This article was originally published by OpenSecurity on 26 May 2015 as part of the “States of Impunity” series.

Impunity is not simply a juridical, technical problem, or some sort of loophole in the law that lawyers, politicians, bureaucrats, and activists can close with greater effort. Impunity lies at the heart of a dispositive that encompasses, neutralizes and even recuperates almost all attempts to redress it. We have come to this disturbing realization on the basis of both empirical and theoretical attempts to understand how contemporary legal, political or civil-society practices run the risk, despite their benevolence, of falling into the propagandistic rhetoric, social conformism and bureaucratic indifference that feed impunity.

In his book The Social Production of Indifference Michael Herzfeld provides an especially interesting interpretation of the symbolic roots of modern western bureaucracy, which, he argues, is not result of a process of rationalization. Bureaucracy, whose role is so central to contemporary societies, seems to Herzfeld to be quite distant from–and almost stands in contradiction to–the foundations on which our contemporary world has been built. Contrary to commonly held opinion, bureaucracy does not create responsibility through clear hierarchies of command, but rather indifference and ‘deresponsabilization’. The circle of deresponsabilization is presented as a sort of fatalist theology, where bureaucracy becomes a system that constantly legitimizes its own behaviour precisely by shifting blame from one part of itself to another in a Kafkaesque manner that calls for bureaucracy’s reinforcement as an antidote to its own failings.

Our own experiences of global bureaucracies–including NGOs–however, have shown that we must distinguish between deresponsabilization and indifference. By projecting onto bosses, onto the locales in which they operate, onto experts who create distrust and suspicion, cosmopolitan bureaucrats resort to deresponsabilization but not to indifference. Or rather they start to move within a cycle of passion, fear, envy, and rage that become tools that feed the bureaucratic mechanisms themselves. They are sincere about their objectives and in their frustrations with their failures. Paradoxically, the continuous accumulation of information, to which their actions contribute, draws on the logic of modernity but produces a virtual rationality–the more they learn, the more they can blame others in an ultimately irrational cycle of scapegoating.

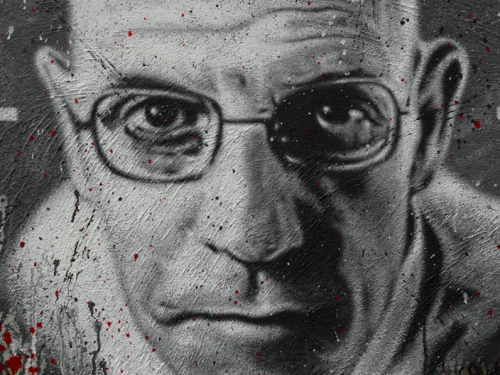

How, then, can we definitively cut the heads of the Hydra of impunity? Our response is to embrace the political posture suggested by Michel Foucault’s interpretation of parrhesia. Foucault’s quest for parrhesia proposes an original strategy to break the spiral of impunity. This strategy of speaking truth to power cuts through the conventional bureaucratic techniques for fighting impunity. In making this argument we seek not to discount on-going efforts but to provoke reflections on new practices and subjectivities, for only a radically new manner of living our lives can bring change.

Speaking the truth to power

At the beginning of his final lecture course, Le courage de la vérité, Foucault distinguishes between four modes of speaking truth (or modes of veridiction), namely those of the prophet, who is the enigmatic mouthpiece of the future truth of destiny; of the sage, who unwillingly shares his understanding of the foundational, unifying truth of Being; of the teacher, who is obliged to perpetuate the truth of his technical knowledge; and, finally, of the parrhesiaste, who dares to speak the truth about individuals and situations in their ethical singularity. Each mode of veridiction entails particular power relations between interlocutors, with that between the teacher and student, for example, being most complicit, symbiotic, and cowardly. Indeed Foucault, aspiring to parrhesia, mocks himself for his utter lack of courage. Contrary to the teacher, who seeks only to reproduce his knowledge and ultimately himself in continuity with a tradition, the parrhesiaste must be willing to risk losing their reputation, their friends and even their life when pronouncing their truth. They must ultimately lay their life entirely bare.

Through his genealogy of parrhesia in the ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Roman, and early Christian worlds, Foucault exposes the limits of political action and of philosophical critique as a means to subvert the discourse, practices, and techniques of (bio)power in general and to escape the veridictional cage of the market in particular. Only the ethical and aesthetic self-re-appropriation of the body remains as a possible avenue for a different life. Parrhesia was originally a political concept from the Periclean golden age of Athenian democracy, namely the right and duty of the citizen to speak freely before the assembly. With Socrates, it became an apolitical philosophical concern for the well-being of the self (epimeleia heautou) by way of the Socratic mission of overcoming the falsehood of opinion through remorseless frank questioning, even at the risk of violating the laws of the city and of condemnation to death.

