At the recent G20 meeting in Sydney, representatives committed to increase growth by more than $2 trillion over the next five years through the adoption of ambitious and comprehensive structural reforms. However, research just released by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) suggests that while focussing on productivity and employment is vital for economic prosperity, so too are concerted efforts to increase peace.

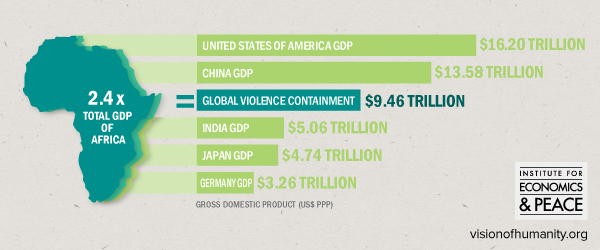

The Global Costs of Violence Containment report provides one of the first estimates of the economic cost of violence and the fear of violence to the world economy. It finds that violence, and attempts to prevent and protect against it, cost the global economy upwards of US $9.46 trillion per annum or 11 per cent of Gross World Product.

IEP’s research uses ten indicators from the Global Peace Index (GPI) and three additional key areas of expenditure to place an economic value on thirteen different dimensions of violence. From this, it found that military expenditure constitutes 51 per cent of total expenditure on violence containment, followed by homicides and police at 15 and 14 per cent respectively. Interestingly, it was also found that as countries became more peaceful they spent proportionally less on violence than their less-than-peaceful counterparts.

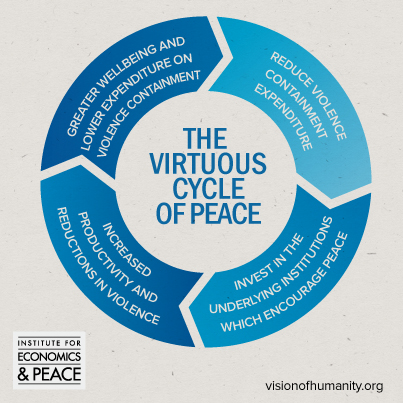

Although the findings provide a powerful illustration of the extent of economic activity related to violence, one of the most important insights is the benefits that could be obtained through government policies that promote and safeguard peace. Not only is excess expenditure in areas such as the military fundamentally unproductive, but by freeing up these resources more can be invested in activities such as health, education and infrastructure which encourage economic growth and improve wellbeing.

Consider, for example, a household that becomes fearful of violence. As an initial step they might decide to increase household expenditure by installing new locks or bars on their windows, thereby reducing the household income they have available for healthcare, food or education. In addition, the family may change how they travel to work or school to avoid areas they perceive to be risky, increasing travel costs. Consequently, higher levels of fear may result in more energy being devoted to maintaining safety, greater levels of stress and reduced productivity.

Similarly, the presence of fear is enough to impede innovation and employment creation through discouraging investment and the formation of mutually beneficial business relationships. Shon Hiatt and Wesley Sine followed 730 new business ventures to determine how they were impacted by political and civil violence. Their research found that not only did higher levels of violence reduce the success and survival of firms it also discouraged longer-term strategic planning. Yet, this is by no means a contemporary phenomenon. According to research undertaken by Ross Thomson the American Civil War may have sped up advances in firearms and shoe mechanization, but slowed innovation in petroleum.

Although it is not argued that benefits from technological innovations related to the military are insignificant, it is likely that a more peaceful environment would foster incentives for encouraging innovation in more productive ‘peace industries’. Given the capital intensive nature of the military it is also likely that moving expenditure to alternative uses, such as education will create more employment overall, a key priority identified by the G20.

Despite it being difficult to ascertain how such structural changes are likely to impact economic fundamentals, the evidence appears to clearly suggest peace as a powerful policy lever for the purposes of achieving growth, innovation and productivity. This was demonstrated in a more detailed report by IEP on, the G20 member, Mexico which found that not only were the direct costs of violence significant, accounting for more than 3.8 per cent of GDP, but that states in Mexico which were more peaceful in 2003 were also those which experienced the strongest economic growth over the next decade.

Globally this has also been found to hold, with IEP analysis suggesting that over the long-term those countries which improve peace also tend to achieve higher economic growth. Although it is a utopian vision to expect a world free of violence, peace clearly makes economic sense. For the G20 and the world more broadly much could be gained from broadening their consideration beyond economic growth alone.

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit research organization dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress.

For additional materials on this topic please see:

Pillars of Peace: Understanding the Key Attitudes and Institutions that Underpin Peaceful Societies

Strengthening the UN Peacebuilding Commission

A New Containment-Policy: The Curbing of War and Violent Conflict in World Society

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.