أنقرة ــ في الأسبوع الماضي، صَعَّد رئيس الوزراء التركي رجب طيب إردوغان من حِدة استجابة حكومته لتحقيقات الفساد التي أرقت البلاد منذ ديسمبر/كانون الأول بإعادة هيكلة قيادات السلطة القضائية والشرطة. ولكن من الخطأ أن ننظر إلى هذا باعتباره معركة بين السلطتين التنفيذية

والقضائية، أو محاولة للتغطية على الاتهامات التي أدت إلى استقالة ثلاثة وزراء. فالقضية هنا تدور حول استقلال سلطات إنفاذ القانون وحيدتها. والواقع أنه في وسط اتهامات بشأن أدلة ملفقة يقول إردوغان الآن إنه لا يعارض إعادة محاكمة كبار الضباط العسكريين المدانين بالتخطيط للإطاحة بحكومته.

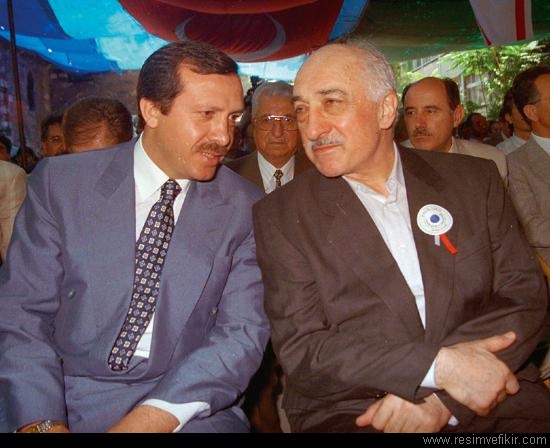

وتعكس التطورات الأخيرة إلى اتساع هوة الخلاف بين حكمة إردوغان وحركة جولِن بقيادة فتح الله جولِن، وهو الواعظ الإسلامي الذي يقيم حالياً في المنفى باختياره في مدينة بالقرب من فيلادلفيا في الولايات المتحدة. كانت حركة جولِن من الكيانات المهمة الداعمة لحزب العدالة والتنمية الحاكم وجهوده الرامية إلى ترسيخ السيطرة المدنية على المؤسسة العسكرية خلال أول ولايتين لحزب العدالة والتنمية في السلطة. ولكن يبدو أن الحركة تخطط الآن لانقلاب على السلطة.

والواقع أن العديد من أعضاء السلطة القضائية والشرطة المرتبطين بموجة اتهامات الفساد الموجهة إلى مسؤولين حكوميين ورجال أعمال وأفراد من أسر الساسة متصلين بحركة جولِن. وما بدأ بوصفه تحقيقاً في اتهامات مزعومة بالكسب غير المشروع سرعان ما تحول إلى حملة تشويه تدعمها المعارضة.

وتثير صراعات تركيا الحالية العديد من التساؤلات المهمة حول العلاقة اللائقة بين البيروقراطيين والمسؤولين المنتخبين في الديمقراطية التعددية. وسوف تتطلب الإجابة على هذه التساؤلات مناقشة تتجاوز قضايا مثل الفصل بين السلطات واستقلال القضاء وتشرح العلاقة اللائقة بين السياسة والدين. وهنا يشكل التوصل إلى فهم واضح للسياق التاريخي للأزمة الحالية أهمية حاسمة.

عندما أصبحت تركيا دولة ديمقراطية في عام 1950، حاولت النخب الكمالية العلمانية المنتمية إلى النظام السابق تسخير قوة المؤسسة العسكرية والبيروقراطية الحكومية للسيطرة على الحكومة المنتخبة. والواقع أن المؤسسة العسكرية التركية، بدعم من السلطة القضائية، تدخلت بشكل واضح في عمل الحكومة المدنية في أعوام 1960، و1971، و1980، و1997، وفي كل مرة باسم حماية العلمانية.

وفي الرد على ذلك حَرِصَت جماعات دينية مختلفة، بما في ذلك حركة جولِن، على تشجيع أتباعها على تولي مناصب في الجهاز البيروقراطي للدولة والمؤسسة العسكرية. وفي تسعينيات القرن العشرين ردت الحكومات العلمانية المدعومة من قِبَل المؤسسة العسكرية الضربات فحاولت تطهير البيروقراطيين والقادة العسكريين المتدينين: فكان من لا يتعاطى الكحول أو لا ترتدي الإناث من أفراد أسرته الحجاب يصبح على الفور موضع اشتباه.

ومع تطبيع الديمقراطية التركية في أعقاب فوز حزب العدالة والتنمية في عام 2002، أزيلت القيود المفروضة على تجنيد وتوظيف وترقية المواطنين المتدينين في المراتب العليا من الجهاز البيروقراطي ــ وهي العملية التي أفادت بشكل خاص أعضاء حركة جولِن، التي كانت تتمتع بشبكات تعليمية وإعلامية وتجارية واسعة. وبدا أتباع جولِن ــ الذين زعموا أنهم يدعمون الديمقراطية الليبرالية والشكل السمح الحديث من الإسلام الذي يتبناه حزب العدالة والتنمية ــ وكأنهم الحلفاء الطبيعيين لحكومة إردوغان.

