Image courtesy of Morning Brew/Unsplash.

This blog belongs to the CSS’ coronavirus blog series, which forms a part of the center’s analysis of the security policy implications of the coronavirus crisis. See the CSS special theme page on the coronavirus for more.

Stories exert power by constructing one way of understanding the world and by effectively communicating that “reality” to others. Conflict actors understand this when they seek to define the terms in which a conflict takes place, representing themselves as morally sound and the other side as illegitimate.

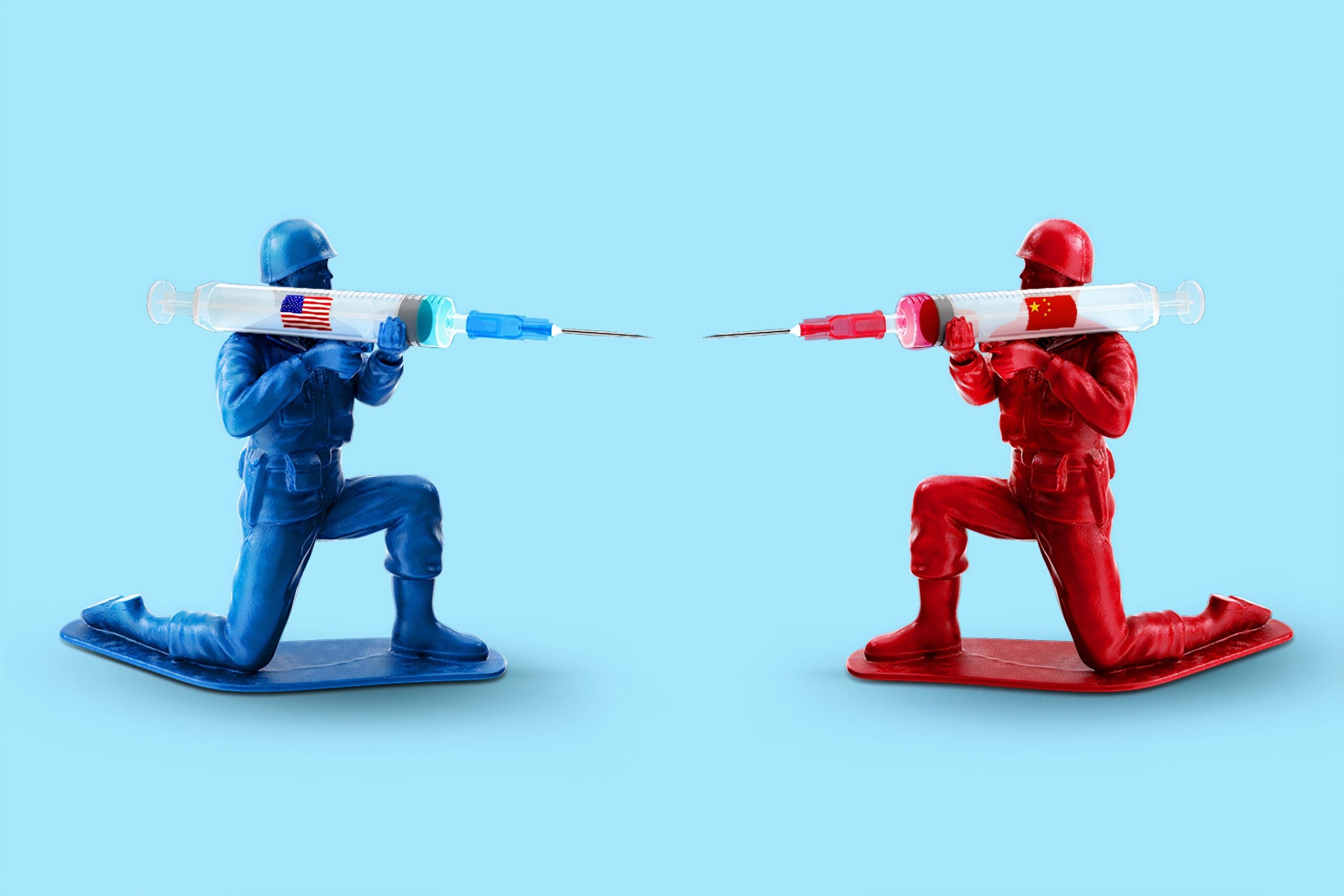

Building on the work of narrative mediator Sara Cobb, we analyze how the respective governments of the US and China have depicted the origins and the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic as the fault of the other side. In recent months, COVID-19 has become central to the US and China’s creation of “master narratives”. Master narratives hugely simplify the plot and characters, contain moral judgments, and form the basis for the generation and perpetuation of a conflict tale. This serves both governments in deflecting criticism away from their domestic responsibilities. Tensions have escalated between the two world powers as a result.

Understanding the narrative dynamics at play in conflict is essential for conflict resolution. One method for transforming the conflict between the US and China consists of analyzing narrative dynamics and supporting the creation of alternative storylines. The latter can break the cycle of escalation by attributing legitimacy to the other side, while also acknowledging the illegitimacy on their own side in contributing to the problem. This involves the politically challenging task of creating spaces where people can voice diverse points of view.

Narrative Escalation

China and the US are in a spiral of escalation that started before COVID-19 with competition for international trade, military control over strategic territories, human rights issues, and the global lead in data-gathering technologies and artificial intelligence.

However, in both countries, domestic pressures related to the handling of the pandemic have brought a new dimension of escalation and entrenched the merits and disadvantages of each political system, with a central collectivist governance set against a liberal decentralized one. Differing styles of governance have resulted in contrasting responses to the pandemic from an authoritarian lockdown, using powers of the state to impose greater surveillance to a lackadaisical president delegating to the individual state level while ignoring the severity of the problem. Whether it is highlighting the cruelty of silencing dissent or the selfishness of rampant individualism, the battle of storylines played out by the two world powers tends to obliterate accounts that do not fit into the master narrative.

