This article was originally published by Defence-In-Depth on June 10, 2015.

The politics of war and peace in space is an overlooked field. Space is a quiet and lonely place in war studies – despite space systems performing critical infrastructure roles in war, peace, politics, economics, and nuclear stability. In the mid-1990s John Sheldon and Colin Gray bemoaned the fact that there is no ‘Mahan for space.’ Neither writer apparently considered the possibility that they had answered their own plea, or in other words, that there is a Mahan for space: it’s Alfred Thayer Mahan. The 19th century navalist is one of a constellation of strategic theorists (such as Clausewitz, Castex, Corbett, to name the most prominent) whose work I am applying to create a spacepower theory intended to inform the diverse strategic problems conflict in this new medium might pose.

What are the grounds for analogy from terrestrial warfare to space warfare? How can universal principles about war at the highest levels where politics and violence meet – i.e. strategic theory – be reasonably crafted and constructively used? I believe there are two crucial grounds for analogy from the Earth to space. The first is Clausewitz’s most famous dictum that war is a continuation of politics with the addition of other means. This idea, that war is political, allows Clausewitz to connect any wars that are infinitely variable in their details and see what is common between them in order to learn more about why certain decisions were made and the conditions within which those decisions were made. This is done by asking questions that are based on a grasping of a few universal principles. Regardless of the situation, a universal principle should help develop useful questions to ask of any given situation. The political nature of war pervades whatever we may understand as war. This provides a basic ground for examining wars and helps train the individual to appreciate why wars are so different. Why is one war more costly than another? Why was one war forfeited when the costs were so little when ‘total’ wars have destroyed entire states before resistance was crushed? The political aspect helps Clausewitz develop a strategic analogy for the better understanding and study of the phenomenon of war. This in turn should help practitioners better grasp their craft. Identifying thematic commonalities among wars helps identify their particular differences. Readers familiar with Clausewitz’s ‘remarkable trinity’ will no doubt appreciate the universality of passion, reason, and chance in every war, yet their manifestations are innumerable in their forms in history.

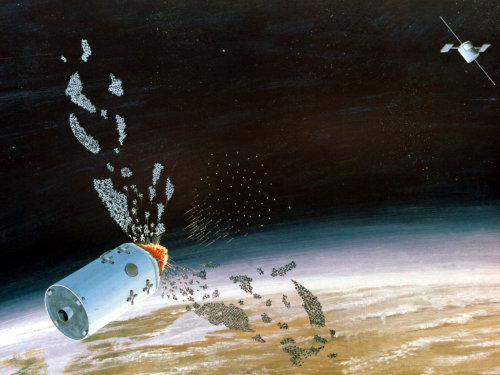

But what does this abstract theorising mean for space warfare? Space warfare – actions taken to destroy or interfere with enemy space systems – is not inherently escalatory, limited, ethical, a prelude to nuclear war, or inevitable. Space warfare will be a reflection of the political conditions of any belligerents that fight who happen to have a capability in using or denying space systems. Clausewitz, through stressing politics, brings the human element and the wider prevailing strategic context of any political violence to our attention. A recent series of articles on anti-satellite weapons and the risks of nuclear war fail to mention the realities of second-strike nuclear capabilities, the politics and psychology of nuclear threat perception, and the imponderable systemic political context that any single decision to attack will be within. Instead, select technological devices are ascribed a political value (stabilising or destabilising) without connecting the discussion to any political context between the established nuclear powers. These narrow arguments fail to adequately put space warfare in its strategic and political contexts and can impose blinkers on strategic thinking. Spacepower theory should help put these narrow arguments in their strategic contexts, and illuminate factors that have been omitted – in this case mutually assured destruction, second strike capabilities, and the politics and psychology of deterrence.

The second ground for analogy is that space warfare is best thought of as being comprised of as celestial lines of communication (a well-developed idea by John Klein) and over the contest of a command of space. This of course is analogical to concepts of sea lines of communication and the command of the sea popularised by the seapower theorists Alfred Thayer Mahan and Julian Corbett. Along these lines or communication, information, wealth, and satellites travel either on Newtonian orbital paths or through data streams in the electromagnetic spectrum. Like sea lines of communication, denying the use of these celestial lines of communication may have an impact on a war. Indeed, the more an economy and military depends on those celestial lines of communication, the more lucrative a target those lines may become for an adversary. Though there are many problems by other authors on their use of seapower theory for spacepower theory, Mahan and Corbett, in conjunction with other lesser-known seapower thinkers make outer space more of a coastline than an open sea. Indeed, that is a central aspect of my spacepower theory. But, as Clausewitz and Mahan often argued, strategic creativity and good leadership escape quantitative analysis and defy mechanistic approaches to understanding war.

These two basic grounds of strategic analogy from warfare on Earth to outer space serve to illustrate how ‘Clausewitz in orbit’ works. But with such a qualitative approach, it is hard to declare success. Rather, only discussion and the academic process will deem spacepower theory of any use. Indeed, it is impossible for spacepower theory to be ‘correct’ – it can only be useful for the strategic education of the individual. This approach may be distasteful to some in an era of increasing quantitative analyses of educative practices and performance analysis.

By saying that war is political, I believe we can better see how thinking of space warfare must be mindful of Earthly politics and the human element. In this context, Clausewitz’s other concepts – of passion, reason, and chance, of friction, of the strategic defence being the stronger form of war – make more sense and become easier to apply critically to scenarios where our focus may be on what happens in Earth orbit and its interactions with terra firma. In a similar vein, when we use an analogy of celestial lines of communication and the command of space, it helps us to better think critically about other problems such as how decisive space power can ever be in war, what is the influence of spacepower upon (future) history, and how can belligerents respond to and learn from various forms of spacepower?

The critical application strategic analogies have led me to seven propositions of spacepower theory:

- Space warfare is about the command of space

- Space is a distinct geography but it is not isolated

- Preponderance in space does not guarantee preponderance on Earth

- The command of space is about exploiting celestial lines of communication

- Earth orbit is a cosmic coastline

- Spacepower finds itself in a geocentric mindset… and may outgrow it

- Dispersion is a condition and effect of spacepower

These propositions show the headline outcomes of Clausewitz, et al., in orbit. As I near the end of my PhD research, I hope that my framework for spacepower theory helps take the next step in strategic thought about space, and to help understand more about astropolitics and questions of war and peace in orbit. Understanding the epistemology of strategic theory in a way that Clausewitz and Mahan did helps put limitations to my theory, but stresses their strengths and usefulness (see Jon Sumida’s Decoding Clausewitz and Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command for discussions of this pedagogical approach to strategic theory).

It is necessary to finishing by stressing what strategic theory is not. Most strategic theory is not there to provide answers or axioms for success. In addition, knowing spacepower theory is not a prerequisite for good command judgment in space warfare. Neither is grasping spacepower theory a guarantee of making the best decisions. Strategic theory is meant to help an individual in one’s self-education on military-political matters by making problems more accessible to a reader in the absence ‘genius.’ Spacepower theory should not only aim to make complex political matters over war and peace in space more comprehensible by grasping at the political roots of space warfare, but also to pave the way for an appreciation of creative and well-founded strategic thinking and command judgment in a realm so often dominated by technical or scientific mentalities.

This is what a Mahan for space is: distilling his Clausewitzian attitude to teaching command and strategy, and applying the seapower concepts of lines of communication to Earth orbit. With spacepower theory, outer space need not be such an undiscovered country.

Bleddyn Bowen is a doctoral student at Aberstwyth University specializing in Spacepower Theory, Clausewitzian Theory and Astrostrategy.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.