This article was originally published by War on the Rocks on 7 January 2019.

In January 2018, the elegant Bozar theatre in Brussels was the backdrop to a People’s Republic of China video montage of key historic events on the occasion of the Chinese New Year Gala. While a Chinese singer on stage belted out a patriotic song, a large screen behind her displayed an enormous Chinese flag flying in the wind followed by film footage of key milestones including China’s first nuclear detonation, admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the launching of its first aircraft carrier. Members of the audience, which included diplomats, European officials, and military representatives, collectively caught their breath while watching. It’s not that they were impressed, although they might have been. They were aghast. China’s military might, growing economic power and technological advances, have served as a wake-up call to many policymakers in Europe. Brussels’ rather outdated “missionary” narrative of helping to shape and influence China according to their policy preferences was clearly not how the future was going to unfold.

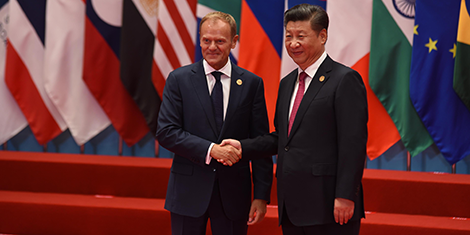

China’s economic and military rise was accompanied by a broader shift in the Washington-Beijing-Brussels strategic triangle. Under the Trump administration the United States was focusing more and more on China as a “strategic competitor.” Most European leaders perceive President Donald Trump as unpredictable and unreliable, which has led to efforts to promote European strategic autonomy. Recently, Donald Trump reversed 17 years of U.S. military doctrine with the announcement of the departure of U.S. troops from Syria and Afghanistan. This prompted what many Europeans considered the last “adult in the room,” Defense Secretary James Mattis, to submit his resignation letter. The cascading effects of these decisions will have implications for European security.

In December 2018, Beijing issued a new white paper on relations with the European Union, marking anniversaries in E.U.-China relations. The paper follows familiar themes and lists areas of cooperation in many sectors including high technology. It details what Beijing expects of Brussels on Taiwan, Tibet, and other issues. In keeping with the times, it includes cooperation in the fight against “fake news”, potentially threatening freedom of speech. It also suggests that the European Union should stand with China to oppose (American) unilateralism. China signaled that it is ready to fill the gap left by a withdrawing United States.

For a couple of decades, the European Union pursued what Jeremy Rifkind called the “European dream” of post-modern bliss. Some European officials declared that the European Union “does not do geopolitics,” and indeed some E.U. member states might have thought they did not have to worry about the geopolitical consequences of their actions. The European Union thus allowed itself to become the playground of big powers. Europe’s carefully cultivated complacency allowed China maximum room for maneuver. Russia conducted influence operations and displayed assertiveness in Ukraine and the European neighborhood.

However, Europe’s non-geopolitical view appears to be changing as many European countries individually and the European Union collectively start to see China as a potential competitor. In addition, China’s Made in 2025 strategy served as an important wake up call to high-tech European industry.

As both Europe and India awake to the China challenge will the European Dream mesh with India’s “Yuva Shakti” — “Youth Power”? In December 2018, the European Council adopted the conclusions of the E.U. Strategy on India. Will this mark a new phase in E.U.-India relations? Previously, Brussels was accused of benign neglect towards India with the European Union’s Sinocentric focus. This new document signals the E.U.’s desire for a “deeper and broader engagement with India” with the aim to build a partnership for sustainable modernization and to support the rules-based global order as well as “pursuing security interests”. It remains to be seen what concrete actions will result from this paper.

In February 2017, Italy, France, and Germany asked the European Commission to draw up a proposal to screen foreign investments in Europe (FDI). Although no country was named, it was clearly understood that the proposal was aimed at Chinese FDI. I was told privately, due to the sensitivity of the subject, that the proposal barely made it through the trilogue process, that is negotiations between the European Council, Commission and Parliament, because of resistance from certain Member States that court Chinese investment, notably Italy. The current text is a watered-down compromise that critics complain has no teeth.

The FDI screening request came at a time when many Europeans were increasingly critical of the fact that their countries were open to Chinese investment, but not allowed the same standard of reciprocity, market access, and level playing field in China. Unlike E.U. companies, Chinese companies typically represent Chinese state interests. And, Chinese FDI in Europe increased from $700 million in 2008 to $30 billion in 2017.

China’s investments in the Port of Piraeus in Greece, with the plan to build a transport corridor from there through Belgrade and Budapest to the rest of Europe, have bought China influence in Greece and Hungary. However, the bulk of China’s FDI has been in the larger economies of Germany, France, and the UK with an emphasis on technology that Chinese investors cannot purchase in the United States.

The tipping point on reciprocal investment came with the sale of Kuka, a leading German robotics maker, to Chinese-owned Midea. Analysts discovered that German engineers now design robotics for the People’s Liberation Army, which does not make for an attractive transatlantic narrative. Since then Germany has tightened its own national regulations on FDI.

China is pursuing a “China dream” of national rejuvenation and of higher standing on the international stage. It also clearly intended to play a greater military role in Europe’s neighborhood, which included conducting a joint military exercise with Russia in the Black Sea and in the Mediterranean and another one in the Baltic Sea accompanied with missile tests off the coast of Kaliningrad, which rattled European Member States in the region.

No longer can European policymakers simply dismiss China as a far-away power — it is already carrying out influence activities inside the European Union alongside Russia. In a February 2018 report, two German think tanks highlighted Beijing’s increased “political influencing efforts in Europe.”

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel warned against China’s growing influence in the Balkans. And German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel at the Munich Security conference in 2018 expressed serious concerns about Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative: “China is developing a comprehensive system that is not like ours, not based on freedom, democracy and human rights.”

Nevertheless, China’s economic statecraft has created divisions within Europe as well as sub-regional groupings like the 16+1 that make it difficult for Europe to speak with one voice. For example, in March 2017 Hungary refused to sign an E.U. joint letter on the alleged torture of detained lawyers. In June 2017, Greece blocked an E.U. statement at the United Nations criticizing China’s human rights record. In July 2016, Hungary, Greece, and Croatia vetoed a critical reference to Beijing in an E.U. statement on territorial claims in the South China Sea. These examples demonstrate Beijing’s successful wedge strategy in Europe and ability to influence E.U. policy.

There are still areas where Europe is more advanced so Europe should think hard on how to cooperate with China while keeping a technological edge. This is very important for Europe’s future prosperity as well as for its security. Europe needs to better regulate technology transfer, and to come up with a clear strategy in regard to the coming battle over 5G technology.

Europeans may see their choice of options as unappealing, but in 2019, the European Union’s cautious fence-sitting may need to come to an end. As the deliberate ambiguity of the “China dream” unfolds, Europeans may be forced to ask themselves if their post-modern “European dream” of shared sovereignty and multilateralism can continue as great power competitive co-existence vies to reshape the contours of the world order.

In a supreme act of balance, the concluding performance of the Chinese New Year Gala at the Bozar theatre attempted to combine the traditional Chinese acrobatic talents of a male performer with those of a European-style ballerina who posed in toe shoes on the Chinese acrobat’s head. This dance metaphor of E.U.-China relations had the effect of looking painful as well as dangerous.

About the Author

Theresa Fallon is the founder and director of the Centre for Russia Europe Asia Studies (CREAS) in Brussels. She is concurrently a member of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific and a Nonresident Senior Fellow of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. In 2015-2016 she was a member of the Senior Advisors Group to the NATO Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.