regularly use the monster game in mediation training – complex mediation processes may take unexpected turns. For instance, participants might experience emotions such as insecurity and doubt, or even outright fear and panic. These emotions are neither good nor bad, but merely provide us with information that there is a (perceived) monster in the room. However, our immediate and instinctual reaction may set us back in the sensitive mediation processes we are involved in – just as they may inhibit us from producing the name of another participant in the monster game.

Two successful strategies for surviving the monster recur. One is not looking the monster in the eye. By not looking at the monster, we move it into our peripheral view, where we can still see it, but free our mental capacities to think of solutions. The other strategy is to prepare a course of action in advance, for example, thinking of a name before one is under attack. Working on religion and conflict can be a little like playing the monster game.

Moving religion to our peripheral view

It’s easy to become afraid of something you don’t quite understand or know how to approach. When elements identified as “religion” seem to have an impact on conflict, and we don’t know what to do about them, religion turns into a transcendent super-factor that permeates all aspects of life and seems to adhere to unknown metaphysical rules. Keeping religion in our peripheral view could mean adequately analyzing its role in conflict, but not overestimating its influence beforehand. The majority of conflicts that have a religious dimension are not about religion. Calling conflicts “religious” just because actors use religious language or refer to religious practices is misleading.

In these cases, religion influences the conflict by co-forming the actors’ identities – together with ethnicity, language, gender or socio-economic status. Identities are often at the heart of a conflict, because they define who is on your side – and who is not. Statistically, conflicts in which religion is shaping the actors’ identities are far more abundant than conflicts that are inherently about religion. This being said, there are also conflicts about religion. These are about disagreements over religious teachings, sets of beliefs, religious practice, the organization of society etc. When approaching such conflicts, it is crucial to be equipped with a useful way of thinking about religion that can guide us to a course of action.

Preparing ourselves in advance by better understanding what religion is

The first step for preparing ourselves is to become clear on what we understand to be “religion”. The problem of defining “religion” is as old as its socio-scientific discipline comparative religious studies. The scholar Klaus Hock has provided a useful overview of different scholarly approaches to this challenge. A recent publication in the CSS Mediation Resources series nicely distills insights from this academic debate to lay out five key ways for thinking of religion when analyzing its role in conflict. One helpful academic insight the paper draws on is that of theorist Niklas Luhmann. He suggests characterizing religion as one of many societal systems, like economics, politics, justice, or science.

In other words, one might say that all these systems have a different logic that drives them and a different way of making sense of and organizing the world. Understanding religion as a societal system can help us to mentally grasp the strange metaphysical cloud. Conflicts about religion are complex, because religion itself is an elaborate societal system. But so are politics or economics. Sticking to our basic emergency plans like respecting local ownership, a non-judgmental approach and not defining phenomena from the outside but using parties’ self-definitions, are a good starting point when we are still figuring things out.

Understanding religion as a social construction of reality is itself a worldview among many others. But it is one that assists us in regaining our agency in the view of religious dimensions of conflict. In some ways, it

materializes religion by leading our focus away from the theoretical concept of “religion” (that can mean everything and nothing), instead focusing on what specific conflict actors do and say. Concrete actions instead of theoretical discussions will go a long way when trying to find ways of peaceful coexistence among different worldviews. The monster game can help us train to stay level-headed and

prepare helpful strategies for challenging situations we don’t immediately know how to handle.

“Mediation Perspectives” is a periodic blog entry provided by the CSS’ Mediation Support Team and occasional guest authors. Each entry is designed to highlight the utility of mediation approaches in dealing with violent political conflicts.

Angela Ullmann is a program officer in the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich. She works on the Culture and Religion in Mediation Program that seeks to adequately address the interplay of religion and politics in conflict transformation and mediation processes.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.