This article was originally published by War on the Rocks on 9 March 2016.

On September 11, 2013, Russian President Vladimir V. Putin, writing in The New York Times, issued “A Plea for Caution From Russia.” Putin sought to communicate directly with the American people, warning against U.S. and Western unilateral military action in Syria — in response to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons against its own citizens — without the authorization of the United Nations Security Council. Such an action, Putin warned, would be destabilizing, deepen the cycle of regional violence, and potentially throw “the entire system of international law and order out of balance.” Putin further chastised the United States for its alarming tendency to intervene militarily in overseas civil wars and implied that U.S. strategies for dealing with problem states were encouraging the spread of nuclear weapons. Putin’s plea: “We must stop using the language of force and return to the path of civilized diplomatic and political settlement.”

We know that this “plea for caution” was nothing more than an effort to protect a Russian client state dressed up in the language of political and legal principle. How else can we understand Russia’s unilateral, unsanctioned military intervention in the Syria conflict in September 2015? Cynical? Maybe, but of even greater concern than Russian hypocrisy in the Middle East is its nuclear saber-rattling in Europe and elsewhere. On this issue, it is imperative that the Kremlin heed a genuine plea for caution from the United States and reconsider its policy of using the language — and practice — of nuclear force to coerce and intimidate. This policy truly does have the potential, to use Putin’s words, to be destabilizing and to undermine the international order. And it could set in motion responses that would heighten strategic competition and risk and, in the process, damage Russia’s own interests.

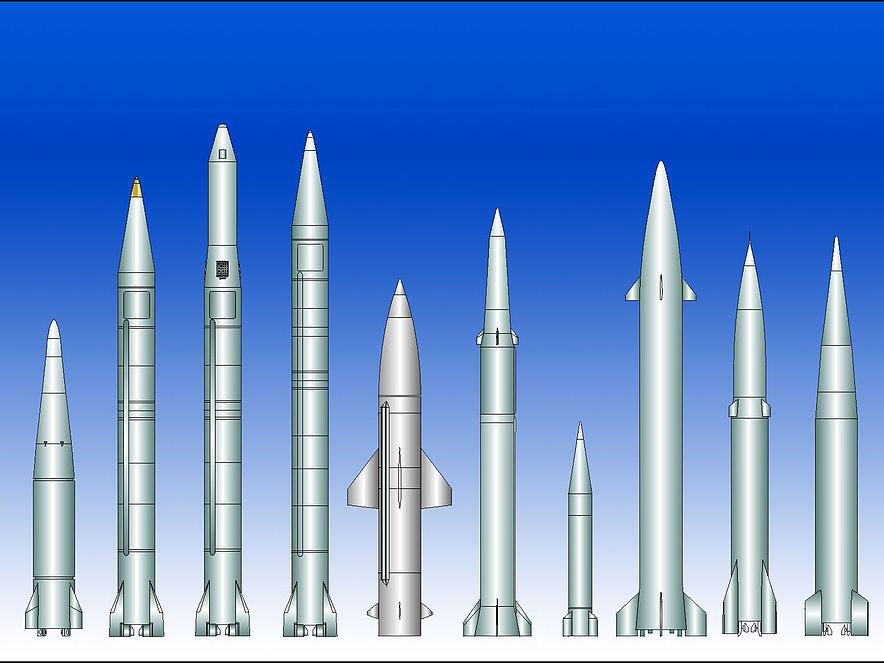

Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling is well documented — open threats to use nuclear weapons, statements by government officials and government-affiliated media personalities highlighting Russia’s nuclear doctrine and capabilities, encroachments by Russian nuclear-capable aircraft near the airspace of the United States and its allies, and exercises that simulate tactical nuclear employment to terminate a local conflict. Russia’s military doctrine has long provided for the possibility of initiating the limited use of nuclear weapons in order to “de-escalate” a regional war. The intent is to convince the West to accept a Russian fait accompli against a NATO member rather than assume the risks of making a counter-attack.

Is Putin actually prepared to be the first head of state to order the use nuclear weapons since Harry Truman did so in 1945? We don’t really know. Publicly announced military doctrine may not be a reliable predictor of decisions the Russian president will make during the fog and stress of war. But it does suggest that Russia has a very different conception of nuclear weapons than the United States and its allies. For Moscow, nuclear weapons have broad political and military utility, are a potent means to coerce others and shape the course of crisis and conflict, and play an important role in Russia’s approach to contemporary warfare. The fact that Russia continues to invest in the short-range nuclear forces best suited to execute its doctrine of de-escalation and has chosen to violate the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty to enhance its theater-range capabilities underscores its broad reliance on nuclear weapons.

Clearly, Russia sees advantage in ratcheting up a sense of nuclear peril in Europe to advance its regional strategy. Open or thinly veiled nuclear threats, whether by word or action, are a Russian tactic to intimidate individual governments and NATO as a whole. By raising the specter of nuclear war, Moscow seeks to induce fear, caution and, ultimately paralysis in contemplating opposition to Russian political and military moves. Looking at an alliance of 28 nations unlikely to view an emerging crisis in precisely the same way, it is not surprising that Moscow sees this tactic as something that might successfully create divisions within NATO and thereby weaken, delay or prevent effective NATO responses.

