I closed yesterday’s blog by asking: “So, am I right to assume that Hybrid Warfare is (and will be) the new norm in our back-to-the-future world, or are we slowly but surely vanquishing violence?” The very idea that organized violence and its effects are in irreversible decline is absurd to many a self-proclaimed realist, and for at least three reasons. First, there exists and will always remain the pesky problem of human nature. In other words, Immanuel Kant was right; human beings are indeed “crooked timber.” When you kludge other factors to eternally perverse human nature, to include competition for resources, a structurally defective international system, and inevitable political frictions, the idea that war and its noxious effects are on the wane is seemingly absurd. Indeed, as of the autumn of 2011 weren’t there 18 wars of varying intensity occurring around the globe?

Second, realists tend to dismiss or at least underestimate the evolving power of norms (to include the concept of political legitimacy) and human rights. In their minds, these wispy intangibles are largely fair weather phenomenon. They have not, nor will they ever gain decisive power or influence over time. They represent, in short, superstructural fluff, as Karl Marx might have put it. People honor and practice agreed upon norms and rights when they can, but they invariably jettison them when they must. As a result, norms and rights cannot stand up to the biting winds of war, let alone exercise due influence during periods of genuine crisis.

Finally, realists tend to snort about the pending demise of war and its effects because they know all too well that military-industrial-media-government complexes continue to feed the world’s war machines. Indeed, depending on the measurements you use the numbers can be sobering. For example, SIPRI – the respected Swedish think tank – estimated that global military expenditures for 2009 equaled $1.531 trillion – up 49 percent since 2000. The new armaments that are part and parcel of this spending, by the way, are not being produced solely for defensive purposes. Seventy-eight percent of BAE Systems’ military-related products are produced for export, as are 75 percent of Thales and 70 percent of Dassault products, as are 68 percent of the products Saab makes. What these numbers tell us – and they are only the tip of the iceberg – is that that for some nations (in the above cases, Great Britain, France and Sweden) arms exports are intimately tied to national prosperity. When you then go one step further and internationalize the manufacturers of these arms, make them interdependent and finally intertwine their fates, you are right to conclude, or so the realists argue, that the needed technological preconditions that feed into war are holding firm, if not actually growing.

But wait, demands the opposing camp: even if we grant you that human beings are intrinsically violent and that international norms have failed to grow in absolute strength, which we are actually not prepared to do; or that Chinese defense spending did rise at an average of nearly 10 percent per year between 1990 and 2005, while India’s rose a total of 37 percent between 2000 and 2007; or that comparatively high increases in spending occurred in Singapore and South Korea as well, just how representative are these developments? Are they illustrative of a broader system-wide march towards greater militarism, and therefore a higher probability of organized carnage in the future? According to Steven Pinker and like-minded thinkers, the answer is “no.” (See Pinker’s recently released The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined; his 19-minute TED Video – Steve Pinker on the Myth of Violence – which you can find here, and his personal FiveBooks selections here.)

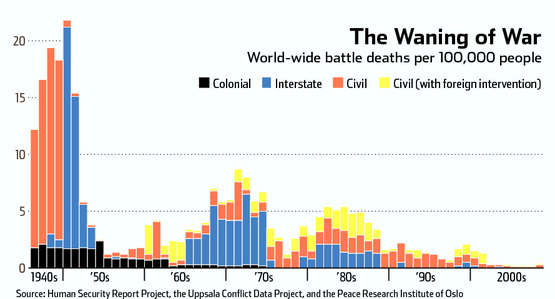

As mentioned earlier in this blog series, the political utility of hard power, particularly when applied via conventional military means, has decreased. Indeed, this now significant mismatch between traditional means and desired ends has meant that wars have become less common and far less lethal than in the past, as the following chart shows.

|

What the chart doesn’t tell us, according to Pinker, is that even if we take into account the total nature of the 20th century’s world wars, genocides, ethnic cleansing campaigns, and war-related diseases and famines, a conservative estimate puts deaths from these human causes at just three percent of the deaths in the 20th century. In contrast, in prehistoric hunter- gather societies roughly 15 percent of people came to violent ends. Clearly, argues Pinker and his fellow travellers, a civilizing process has and continues to occur in war – in its frequency, character and conduct.

Finally, why has this civilizing process occurred and continues to get stronger? Well, according to assorted anti-war progressives some of the reasons are as follows.

- The pacifying effects of economic exchange, interpenetration and mutual interest.

- The historical growth of the state, with its traditional monopoly on violence and its ability to curb its use through alternative means, to include the administration of justice.

- The demise of communism, which ended the proxy wars that were part of the superpower competition in the developing world.

- The changing nature of warfare. (Not many of today’s conflicts involve interventions by major powers, or feature prolonged engagements between large conventional armies equipped with heavy mechanized forces.) In fact . .

- The low-intensity insurgencies of the 1990s onwards have been almost always intra-state affairs. In turn, the irregular forces that typically fight them are small, ill-trained, mostly equipped with small arms and/or light weapons, and not eager to fight overt battles.

- Wars have become truly localized (due to the two previous developments).

- Major increases in the scope and effectiveness of humanitarian assistance to vulnerable populations in war-torn areas.

- The increased use of international peacekeeping forces, which have broadly managed to keep the peace, even if only tenuously.

- A cascade of “rights revolutions,” to include the rise and wide acceptance of the idea that personal well-being and freedom from suffering are important social values in and of themselves.

- Rising cosmopolitanism – e.g., the expansion of people’s provincial worlds through literacy, mobility, education, science, history, journalism and mass media.

- New technologies that have powered an expansion of rationality and objectivity in human affairs. Indeed, people are now less likely to privilege their private interests automatically over a more general good.

- The feminization of political and general culture, which has deflated the values of warrior castes.

The above 12 reasons, working both singly and in groups, are why the average conflict in the new millennium has killed 90 percent fewer people each year than did the average conflict in the 1950s. The 12 reasons also help explain why so many people now see organized violence as intrinsically illegitimate, abnormal and unnecessary; why recent war memorials tend to lament past sacrifices rather than celebrate past glories; and why more and more people have come to realize that war is a human construct. It is not, in other words, synonymous with fate; it is not a blind force of nature that we must passively endure; and it is not by definition eternal. Instead, it is a learned behavior that we can collectively unlearn. We can, in short, supplant it and make it obsolete. However, getting to perpetual peace may require us to work through and ultimately wash our hands of Hybrid Warfare. Fair enough, but the assumptions and beliefs we will bring to this task are totally different from those we investigated at the very beginning of this eight-part series. We have indeed made progress.