In March 2020, Lijian Zhao, a spokesperson of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, insinuated that a US army delegation might have brought COVID-19 to Wuhan. Soon thereafter, the Chinese government adopted the theory that US citizens planted the virus in Wuhan. In early May, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed that the virus had originated in a laboratory in Wuhan without clearly ruling out the possibility that it could be manmade.

These empirically shaky accounts illustrate the dynamics of conflict narratives produced and reproduced in conversations, political speeches, and media reports. From initial criticism of the Chinese authorities for having obscured information on the outbreak of the pandemic, and scrutiny of the US government for having failed to impose effective measures that would have prevented the virus from spreading, these narratives have become increasingly regressive, building up to a negative climax. The storytellers have created a linear plot that situates events in a simplified context, ascribing the responsibility for the negative outcome to the other side.

US Narratives

Narratives become “radicalized” when parties start blaming and denigrating the other side to escape responsibility. As domestic criticism for failing to contain the pandemic in the US started to grow in April 2020, President Donald Trump turned to attacking the Chinese government for the way they dealt with the crisis. Trump’s desire to deflect from his own responsibility was obvious when he responded to a critical question in a press conference by saying: “Don’t ask me, ask China.”

Radicalized narratives, such as the one advanced by the US government when it speaks of the “China problem” and the “Chinese virus”, affect intra-group dynamics. These narratives limit what can be said in the public sphere and prevent other voices from making the storyline more complex again. Sara Cobb calls the silence of deviations from the dominating story “narrative policing”. In the US context, this dynamic of silencing is at play in the electoral debate. In early May, the Trump campaign started running an ad attacking the Democratic candidate, Joe Biden, for being soft on China. Hinting at malign intentions of the Chinese government behind COVID-19, the ad states: “China is killing our jobs and now killing our people.” In response, the Biden campaign also started running xenophobic ads fomenting anti-Chinese sentiments in ways that angered many Asian-Americans. This highlights how radicalized storylines create spirals of silence that erode nuances in public discourse.

