In the first days of Occupy Wall Street’s Zuccotti Park phase, the protest was overwhelmingly homogenous. The movement was originally so dominated by white men that women in the group felt the need to form their own meetings—Fem GAs—in order to create a safe environment and open space for their concerns. Minority activists in New York City shared the concerns that the Occupy protests were ignoring crucial differences in the experiences of their audience, choosing instead to label all with an overwhelmingly white interpretation of “the 99 Percent.” African American and Latino activists were particularly worried about that organizing around the right to overtake a public space for long periods of time would detract from more sober public discussions of urban poverty and the effects of deepening austerity, while rhetoric surrounding police brutality towards protestors would distract from the daily trials minorities face in interactions with the police.

“We went out to Zuccotti Park. There wasn’t many people that looked like us. We thought we should be present,” said Malik Rahsaan, a New York City-based substance abuse counselor. Rahsaan left General Assemblies frustrated, feeling as if his voice as an African American man was invisible in the crowd. While Occupy could have offered minority groups a medium through which to express their opinions—African American and Latino communities have been among the most devastated by the economic downturn and long-term unemployment—on the failures of capitalism in their communities, some more radical black activists felt that white organizers would never have the same understanding of their economic situation.

“’Basically the economy in general got fucked up enough for other layers of society to feel it—what we’ve been feeling since we’ve been here,” rapper and activist Ness said to the Huffington Post. “‘That layer, the middle class and whites still have that sense of entitlement, that sentiment like, ‘This can’t be happening to me.’’”

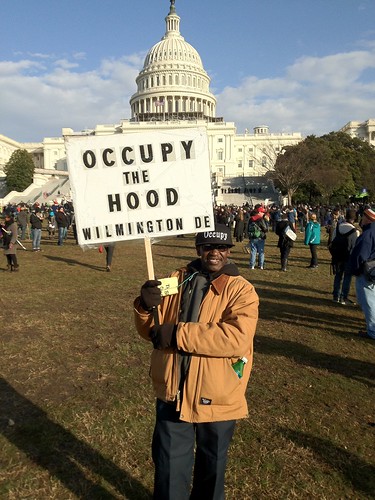

Perhaps most importantly, the focus on occupying a physical space as one of the end goals of the movement seemed to be unsustainable for building a national dialogue. So Rahsaan and others began organizing their own neighborhoods to not only advocate and protest for change, but also to use their own resources to revitalize their communities—hence Occupy the Hood. The system of community- and neighborhood-based organization spread throughout the broader Occupy movement after the Zuccotti Park evictions, breeding Occupy branches across the United States that were focused on specific community needs, including Occupy Our Homes and Occupy the Farm. Occupy the Hood’s model was successful in rallying a community around finding solutions to problems plaguing it within itself, that it became the model that Occupy turned to when it needed to reinvent itself.

Yet many members of Occupy the Hood report feeling alienated from or completely separate from the main movement. Amity Paye of the New York Amsterdam News wrote that participants at the July 2012 Atlanta Hood Week felt divided on the topic:

“’They kicked us out of [general assemblies],’ said Radee Westfield, one of the founding members of Occupy the Hood, explaining why he helped start OTH. ‘Everywhere we talked to Occupy the Hood members who had been Occupying since day one, they said the same thing…So we were like, you ain’t here to do nothing but secure your future, and if you’re not going to secure our future, then we’ll do our own thing.’”

Whether its members feel it is an Occupy branch or not, it has been successful in a number of different efforts to improve their communities.

In Detroit, where single mother and Occupy the Hood co-founder Ife Johari Uhuru works, activists have brought urban gardens back in style there and across the nation. Detroit turned to urban gardens out of necessity: as the city’s economic infrastructure collapsed, many regions of Detroit found their local grocery stores shuttered, and wide swaths of food deserts covered the city. Urban gardens became not only a way to provide a community with fresh produce, but it also became an effort in self-reliance so important to Occupy.

Another successful initiative is Occupy the Corners, an effort to reduce violent crime, neighborhood by neighborhood, by stationing observers on corners with statistically high crime rates. The effort to take back the streets has become so popular that Rev. Al Sharpton has publicly advocated for the strategy. However, such popular media attention misses the core value of such a campaign—in neighborhoods, such as New York City’s housing projects, where people are too afraid to come out of their homes, the solution has long been to increase police presence, which in turn often leads to increased suspicion between police forces and the communities they are purportedly protecting. Occupy the Corners functions as a sort of “Neighborhood Watch Program,” but rather than working in a white suburban neighborhood, it is taking on inner-city crime; in the process, it not only lessens the burden on police forces, but it also fosters a sense of ownership and civic engagement in a community that may have a long history of disenfranchisement.

Most importantly perhaps, unlike some of the white activists in Occupy who seek immediate change, Occupy the Hood seems to understand that a social movement can take years to make perceptible change, and patience is needed. As Preach, another co-founder, said, “We’re not here to reinvent the wheel. We’re just trying to get the wheel turning.”

Chrisella Sagers Herzog is the deputy editor for the Diplomatic Courier.

For further information on the topic, please view the following publications from our partners:

Rethinking US Security: Economics and Security

Welfare Regimes and Social Policy: A Review of the Role of Labour and Employment

The US Income Distribution and Mobility: Trends and International Comparisons

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Security Watch and Editorial Plan.