In a blog I wrote for OSINTblog.org the other week I discussed the intelligence community’s preoccupation with Islamist political extremism. This preoccupation, I argued, is a manifestation of an obsession with global Jihad in academic discourse and open source intelligence (OSINT) gathering. I argued that, in the former case, this hampers academic progress and, in the latter, undermines security.

When intelligentsia and intelligence services speak of “terrorism,” it often carries the connotation of Islamist political extremism. However, as a couple of scholars with NUPI, an ISN partner, concluded in a report: although figures of speech contribute to the cognitive dimension of meaning by helping us to recognize the equivalence to which we are committed, cognitive shortcuts or ‘heuristics’, raise problems and do little to increase our understanding of terrorism as a phenomenon. In fact, cognitive shortcuts are counterproductive of why we study terrorism, namely, to enhance security.

Why is this? First of all, with the bewildering diversity of cultural contexts and world views, employing heuristics frustrates communication at the global level. Second, when we squeeze the discourse on terrorism into a narrative straitjacket we run the risk of failing to connect knowledge of one type of terrorism with knowledge of another. Finally, we open the floodgates for prejudices.

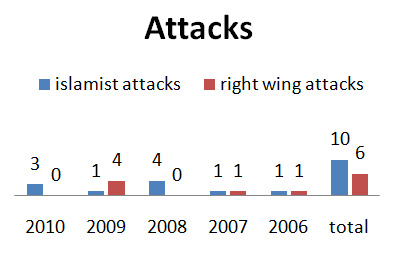

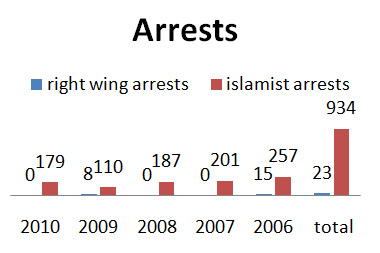

The argument made by the NUPI scholars complements some interesting data from Europol’s five most recent “EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Reports.” These reports testify to the great disparity in the resources devoted to combating right wing extremism, as opposed to Islamism, even though the number of terror attacks is relatively similar (see charts).

Much of the feedback I received agreed that the fissure can be partly explained by the fact that our threat perception from Islamist groups is substantially higher than from right wing groups. But the feedback also concurred in the insufficiency of this explanation. One interesting point is that right wing groups and Islamists have different advertising cultures. Right wing extremists demonstrate, organize parades, and arrange concerts where they play white power music; Islamists, by contrast, tend to broadcast their threats directly on social media.

In the search for an explanation, commentators suggested that the preoccupation with Islamist political extremism is justified because this type of terrorism is more destructive, and therefore deserves the highest amount of resources.

This seems a reasonable claim, but is there anything to it? The problem is that the vast majority of attacks are not Islamist in nature. The latest Europol report shows that in 2010 only three attacks had Islamist connections, while 160 were conducted by separatist groups and 45 by left wing groups. If radical Islamism deserves the most attention, it must be then shown that when Islamists do strike the destructiveness of their attacks compensates for their relative infrequency. But there is no data to support this.

My question, then, is this: when we talk (as we so often still do) as if terrorism were mostly Islamist in nature, origin, or significance, are we still talking about the world we actually live in?

If not, we may be classic examples of what John Steinbrunner and Leon Festinger call ‘cognitive misers’ — which is to say, seekers of cognitive consistency, who categorize, stereotype and simplify causal inferences when processing information about the world. According to Steinbrunner and Festinger, we have a cognitive need to discount inconsistent information (in this case, the small number of terror attacks from Islamists in Europe) and correct discrepancies between new information and pre-established beliefs (in this case, the belief that Islamism poses the greatest threat) to preserve coherence in our belief systems and make sense of the world around us.

The obvious danger of such filters is that they hinder intelligence gathering. Reportedly, the perpetrator of the recent atrocities in Norway had posted suspicious material several times on his social media sites, yet escaped the attention of the Norwegian intelligence services.

Not all filters are bad, however, and without any at all life would become unmanageably complex. Luckily for us, both Steinbrunner and Festinger believed that one of the most effective ways to rid oneself of harmful “filters” is to become aware of them. So let’s do just that.

|

|

|

2 replies on “We Are All Cognitive Misers”

openDemocracy have also just published an article on this topic. It’s written by a Norwegian who was in the US at the time of the shootings, and notes his astounded reaction at how much CNN and FOX were pushing the jihad idea…

http://www.opendemocracy.net/magnus-nome/why-let-facts-ruin-story-norwegian-comments-on-us-coverage-of-norway-terror

[…] here: http://isnblog.ethz.ch/intelligence/we-are-all-cognitive-misers Tweet This was written by Florian Schaurer. Posted on Friday, August 5, 2011, at 16:39. Filed […]