This article was originally published by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) on 5 July 2019.

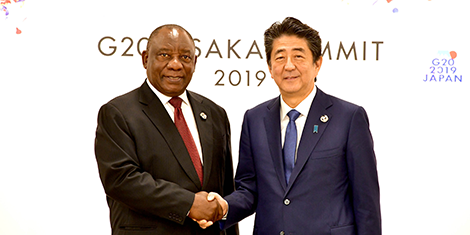

Africa’s ‘development partners’ still struggle to define and manage their relationship with the continent. This was apparent at the G20 summit in Osaka that ended on Saturday.

The G20 has been accused of treating Africa exclusively as a development problem, thereby excluding it as an equal participant from deliberations about climate change, the future of work, the global trading system and other mammoth issues the G20 presumes to be capable of addressing.

‘If one lacks a seat at the table, then one is probably on the menu,’ says Cobus van Staden of the SA Institute of International Affairs. Perhaps, although Africa is represented through South Africa’s permanent membership and the regular participation of the African Union and New Partnership for Africa’s Development chairs at summits. The developed world clearly dominates, but Africa isn’t the only other region that’s under-represented.

South Africa does try to drive Africa’s case at the G20, though with limited success. It may have helped push for tougher action on egregious tax dodging by multinational companies which has cost the continent dearly. It has failed – along with others – in trying to secure a free and fair global trading system.

The G20 has tried to ‘normalise’ its relationship with Africa, though not, as Van Staden suggests it should, by inviting more African countries into the charmed circle. Rather it has attempted to evolve the relationship away from the traditional donor-recipient nexus.

At the 2017 G20 summit, the German hosts introduced the Compact with Africa as the latest iteration of the international community’s long and often anguished development relationship with Africa. Instead of dishing out dollars for socially uplifting projects in the traditional way, the compact proposed that individual countries enter into compacts with individual G20 states to help improve their environments for mainly private sector investment.

The reward for African countries would be measured not in dollar terms but in increased investment including for infrastructure, to stimulate development through normal economic activity, boosting growth and creating employment. So in their compacts the African countries have focused on reforms such as making it easier to start a business, improving contract dispute resolution, reducing import and export time, and strengthening insolvency law.

Two years later, the picture is a little mixed. For one thing, only 12 of Africa’s 54 countries have entered into compacts with G20 countries – Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, Tunisia and Togo.

That list is interesting. West Africa is well represented, so is North Africa and to a lesser extent, East Africa. Central and Southern Africa aren’t represented at all. South Africa, which is a G20 member and co-chairs both its development working group and the Africa Advisory Group that manages the Compact with Africa, is absent – perhaps because it feels it is adequately managing its investment environment alone.

That aside, the progress of these 12 countries participating in compacts has been encouraging, though some warning lights are flashing. In its latest assessment of the Compact with Africa published for the summit, the G20 said the compact countries were ‘significantly outperforming global and regional growth projections.’

All 12 compact countries had improved their ease of doing business scores, with nearly all featuring in the group of top 10 reformers globally. All but two had improved their rank among the 190 countries measured by doing business.

‘Rwanda, which ranked 56th in 2017, now ranks 29th in the world, ahead of such countries as France, Poland and Belgium. Côte d’Ivoire has improved its ranking by 20 places; Togo has moved up 17 places; and Guinea has moved up 11 places and 1.81 percentage points.’

These worthy efforts haven’t always translated into greater investment though, where ‘the picture is more mixed’, the report says. Seven of the compact countries – Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guinea, Morocco, Rwanda and Togo – attracted more foreign investment in 2018 than 2017. ‘Across all the Compact countries, however, the trend is downward, with $30.7 billion in 2018 down from $54.4 billion in 2017.’

The report attributes this mainly to the fact that in 2017, Egypt and Ghana had US$38 billion in energy sector investments which distorted the comparison, leading to a predictable drop-off in those two countries in 2018, with Egypt attracting US$12.4 billion and Ghana US$840 million in announced investments.

The report cautions that the failure of reforms to immediately translate into sustained and increasing foreign direct investment ‘is a reminder that factors, other than macroeconomic stability and a commitment to business-friendly reforms, drive levels of investment.’ Just one of these is the need to boost human capital, mainly through education.

The African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET) warns that the relatively slow flow of investment may be starting to breed fatigue with the G20’s approach to compacts. The main cause for concern, it suggests, is that compact countries often don’t really understand the ‘indirect’ development model.

Although there are other development compacts – such as the United States’ Millennium Challenge Corporation – these follow the traditional development model where developing countries commit to policy changes in exchange for pre-defined rewards. The Compact with Africa does not guarantee ‘the reciprocal “promise” of investment,’ ACET notes. ‘The G20 governments have largely not promised direct support.’

‘This results in a value proposition that is not clear … there are high expectations of significant foreign direct investment from G20 countries resulting from [the compact].’ ACET blames the G20 governments in part for failing to sufficiently encourage their companies to invest in compact countries.

But the main problem seems to be one of managing perceptions and expectations. African compact countries need to be made aware that reforms put in place under the Compact with Africa are good things in themselves, whether or not they immediately open the taps of investment. This is inevitably going to be a long haul.

About the Author

Peter Fabricius is an ISS Consultant.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.