Image courtesy of Alamy.

Mediation Perspectives is a regular series of blog contributions by the CSS Mediation Support Team and occasional guest authors.

Culture becomes the elephant in the room when people do not acknowledge how implicit values shape conflict. “Truth” appears in multiple forms depending on which lenses we are using to view the world. This blog is based on a publication called “Inviting the Elephant into the Room: Culturally Oriented Mediation and Peace Practice”, reflecting insights from the work of UK mediator, Dr Zaza Elsheikh, who places culture and religion at the center of her practice. The blog explores a case from Zaza’s experience and ends with three insights from Zaza’s community mediation, which I believe have useful applications for the peace mediation field, namely regarding power, entry points and mediation success.

A New Angle to Mediation Practice

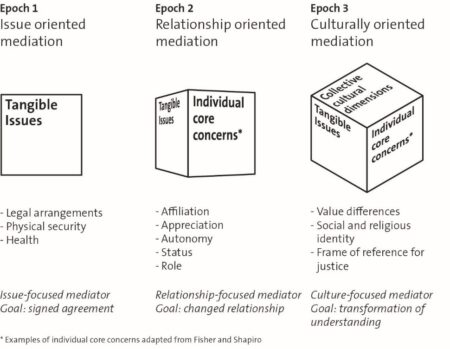

Graphic from Abatis (2021) “Inviting the Elephant into the Room: Culturally Oriented Mediation and Peace Practice”, CSS Mediation Resources

Placing culture in focus in conflict resolution means considering the wider social context in which conflicts manifest as well as the conflict issues and relationships involved. I draw on Cobb, Federman and Castel’s epoch model to situate three overarching schools of conflict resolution, which I associate with “issue”, “relationship” and “culturally” oriented mediation. Culturally oriented mediation builds on other schools of conflict resolution, which address the interests, or deeper motivations underlying why conflict parties say they want something (issue oriented) and repairing the relationship damage caused by conflict (relationship oriented), but also focuses on the third side of the cube (above): the role of collective, cultural dimensions.

The emphasis of Epoch Three conflict resolution, which comes after the September 11 attacks in New York changed the perception of what is knowable. The shadowy presence of a less tangible “enemy” asks us to examine societal discourse in conflict resolution. Subsequently, the conflict resolution practitioner is recognized as part of the conflict system and has greater responsibility to understand social injustices and their own role in this than the classical neutral third party. Where collective cultural dimensions play a substantial role in conflict, I argue that “culturally oriented mediation” is needed.

A Case of Culturally Oriented Mediation

Through an illustration of one of Zaza’s cases in the UK, I will outline some of the features of culturally oriented mediation, although as with mediation in general, there is no blueprint that can be universally applied without adaptation to the context.

A woman called Maryam* approached Zaza to mediate because she was disowned by her family due to her choice of husband (who had been in a previous marriage with her sister). The intensity of emotions bound up with the notion of the shame it had brought on the family led to the threat of murder if Maryam were to approach them. Although Maryam’s brother invoked Islamic morality to bolster his judgement, Zaza identified that there is no taboo applied to this situation under Islam. These feelings instead stemmed from a cultural source in which society expects an individual’s will to be subsumed by communal mores. Classical mediation does not commonly engage with these kinds of worldviews. The legal system of the UK sometimes punishes the tragic results of this kind of shame-triggered violence but does not engage with its source.

Zaza took Maryam’s mandate and turned up at the doorstep of the family unannounced. She overturned conventions in entering the private space of a conflict party, rather than using a “neutral” mediation venue. Classical mediation definitions rely on getting a clear mandate from both parties before attempting mediation. Zaza leveraged the surprise of the situation for an entry point as well as acting in part as representative for the silenced voice (Maryam’s), due to the real threat to her safety. With no other motivation than desiring peace (she was not paid), Zaza instead built trust by allowing Maryam’s brother to vent and rail against his sister, showing that she was there to listen. Listening skills are central to all understandings of mediation, but taking time is important. She did not ignore the tangible issues of safety, nor the dynamics of family relationships, but understood that the cultural components added further complexity to the feelings of rage underpinned by shame. When the time was right and there was enough trust, Zaza directly challenged the leap from the strength of these emotions to the conviction that this justified Maryam’s punishment. She pointed out that in Islam, people are solely accountable to God and Maryam’s brother broke down in tears. Zaza also mentioned the legal consequences of a life in prison, while he had children to care for.

Mediation is always practiced within the confines of the legal system and these checks on reality are important when working between different cultures that have varied frames of reference for justice. Zaza explores taboos that would normally not feature in mediation processes and uses non-judgmental questions to discover what beliefs underlie them. It is important that legal boundaries are discussed explicitly in cases such as these.

The mediation ended without a formal agreement, but Zaza built trust to the extent that she is still in contact with the family more than seventeen years later, who send her cards and photos on holidays that she understands are meant for Maryam. Success in culturally oriented mediation cannot be measured only by formal agreements, but Zaza saw success in this case as building understanding so that Maryam is safe from harm.

Insights from a Culturally Oriented Approach

Zaza’s work is grounded in her extensive community-based mediation, and while there are different scope conditions for political conflicts, some of the lessons that apply to peace mediation are as follows:

1. Understand Power and Positionality

From the outset, it is important to include a culturally sensitive approach to conflict analysis, understanding factors that could be exacerbating conflict when different worldviews are involved and reflecting upon how the identities of the mediation team are situated within these dynamics. International mediation institutions could be more reflective and upfront about the cultural values they represent when engaging in mediation.

Sticking to a strict code of professional distance, means the mediator can miss the elements that allow them to connect from one human to another. By entering the family’s private space, Zaza showed she took an interest in their lives. This can be achieved in peace mediation, e.g. in the Mozambique negotiations where the mediators went into the bush to meet one of the conflict parties rather than inviting them to a meeting room in a hotel.

2. Use Entry Points Across Cultural Difference

It is not easy to facilitate an exchange where people see the world in vastly different ways. In her community mediation work, Zaza recognizes that where worldviews are involved, a long trust-building phase and extended follow-up work is needed. Peace mediation would also benefit from longer pre- and post- mediation phases which are properly funded. These activities would look different depending on the context and people involved.

Peace processes could benefit from more inventiveness. Zaza uses “respectful persistence”, not taking the first rejection as a sign to stop engaging. While it is harder for a state actor to work without a mandate from both parties than in the community case presented here, other entry points that do not rely on mediation alone could be leveraged to build trust. Non-governmental organizations have greater agility in this respect and may benefit from more enhanced support for non-traditional ways of engaging.

3. Widen the Measure of Success

When mediation reaches a transformation or agreement stage, the symbolic act to mark this should correspond to something meaningful to the conflict parties, embedded in their own cultural context. For example, international mediation may not always need to place so much emphasis on signing a peace agreement or on monitoring and evaluation methods that do not allow flexibility. A signature or press photo moment may not have emotional resonance outside of specific circles and may not connect with the public at large. At a time when the days of grand bargaining and comprehensive peace agreements are becoming relics of the past, there is an opportunity to look for new ways to imbue closure of a process with cultural significance and to celebrate events that represent smaller steps to peace.

Community mediators often confront issues within family systems or groups that connect to the wider politics of their national context, and by default to global issues. Zaza’s work reflects this by its embeddedness in a UK legal and cultural system, the wider dynamics of growing national polarization shaping the context and global discussions of migration and addressing difference in society. Peace mediation could benefit from exploring further insights from innovative practitioners, who are not afraid of addressing cultural differences in their work.

* Maryam is an assumed name to protect the identity of the person involved.