Despite playing second string to the South China Sea disputes in recent years, the state of Sabah (also known as North Borneo) has long been a major irritant in bilateral relations between the Philippines and Malaysia. However, a lasting resolution of this longstanding issue would help cement bilateral ties between the two countries, enhance maritime security and help regulate seaborne trade. Finally, a resolution may help determine the fate of thousands of Filipino refugees, migrants and their descendants in Sabah, many of whom remain stateless to this day.

Roots of Contention

The Sultanate of Sulu obtained Sabah from Brunei after helping it to quell a local rebellion. In 1761, the Sulu Sultan entered into an agreement with the British East India Company to set up a trading post on Balenkong Island. This was followed in 1878 by the signing of an agreement to lease the sultan’s dominions in North Borneo in return for rent from the British North Borneo Company. After 1946, the payment of the annual lease passed from the British to the Malaysian government and continues to this day. When Sabah was transferred from the British North Borneo Company to the Crown under the 1946 North Borneo Cession Order, former US Governor-General and then foreign affairs adviser to the newly established Philippine Republic Francis Burton Harrison labelled the transfer as illegal on the basis that other concerned parties were not consulted. In 1963, then-Philippine President Diosdado Macapagal refused to recognize the Federation of Malaysia because of the inclusion of Sabah.

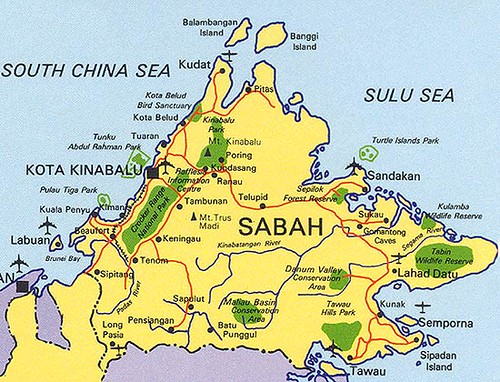

As the ‘rightful heirs’ to the sultanate, the Philippines continues to stake its claims over Sabah, albeit with less enthusiasm than in the past. For instance, in 2001, Manila declared itself an interested party in negotiations between Indonesia and Malaysia over the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands. As these are located off Sabah, the Philippines argued that the decision of the International Court of Justice over the status of the islands may have a bearing on its territorial claims.

Tension Returns

The ghosts of the Sabah issue resurfaced again recently after a violent standoff between loyal followers of the Sultan of Sulu and Malaysian troops in Tanduao village, Lahad Batu. There was also a similar encounter in Simunul village in Semporna, raising fears that the conflict may spread over to other areas of northern Borneo. The timing of the standoff prompted speculation that parties opposed to the Malaysian-brokered peace deal between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) were behind the staging of the drama. Some Philippine senatorial candidates, possibly in order to enhance their nationalist credentials, have also used the incident to lobby Manila into reviving its claims on Sabah. However, Malaysia’s contribution to the peace deal with the MILF suggests that the Aquino government may not take their demands too seriously.

Caught in Limbo

The recent unrest in Sabah has also reignited interest in the fate of the state’s Filipino community. Whether they are refugees, economic migrants or illegal immigrants, Filipinos tend to be lumped into one group and subjected to many negative stereotypes and prejudices. Many Malaysians claim, for example, that ethnic Filipinos put a strain on social services, take jobs away from locals and generally pose a security threat. Many refugees also remain stateless and their local status remains precarious. As a result, many have also been subjected to abuse or discrimination, despite the fact that some are born and raised in Sabah. In addition, many undocumented Filipinos have also been trafficked to Sabah through the porous Philippines’ southern backdoor to work in palm oil plantations. Some have even been forced into prostitution. The plight of these Filipinos has enraged many of their relatives and kinsmen on the other side of the Sea of Sulu. However, the Philippines’ continued reluctance to set up a consulate in Sabah, on account of its outstanding claim, means that the fate of many of these Filipinos remains in limbo.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is an MA Asian Studies student at the University of the Philippines. His areas of interest include territorial and maritime disputes, Philippines-China and China-ASEAN relations, and energy security. He can be reached at lucioatacup@rocketmail.com

For related content please see:

Malaysia’s Coming Election: Beyond Communalism?

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s featured editorial content and Security Watch.