This is not to suggest that there are no dissenting voices in the US. Many Americans have criticized the way Trump has handled the pandemic. In spite of calls to release inmates, the US prison system has been overwhelmed with COVID-19 infections and deaths. Even staunch Republicans have been alarmed by the health risks caused by the failure to take the issue seriously. However, Trump never allows this to infiltrate his master state narrative, which casts his response as legitimate, upholding individual freedoms and the model of federalism (and blaming individual state governments when things go wrong), while framing China as illegitimate for its repression of citizens. Pompeo’s speeches have stressed the extreme differences between the political systems, stating that “today China is increasingly authoritarian at home and more aggressive in its hostility to freedom everywhere else” as justification for rejecting open dialog between the two countries.

Chinese Narratives

The Chinese government has been investing in news journalism across Europe and North America for some time and understands the need to control its own narrative, both for domestic reasons and to promote its image on the world stage as a great power. Xi Jinping has published his speeches and essays in books and had them translated into different languages. China Global Television Network has also hired Western journalists to “tell China’s story well.”

In the course of the recent escalation, Chinese diplomats have become vocal on social media and blogs denouncing, for instance, the “West’s” inability to deal with the virus because of endemic individualism. Moreover, New China TV launched a video with Lego figures mocking US attempts to blame China for COVID-19 and its spread.

Nevertheless, the Chinese government dismissed the initial warnings of doctors like Li Wenliang, who had alerted them to the dangers of the virus. They have used the state of emergency imposed in response to the pandemic as a pretext to silence dissenting voices, such as Xu Zhangrun, an academic briefly imprisoned on spurious charges after publishing an essay criticizing the government’s pandemic response. Repression against the Chinese Muslim minority has intensified, with Uighurs in detention camps quarantined without warning and then forced back to work in factories. In the case of Li Wenliang, public sympathy of Chinese citizens towards his fate gave rise to criticism of the Communist Party of China (CPC), leading it to shut down expressions of solidarity as soon as they surfaced by deleting unfavorable Weibo (Chinese social media) comments. Recently, China has also enforced new security laws in Hong Kong to stifle protests.

The Chinese government seeks to portray itself as a responsible actor that plays an important role in the World Health Organization (WHO). The Foreign Ministry has been quick to point out the WHO’s praise for China’s coordinated response to the virus in its public communications. Projects such as the building of a hospital in ten days were accompanied by a public livestream, and Western criticism of China’s authoritarian regime has been juxtaposed with stories of how countries around the world have “followed China’s lead.” These accounts are part of a narrative constructing China as an ideological alternative to a US political model in a state of decline.

Crafting Better Narratives

Sara Cobb argues in favor of transforming simplified and regressive plots into more complex or “better-formed stories”, as this can re-open the space for imagining peaceful futures. In a better-formed story, the plot becomes more complex. Rather than merely depicting the other side as creating the problem, a better-formed story highlights how multiple actors contribute to the conflict. A narrative lens opens up possibilities for dialog, negotiation, and mediation. Peace practitioners can support the crafting of such better-formed stories by encouraging all sides in a conflict to recognize their own legitimate grievances and actions while also acknowledging how they have contributed to the conflict and the deterioration of the relationship. This requires an analysis of how positions and interests are embedded in wider narratives.

With the US and China, for example, this could mean that both countries would have to recognize their own responsibility in contributing to the spread of the pandemic, which is one part of the larger geopolitical conflict narrative. Addressing this could begin to disrupt the repetitive patterns of accusations and counteraccusations and lead to new understandings of the past and the present while providing the basis for all parties to envision and build peaceful futures.

US and Chinese societies need to explore possibilities for crafting better-formed narratives that at least partly acknowledge domestic criticism. This entails collaboration between, for instance, scientists, engineers, journalists, artists, novelists, and business actors across both countries to discuss common global and domestic problems, such as emerging digital technologies, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic. A lasting solution would also have to include processes for keeping track of the evolving narrative dynamics and addressing radicalized narratives when they re-surface.

About the authors

Katrina Abatis is a program officer in the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

Emanuel Schäublin is a senior program officer in the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.

One reply on “Infectious Narratives: US, China, and COVID-19”

Fabulous perspective. We need to unpack and mainstream this thinking more. China and USA could be global partners for peace which would transform the many smaller conflicts they are both stakeholders in. Blame and over simplification in 2020 is out of date. Thanks to the authors for taking time to open up this issue.