Whereas Socrates embodied philosophical reason and ethical life practice, after him it is possible to distinguish between philosophical and ethical parreshia, as represented respectively in the Platonic and cynical traditions. Foucault pursues the distinction between these two forms of parrhesia. He first explores the dialogues on the death of Socrates. Then, he turns to the ascetic and ethical elements of parrhesia as pushed to their logical extreme in cynicism. Literally dog-like in his ethos, the cynic, whom Diogenes best personifies, strips his life of all convention, from clothing and manners to knowledge superfluous and survival, in an exemplary performance of parrhesia. The pure cynic represents radical alterity, a constant challenge to a life of conformity, but also a profoundly anti-political and potentially anti-philosophical stance.

This sequence from political parrhesia, to apolitical philosophical parrhesia (Socrates) and then to anti-political, ethical parrhesia (cynicism) is chronological. But more importantly, it is logically inherent to the mode of action within the different types of parrhesiastic relationship. The political parrhesiaste daringly speaks his truth to their interlocutor(s) in the name of their common good, and in so doing succumbs to the rhetorical device of flattery–the appeal to passions and interests–to arrive at the appearance of agreement. The philosophical parrhesiaste, adopts a critical, external stance towards politics and seeks a convergence of the logos of their and their interlocutors’ souls, in what Foucault calls a move from the rhetorical to the erotic. By contrast, the cynical parrhesiaste does not seek to attain a reasoned convergence of souls, and acts less to flatter, and more to performatively provoke his interlocutors. His mode of interaction is neither rhetorical nor erotic but aesthetic, in Foucault’s sense of a perpetual subversive practice in an art of living.

Subversion and the courage of truth

Although Foucault devotes most of his final two lecture courses to philosophical parrhesia and to its champion Socrates, by the end of Le courage de la vérité, it is clear that only the radical, provocative alterity of the ethical and aesthetic parrhesia of the cynical tradition responds to his personal aspiration for a different life–a life in truth–in a different world. Socrates’ philosophical parrhesia leads him to suicide in subordination to the laws of the city; the philosopher’s life of truth has no effect on power relations or, worse still, reproduces their effects. Although Foucault concludes the spoken portion of his final lecture course by affirming that the asceticism of cynicism opened the possibility of a ‘true life of truth’, he does not explain how the ‘aesthetic’ truth of the cynic can actually subvert the rhetorical ‘truth’ of politics any more than philosophical truth can.

While Foucault remains elusive about what a reactivation of the cynical ethos and ‘aesthetic’ would entail today, he does suggest some possibilities and limits for a subversive parrhesia in the face of the Hydra of impunity. In the second hour of his lecture of 29 February 1984, Foucault identifies three posterities of ancient cynicism in western culture: religious, political, and aesthetic. First, he considers the debt to cynicism of Christian asceticism, particularly in its monastic and heretical doctrinal as well as spontaneously anti-ecclesiastic forms. Second, Foucault points to revolutionary, activist, and leftist life-styles as modern, primarily 19th century attempts to scandalize and provoke with an exemplary life of truth, evoking today’s paradigmatic figure of the suicide bomber, ‘as practice of a life for truth right up to and including death (the bomb that kills even the one who places it)’. Foucault casts doubt on the subversive potential of a parrhesia that ultimately reverts to the emotive rhetoric and self-defeating conformity of political action.

Finally, he holds up the figure of the artist, who in the modern age becomes not just an exceptional person but especially a violent expositor of the cultural possibilities of life. Although Foucault celebrates the permanent violence of modern art as ‘wild eruption of the true’, he also recognizes its marginality to the massively effective political technologies of the present. Beyond the artists whom each of us can identify because they break with convention and shock us with their originality, singularity and authenticity, only to then become, with time, standard-bearers of general sensibility, we can also think of those ethical-aesthetic artists who embody something more than charisma only to become props of a system they despised–like the Che Guevara who spoke hard truths before the United Nations before being transformed into a popular consumer-cultural icon.

Where, finally, does Foucault leave us then? Inasmuch as Le courage de la vérité proposes a solution to the problem of impunity, the late Foucault offers us only the narrowest of escape routes from a bureaucratized world of scapegoating, namely parreshia, a life of truth in the cynical sense. The art of such a life does not consist in its pursuit of beauty but rather in the continuous mastery of an entirely personal practice of the self. Only through the extreme courage to pursue, continually and not exceptionally, our own and always singular ethos that gives content to an alternative form of life, outside the laws of scientific, philosophical and prophetic truths, can we–perhaps–slay the Hydra of impunity.

Laurence McFalls is Professor in the Department of Political Science, Université de Montréal. He recently co-authored with Mariella Pandolfi “Therapeusis and Parrhesia” in James Faubion, ed., Foucault Now, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2014 ; and “Global Bureaucracy: Irresponsible but not Indifferent” in Alessandro Dal Lago et Salvatore Pallida, eds., Conflict, Security and the Reshaping of Society: The Civilization of War, Routledge, Abingdon, 2014.

Mariella Pandolfi is Professor in the Department of Anthropology, Université de Montréal. She recently co-authored with Laurence McFalls “Therapeusis and Parrhesia” in James Faubion, ed., Foucault Now, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2014 ; and “Global Bureaucracy: Irresponsible but not Indifferent” in Alessandro Dal Lago et Salvatore Pallida, eds., Conflict, Security and the Reshaping of Society: The Civilization of War, Routledge, Abingdon, 2014.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.