ولمدة عشر سنوات، لعبت الشركات المتصلة بحركة جولِن دوراً معترفاً به على نطاق واسع ــ ومحل تقدير ــ في النمو الاقتصادي والتنمية في تركيا، في حين دربت المدارس التابعة لحركة جولِن الطلاب على العمل في وظائف الخدمة العامة. وطالما كانت شروط توظيف وترقية البيروقراطيين تستند إلى الجدارة، فإن حزب العدالة والتنمية لم يجد مشكلة في قبول التمثيل المفرط لأتباع حركة جولِن في فروع بعينها من الحكومة.

وكان قبول حركة جولِن نابعاً من اعتقاد مفاده أن أعضاء الحركة سوف يلتزمون بشرط أساسي في الديمقراطية التعددية مفاده أن البيروقراطيين ــ سواء كانوا من المسلمين في تركيا، أو المورمون في الولايات المتحدة، أو البوذيين في اليابان ــ لا يسمحون لمعتقداتهم الدينية بإفساد التزامهم بالخدمة العامة وسيادة القانون. وما لم تتخيله الحكومة هو أن رؤية جديدة للوصاية البيروقراطية على الحكومة المدنية قد تنشأ.

وبرغم أن أتباع جولِن اختلفوا مع العديد من سياسات الحكومة، فإنهم كانوا إلى حد كبير يدعمون حزب العدالة والتنمية في الانتخابات الثلاثة الأخيرة. وكان الجدال السياسي حول إعادة هيكلة “المدارس الخاصة الباهظة التكاليف التي تؤهل طلاب الدراسة الثانوية لاجتياز امتحانات القبول بالتعليم الجامعي” هي ما دفعهم إلى رفض الحزب تماما.

تدير حركة جولِن ربع هذه المدارس على الأقل، والتي تشكل عنصراً رئيسياً في شبكة تعليمية تابعة للحركة وتبلغ قيمتها عدة مليارات من الدولارات وتساعدها في تجنيد الأعضاء الجدد. وبالتالي فإن أعضاء الحركة كانوا ينظرون إلى الجدال الدائر حول هذه المدارس باعتباره تحدياً مباشراً لنفوذهم.

ولكن رد فعلهم لم يكن متناسبا ــ خاصة وأن خطط الحكومة لم تكن نهائية. وعلاوة على ذلك، لم يكن الاقتراح متعلقاً بحركة جولِن؛ بل كان استجابة لشكاوى المواطنين بشأن الاضطرار إلى دفع رسوم باهظة لإعداد أطفالهم للالتحاق بالجامعات العامة المجانية. ولم تؤخذ حركة جولِن على حين غرة؛ فقد انخرط ممثلو هذه المدارس في حوار مع المسؤولين في وزارة التعليم لبعض الوقت.

وكما هي الحال في أي نظام ديمقراطي، فإن الانتقادات العامة لسياسات الحكومة التركية أمر طبيعي وصحي. ولكن المحاولات التي بذلها أعضاء السلك القضائي والشرطة المنحازين لحركة جولِن لابتزاز وتهديد الحكومة ومساومتها بشكل غير قانوني غير مقبولة.

والآن الأمر متروك للمحاكم لكي تستشف الحقيقة بشأن الفساد بين “الموظفين العموميين” في تركيا. ولكن كل الدلائل تشير إلى حملة سياسية منسقة من جانب أتباع جولِن، بما في ذلك كبار مدعي العموم المتورطين في قضايا الفساد الأخيرة ووسائل الأعلام الموالية لحركة جولِن التي دافعت باستماتة عن نزاهة مدعي العموم (برغم المخالفات العديدة ــ مثل عمليات التنصت المكثفة غير المرخصة قانونا ــ والتي تم الكشف عنها). فضلاً عن ذلك فإن مجموعة منسقة داخل السلطة القضائية يشتبه في إقدامها على زرع أدلة زائفة ــ وهي الادعاءات التي أدت إلى الدعوات المطالبة بإعادة محاكمة أفراد في المؤسسة العسكرية.

وهذا لا يعني بكل تأكيد أنه لم تكن هناك محاولات انقلابية من قِبَل أفراد في المؤسسة العسكرية في الماضي أو قضايا خاصة بجرائم فساد ارتكبها ساسة وبيروقراطيين. الأمر المهم هنا هو أن تركيا تحتاج إلى إصلاحات قضائية تفضي إلى إزالة احتمال نشوء عصابات منظمة تستغل سلطاتها الدستورية لتحقيق أهدافها ومصالحها الضيقة.

وهذا خط أحمر بالنسبة لأي نظام ديمقراطي. فلابد أن يتمتع المواطنون الأفراد بالحرية في الحياة وفقاً لمعتقداتهم؛ ولكن لا ينبغي أن يُسمَح لرؤية عَقَدية غير خاضعة للمساءلة بتشكيل سلوكهم كموظفين مدنيين وبيروقراطيين.

وفي عموم الأمر، لابد أن يكون الجدال بشأن حركة جولِن بمثابة فرصة لتوضيح العلاقة بين الدين والسياسة، في حين يعمل على تذكير عامة الناس في تركيا ــ والبلدان ذات الأغلبية المسلمة في مختلف أنحاء المنطقة ــ بالقيم الديمقراطية الأساسية التي مكنت تركيا من التطور والازدهار.

ترجمة: أمين علي Translated by: Amin Ali

.Copyright Project Syndicate

إرتان آيدين كبير مستشاري رئيس الوزراء التركي رجب طيب إردوغان.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Überdehnt sich die Bewegung von Fethullah Gülen?

Turkey: Has the AKP Ended Its Winning Streak?

Turkey’s “Super Election Year” 2014: Winner Still Takes All?

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.