This article was originally published by E-International Relations on 3 December 2016.

Britain’s decision to leave the EU has been labelled an ‘exceptional act of self-harm’. But is it? In October South Africa became the first country to announce its formal withdrawal from the International Criminal Court (ICC). This was soon followed by the exit of Burundi and Gambia and by Russia’s announcement that it intends to withdraw from the Rome Statute which establishes the ICC. Although the Court has been hampered since its inception by the refusal of major states such as the US, China and Russia to submit to its jurisdiction, these withdrawals represent an unprecedented challenge to its legitimacy. Things look no brighter in the area of international security cooperation, as illustrated by the slow acceptance of Additional Protocol safeguards under the NPT and the failure of Annex 2 countries to ratify the Comprehensive Treat Ban Treaty. Even longstanding alliances seem at risk of unravelling. In June Uzbekistan announced its (re-)exit from the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and NATO leaders are growing increasingly nervous that the Trump Administration will turn its back on America’s allies. Meanwhile, there is a growing trend towards withdrawal from and denunciation of international human rights treaties, the G8 has shrunk to the G7, and the use of UNSC vetoes—which were at a historic low during the 1990s—is once again on the rise.

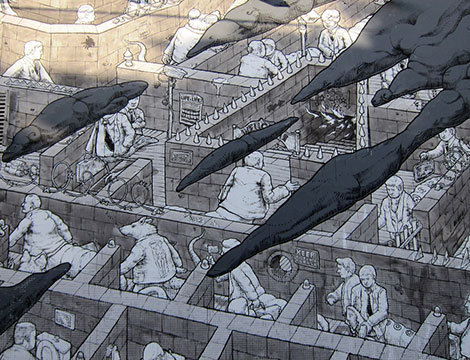

When viewed against the backdrop of these multiple failures of multilateral cooperation, Britain’s decision to leave the EU appears far from exceptional. Rather, it appears as merely another manifestation of the broader crisis affecting global multilateral institutions. This crisis has many manifestations; fewer multilateral treaties are being signed and ratified, the implementation of existing treaties is poor and states are increasingly rejecting oversight of treaty obligations and monitoring of compliance by multilateral organizations (MOs). Thus, if the second half of the 20th century was the age of integration—of nations coming together and pooling sovereignty in pursuit of common goals—the 21st century looks increasingly as an age of drifting apart.

What is causing this global turn against multilateralism? Some observers point to increased polarity and fragmentation in world politics: the growing East/West divide, an America that oscillates between unbridled unilateralism and strategic retrenchment, and an increasingly assertive China. Another argument points to the fact that many organizations are failing to deliver on their declared goals. The G7 has failed to promote economic recovery among euro-zone countries, the WTO has failed for decades to conclude negotiations of the Doha Development Agenda, the UN has failed to promote regional peace and stability, and the NPT has failed to stem nuclear proliferation. Thus, insofar as commitments to multilateralism depend on ‘output legitimacy’—the notion that MOs enable states to achieve collective goals that they could not have reached alone—too few MOs currently make the grade.

Equally strong criticism has been raised against current multilateral practices on input legitimacy grounds, with critics charging that the processes through which major MOs reach decisions are non-transparent, unrepresentative, and lacking in democratic accountability and input.

Present multilateral institutions may be short on both input and output legitimacy, but to understand the current crisis of multilateralism, it is necessary also to consider the basic principles, norms and values of multilateralism as an institutional form. As John Ruggie observed decades ago, multilateralism in its pure form is highly demanding. First, multilateralism coordinates relations among states based on “indivisibility” and “generalized principles of conduct”. That is, all states must abide by the same rules. Second, multilateralism entails expectations of “diffuse reciprocity”, meaning that cooperation is “expected by members to yield a rough equivalence of benefits in the aggregate and over time”. In other words, participating states will be winners and losers in turn. However, many global MOs seem to have created permanent winners and losers. The ICC’s perceived ‘African bias’, the WTO’s failure to promote growth in the world’s poorest countries, the World Bank’s failure to eradicate global poverty and the enduring nuclear hierarchy among NPT members—these realities are difficult to reconcile with notions of indivisibility and diffuse reciprocity. Thus, while powerful states are increasingly unwilling to be constrained by MOs, smaller and poorer states are growing increasingly discontented with what they see as the institutionalization of global inequality and discrimination.

It’s also worth noting that—whilst many MOs are failing to deliver desired results—the practice of multilateralism has grown evermore demanding. As many scholars have recognized, whereas multilateral institutions previously provided a framework for ‘institutionalized collective action among states’ whenever a ‘pre-existing consensus existed to deal with common problems’, the 21st century heralded a new era of multilateralism characterized by growing legalization of international agreements and stronger obligations on states to act collectively and submit to the jurisdiction of internal courts and dispute resolution bodies. For some states this has proved too demanding, causing them to retreat from international legal commitments to avoid intrusive monitoring and potential sanctions for noncompliance.

What does this tell us about Brexit? The system-wide crisis of multilateralism suggests that Britain’s retreat from the EU is far from exceptional. What is exceptional about Brexit is that it concerns Europe. In Europe, some claim, “multilateralism has come to be seen ‘as a way of life’—a tried and tested way in which European states have put conflict behind them”. This view has been espoused by A.J.R. Groom who argued that “despite multiple institutional crises…the idea of ‘multilateralism under challenge’ is rather alien to Europe”. Yet, the EU suffers from similar weaknesses as other MOs. Despite a notional commitment to principles of diffuse reciprocity and ‘solidarity’, ‘economic mobility’ among EU member states has been relatively low. Since joining the European Communities in the 1980s, GDP per capita in Spain, Portugal and Greece has remained vastly lower than in France and Germany. The 2004 Eastern enlargement has also so far produced limited economic convergence. In the realm of security, the EU has yet to demonstrate it can play an active role in preventing conflict. Few truly buy the notion that integration has averted another war in Europe. Integration may have indirectly promoted peace by increasing prosperity, but the postwar peace in Europe has been overdetermined. Meanwhile, the Union has failed to demonstrate an ability to promote peace in other regions through its out-of-area missions. In diplomatic terms, the inability of European powers to speak with one voice makes it increasingly difficult to argue that the global influence of the Union amounts to more than the sum of its members. Add to this the failure to address the financial crisis, the poor handling of the Greek debt crisis, and the lack of a collective response to the recent migration crisis, and the merits of integration look rather uncertain.

As the world ponders the possibility of the unravelling of the EU, a stark irony presents itself. For more than half a century Europe has been a beacon of multilateralism—a unique experiment in regional cooperation and a model for the rest of the world. It now seems Europe could also become a beacon of disintegration—a leading example of states taking back sovereignty. If so, this will not be the fault of British voters alone, although Brexit may have dealt the coup-de-grâce to notions of multilateralism as a ‘European way-of-life’.

About the Author

Dr. Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni is Senior Lecturer in International Studies at Cambridge University. Her research interests include international organization, international non-proliferation regimes, transgovernmental networks, international environmental advocacy and European security and defense policy.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.

One reply on “The Global Crisis of Multilateralism”

It seems that there are good grounds and enough fields to promote multilateral aspects in the world.

At the present, the world needs multilateral cooperation to settle huge problems.

Obviously, no country would not able to cope with global challenges alone.

Even if multilateral cooperations have faced some challenges but political, social and technological trends all require strong responses through cooperation at global levels to cope with a lot of challenges.

In my opinion, EU multilateral cooperation will be stronger than now.

Moreover, the world will experience new aspects of multilateral cooperation.