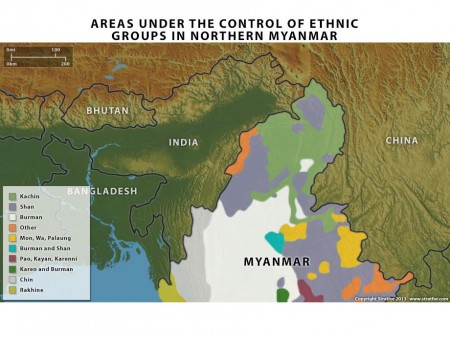

Northern Myanmar is strategically important to Beijing as a supply corridor and as a buffer between China’s ethnically diverse southwestern provinces and southern Myanmar. The heightened tension in northern Myanmar in the past several years presented Beijing with challenges regarding border security and maintaining a balance between Naypyidaw and various ethnic forces with strong connections to Beijing.

While Beijing remains the most important mediator in the ethnic conflicts, its broader strategic interests in the country played a part in Beijing’s reluctance to openly engage with ethnic forces involved in the fighting. With Naypyidaw gradually gaining support from the West, Beijing has to contend with Western threats to its energy and transport interests and with ethnic issues threatening stability along its border.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman on Jan. 17 confirmed that an artillery shell from Myanmar forces landed in Chinese territory Jan. 15. This was the fourth shell to land inside China since conflict between the Myanmar government and the ethnic militias heightened in late December 2012. The spokesman called on involved parties to start negotiations for a cease-fire.

The comments came days after Myanmar armed forces intensified attacks against the ethnic Kachin Independent Army. Fighting was concentrated around the Kachin forces’ headquarters in Laiza, a transportation hub and port along the Sino-Myanmar border, in line with the Myanmar army’s strategy of cutting off access to Laiza and expanding its control of supply lines in an effort to isolate the Kachin Independent Army. On Jan. 14, Myanmar’s army fired artillery shells into the center of Laiza, killing three civilians, according to Kachin fighters. This was the first time Myanmar forces directly bombarded Laiza.

Since the military offensive against the Kachin fighters began in June 2011, the Kachin’s occupation of mountainous jungle and use of guerrilla strategies have kept the Myanmar army from effectively crushing the Kachin Independent Army. However, Myanmar’s armed forces, with their air force advantage, have been able to seize a number of hilltop outposts, including the strategic Point 771 located approximately 7 kilometers (about 4 miles) outside of Laiza.

China’s Concerns

The spillover of fighting in Kachin region affects stability along China’s southwestern border, an area with a large ethnic population. Tens of thousands of Myanmar refugees have already poured into Yunnan province. The spillover also affects China’s investments in Kachin and, more important, increasingly challenges Beijing’s ability to influence ethnic groups in the region, many of which have cultural and ethnic connections to China and remain under Chinese economic and political influence.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Beijing supported Burmese Communist forces in the country’s north by directly arming and financially supporting ethnic rebels and dispatching its own forces, in part to counter the hostile Burmese government and facilitate the spread of communism. Since China’s relationship with the country’s military government normalized in the 1990s, Beijing withdrew its direct support of ethnic rebels in northern Myanmar and assumed the role of mediator to maintain a balance between Myanmar’s central government and the ethnic forces.

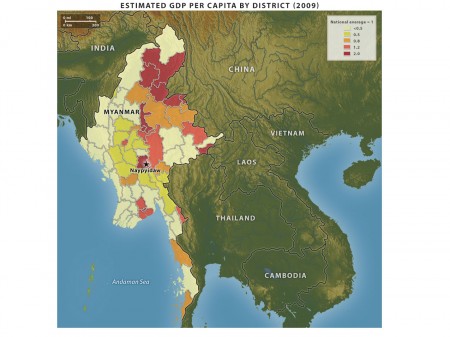

At the same time, international sanctions gradually isolated Myanmar’s military regime. This allowed Beijing to gradually build its political influence and economic presence in the country to pursue more strategic needs, including the construction of oil and natural gas pipelines using Myanmar’s sea access and a strong investment presence that largely dominated Myanmar’s economy.

Maintaining Influence

With Myanmar’s growing importance to Beijing over the years, the changing dynamic between China and Myanmar again forced Beijing to recalculate its relationships with the ethnic forces and Myanmar’s central government in order to keep its energy corridor open. While Beijing remains the most important mediator in the ethnic conflicts, it had largely avoided openly engaging with the ethnic forces, many of which perceived Beijing as a reluctant negotiator. Moreover, some ethnic groups saw Beijing’s call to agree to an initiative assimilating ethnic forces into the Myanmar military as a betrayal. Beijing’s conciliatory move created distrust around China’s role as mediator.

Perhaps only after an incident in Kokang in 2009, when the Myanmar army crushed an ethnic force with connections to China occupying the Han Chinese-populated Northern Shan’s Special Region-1 in Myanmar, did Beijing realize that Napyidaw’s appetite for ethnic unity poses a serious challenge to China’s security and influence along the border. Moreover, by then Myanmar’s gradual opening to the world had created new difficulties, giving Beijing growing competition in securing its interests in the country.

Myanmar’s government believes that a prosperous country relies primarily on national unity as it opens to the rest of the world. The government is determined to consolidate northern Myanmar either through cease-fire negotiations or military offensives. Beijing can ill afford to lose its influence in the ethnic regions of northern Myanmar; doing so would result in the loss of a buffer region and diminish its bargaining power with the Myanmar government, allowing Naypyidaw to further distance itself from Beijing. While China has maintained its leverage in the ethnic conflicts, it has refrained from strongly pressuring the Myanmar government. But with Naypyidaw gaining gradual support from the West, Beijing could find itself struggling to maintain its influence to ensure access to its trade and energy corridors in Myanmar and competing against Western threats to its energy and transport interests in the country.

This article was originally published by ISN partner, STRATFOR.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Whatever Happened to Myanmar as the “Outpost of Tyranny”?

Myanmar’s Ethnic Divide

Myanmar: Storm Clouds on the Horizon

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s featured editorial content and Security Watch.