Observing Russia’s seeming infatuation with nuclear weapons, and its apparent belief that these weapons can be leveraged or used for coercive purposes, it is reasonable to ask whether Putin and his advisers appreciate the danger of persistent nuclear saber-rattling and the incalculable costs for all — not least Russia — should a regional war go nuclear. In the last year, some Western leaders have openly posed this question. In May 2015 NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg observed that Russia’s use of nuclear rhetoric and exercises was “unjustified, destabilizing, and dangerous” and that the Kremlin was failing to heed lessons of the Cold War that “when it comes to nuclear weapons, caution, predictability, and transparency are vital.” U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter echoed this theme in November, when he stated, “Most disturbing, Moscow’s nuclear saber-rattling raises questions about Russian leaders’ commitments to strategic stability, their respect for norms against the use of nuclear weapons, and whether they respect the profound caution nuclear-age leaders showed with regard to brandishing nuclear weapons.” It’s not clear Moscow is hearing these messages.

It’s time to tell Moscow more clearly that its policies and attitude ultimately will be self-defeating, for a number of reasons. First, while the United States and its allies will not mimic Russia’s reliance on nuclear weapons or its practice of making nuclear threats, they are taking steps to strengthen NATO’s deterrence and defense posture in ways that should reinforce both resolve and capability to resist Russian coercion. The message to Russia must be that it will not gain any strategic benefit from making nuclear threats or initiating the use of nuclear weapons. Second, Russia’s approach is likely to deepen the U.S. commitment to non-nuclear capabilities, from expanded missile defenses to advanced long-range conventional strike systems, that could complicate Russia’s strategy and produce an outcome Russia openly fears — a renewed U.S. reliance on a policy of damage limitation and Russian vulnerability. For example, while NATO has deployed ballistic missile defenses to respond to threats from the Middle East, it is not difficult to imagine continued Russian belligerence leading the alliance to consider how these capabilities could be used in a local conflict to counter Russian short- and medium-range missile threats and thereby weaken or eliminate some of the coercive nuclear options available to Moscow.

Third, while today the West does not openly challenge the legitimacy of the Putin regime, at some point it will become easier and more acceptable for the United States and at least some of its allies to conclude that only a change in leadership in Moscow can offer safety from a government that routinely brandishes nuclear weapons and seems prepared to use them to prevail in a local conflict. If the Kremlin truly fears a “color revolution,” it should consider the role its nuclear policies might play in shaping attitudes about the regime’s legitimacy. Nuclear swagger will not buy Moscow the respect it craves, and is more likely to alienate other states and feed perceptions that Russia is a danger to global security. Additionally, Russia is modeling bad behavior that may further encourage states like North Korea and Pakistan to adopt strategies based on open nuclear threats. This may not directly affect Russian interests in the near term, but it will help to inflame regional tensions and undermine global efforts to reduce nuclear risks.

Finally, and most importantly, Russia’s posture makes it more likely that a nuclear crisis will get out of hand and result in unintended escalation. Fortunately, nuclear crises have been rare, but is anyone comfortable predicting that cooler heads are certain to prevail in the next Cuban Missile Crisis? If Putin or those advising him believe that detonating a small number of low-yield nuclear weapons would not breach a fundamental threshold of conflict, they need to be reminded otherwise. If Russia’s leaders believe they can fine-tune a process of escalation and safely predict the outcome of a nuclear crisis or even a limited nuclear exchange with the United States, they must be made to see that this is an illusion. If these gentlemen do not share the sense of fatal vision associated with nuclear war that an earlier generation of Kremlin leaders seemed to possess, we need to find a way to restore it.

Persuading Russia to show nuclear restraint should be a priority. President Obama should address this challenge directly. Doing so would be consistent with his longstanding commitment to reduce nuclear risks and signal that this is a serious issue. Beyond this, publicly and privately, through official and unofficial channels, and at the political and military levels, the message should be that such restraint is in Russia’s own interest and essential to avoid a nuclear crisis whose outcome could be devastating to all of Europe. The urgency of conveying this message is one reason the United States, NATO and Russia should be talking to one another about European security. Freezing political and military contacts is understandable following Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. But not talking also contributes to risk. The resumption of some military-to-military contacts would provide a useful opportunity to convey the West’s deep concerns about Russia’s nuclear posturing.

To reinforce a tough message about restraint, the West should be prepared to offer a message of reassurance. The United States and NATO have not questioned the legitimacy of the Putin government and do not seek to foment any kind of revolution in Russia. NATO’s military preparations are not intended to encircle or coerce Russia, but to deter and defend. If NATO must act to defend one or more its members, its objectives will be limited and will not include the overthrow of the Putin regime or the destruction of the Russian state. To the degree Russia — however mistakenly — sees the West’s objectives in such a conflict as essentially unlimited, its instinct to rely heavily on nuclear threats will only be reinforced. In turn, Moscow must understand that reassurances about challenges to regime legitimacy and limited objectives in response to Russian aggression may not survive its first use of nuclear weapons.

Ultimately, our goal should be to minimize the role of nuclear weapons in East–West relations, keeping them in the background even when, as is inevitable, tensions rise and crises brew. As uncomfortable as it makes many people, global security still depends on nuclear weapons and the stabilizing effects of sound deterrence policies. But while responsible nuclear policies help keep the peace, irresponsible ones create instability and heighten risk. Russia certainly has the right to defend itself, and to rely on nuclear weapons to do so. It also has an obligation to exercise care and caution in how it wields the most destructive weapons ever created.

Paul I. Bernstein is Senior Research Fellow at the Center for The Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction, Institute for National Strategic Studies, at National Defense University in Washington, DC.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.