This article was originally published by Harvard International Review on 7 February 2017.

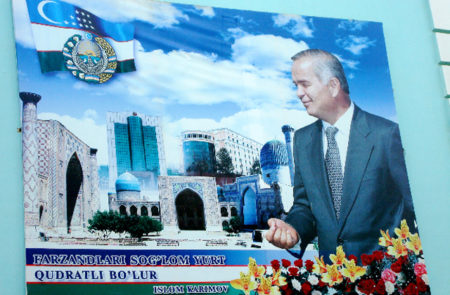

On August 29, 2016, the president of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Four days later, the country lost its first and only president. Karimov had been exerting his influence in Uzbek politics since 1989 as the last secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, which later became the People’s Democratic Party of Uzbekistan (PDP). It may not come as a surprise that his rule was often mired by reports of human rights violations and declarations of autocratic powers to squash any political opposition.

Though the transition of power to the new provisional government may be relatively smooth, Uzbekistan remains fraught with challenges. For now, the Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoev has assumed temporary control until elections are held later this year. The new leadership of Uzbekistan must address the late Karimov’s legacy grappling with a fragile economy, the separatist movement in Karakalpastan, increasing interest of foreign powers in exerting influence over Central Asia, increasingly complex water allocation amongst Central Asian states, and backlash from the previous government’s repressive stance towards Islam.