This article was originally published by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) on 28 August 2017.

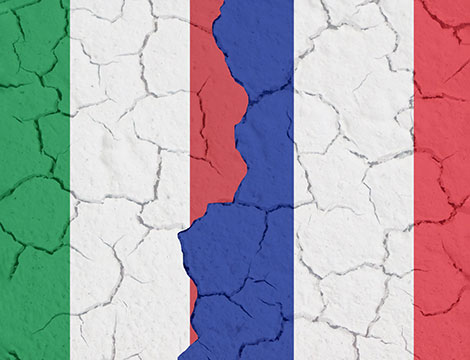

The leaders of France, Italy, Spain and Germany met in Paris on 28 August for a summit hosted by President Emmanuel Macron in the latest indication of France’s efforts to assume a key leadership role in the post-Brexit EU. Yet, the event is also an occasion for the French president to smooth ruffled feathers among EU partners, particularly in Rome, after a series of diplomatic spats led to a plummeting of relations and the resurrection of old grievances between the two countries. A second, and arguably more important bilateral summit between France and Italy is also scheduled for 27 September in Lyon, another indication of the need to patch up relations and promote an outward image of cooperation between the two EU neighbours.

Tensions between France and Italy soared in July following the French government’s decision to nationalise shipbuilder Stx/Chantier de l’Atlantique rather than give Italy’s Fincantieri a majority stake, thus reneging on an agreement between Italy and France’s previous government. Diplomatic relations had already been tested earlier that week when President Macron organised a peace conference on Libya without inviting the Italian government that considers itself a key player on the Libyan dossier. The two events, which are unrelated, created a perfect storm among Italians, resulting in some public spats and a queue of French ministers flying to Rome to patch up relations. Joint declarations and photo ops have not healed the wound, however, and tensions persist.