The 2008 Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) was meant to solve the seemingly intractable and bloody conflict raging, for decades, between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It was meant to give the disenfranchised and marginalized Muslim minority of the southern Philippines a homeland, self-rule and near-equal status with the Philippine central government after centuries of bloodshed. Instead of bringing the conflict, which reflects a centuries-old stuggle, to an almost clinically clean end, the collapse of the MOA-AD in the summer and fall of 2008 revealed the deep fissures at the heart of the conflict and laid bare the government’s inability and unwillingness to push through a potentially momentous peace deal.

The Memorandum of Agreement had, almost overnight revealed itself as little more than a fractured ‘Memorandum of Disagreement’ devoid of real political backing or popular support.

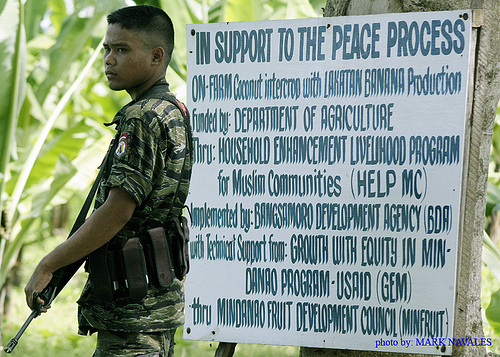

A fight with roots going back centuries to colonial and post-colonial struggles and largely caused by the gradual but steadfast marginalization of the Muslim peoples of the southern Philippines, the conflict has eluded resolution for decades. Poverty, lawlessness and sense of ‘not belonging’ in the broader state structures have kept up levels of anger and alienation in the Mindanao region, tapped into by groups such as the MILF and its banditry-loving offshoot, the Abu Sayyaf group.

Thousands have died and hundreds of thousands of Mindanaoans are refugees in their own homeland. They continue to suffer disproportionately from the breakdown of the peace process, the resumption of hostilities between insurgents and the armed forces of the central government, and from delays to desperately needed development projects. If ethnic, religious and historical fault lines were not enough to fuel the conflict, migration flows that have brought Christians from neighboring regions to Mindanao further complicate the demographic make up of arguably one of the most complex conflicts in the region.

Any hope, then, for peace?

Several recent reports have noted that progress is unlikely until the current president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, steps down in May 2010. Although her government presided over much of the negotiating that led to the 2008 MOA-AD, she failed to rally support and ensure political backing for the deal. The national and political logic for a compromise with a disconnected and impoverished minority was simply never established. On a popular support level any politician that now wishes to see an end to the conflict will have to work in an increasingly complex environment – one that is perhaps more fractured than it has ever been – and with dwindling support from the majority populace.

Political logic, will and flexibility would be required of all parties to jump-start the moribund process. A ceasefire between MILF insurgents and government forces would be a start. External support would be equally key. Malaysia provided such stewardship in the last round, but is unlikely to return since a dispute with the Philippines over sea boundaries is brewing. Qatar has come up as an option. Even former members of the Northern Ireland peace process have visited Manila and offered their advice.

But how about Martti Ahtisaari and his Crisis Management Initiative? With success in Aceh, international clout and a Nobel Peace Prize under his belt, Ahtisaari might have the right credentials to push the two sides to a solution.

Now, Mr. Ahtisaari, could you hop on a plane tomorrow?