This article was originally published by New Security Beat.

A 20-year peace accord between Mozambique’s two major political parties was brought to an abrupt end last fall. A series of violent skirmishes between FRELIMO and RENAMO resulted in at least 10 deaths, dozens injured, and fears that the country might relapse into the kind of political violence seen during its civil war, which left more than a million dead. RENAMO claims its frustrations stem from a fraudulent electoral system and social inequality, but some observers have suggested their motivations may be less benevolent: making sure they get their piece of the country’s newfound natural gas wealth.

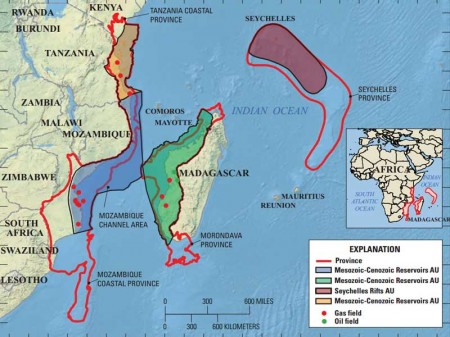

Long off limits due to limited technology, a grueling 16-year civil war, and Portuguese colonial rule before that, Mozambique’s hitherto untapped coal and hydrocarbon deposits are now available for foreign investment. Extensive coal mining has already resulted in rapid gross domestic product growth over the last decade, and international petroleum powerhouses Andarko (American) and Eni (Italian) plan to begin exporting liquid natural gas from Mozambique’s offshore deposits by 2018. But if the exploitation of these natural resources is to lead to broader socioeconomic development – almost 60 percent of Mozambique’s population makes less than $1.25 a day – RENAMO has a point in one respect: the government needs a deliberate multiuse natural resource management plan that goes further than naming potential socioeconomic benefits on paper and ensures the implementation of sound health policy and improvements in education at the local level.

A recent government investment in Mozambique’s tuna industry may indicate that FRELIMO does indeed plan to invest more in local job creation and socioeconomic development. According to a 2008 report by the Food and Agricultural Organization, Mozambique’s fishing sector employs 90,000 people. But 90 percent of these are in artisanal – small-scale or single family – operations. If managed justly, the development of a larger, more organized national tuna industry could increase the livelihood stability and economic prosperity for many of these people while keeping marine resource wealth within the country.

How the government balances the development of a national tuna industry and its offshore gas fields – which overlap tuna migration routes – will be an important test for the burgeoning coastal nation.

Can Tuna Thwart the Resource Curse?

The potential for major investment in the tuna industry came suddenly this September, when a new government-owned company, EMATUM, made headlines for issuing the country’s first ever USD-denominated bond: $500 million to support a national tuna fleet, which a French shipbuilder expects to deliver by 2016. A large portion of the bond has already helped purchase new vessels, and EMATUM has slated other portions of the bond for an operations center and related training, according to the bond prospectus.

Given FRELIMO’s track record – Mozambique was downgraded from an electoral democracy after the widely criticized 2009 presidential elections by independent watchdog organization Freedom House – a brand new company receiving a high profile investment may seem like evidence of corruption to some. “It does raise the question as to why the government would issue a government guarantee for this size to a fairly unknown government agency in the fishing industry while there are a large number of other perhaps more constructive projects with a higher return in that economy,” Standard Bank’s Yvette Babb told Reuters. According to a report from Bloomberg, there’s also evidence that the patrol boats may ultimately carry arms, which apparently was not explicit in the prospectus for creditors.

But despite how it looks, the abrupt investment may not be nefarious, according to David Michel of the Washington, DC-based Stimson Center. Rather, it may be a real sign that Mozambique is serious about capitalizing on one of its few comparative advantages in the global economy.

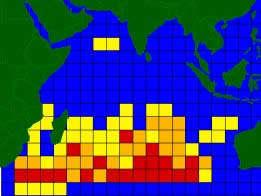

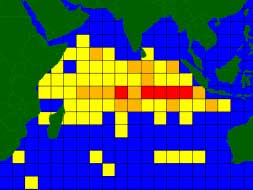

According to Mozambique’s 2012 National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, almost 6,000 metric tons of tuna were reported caught off the coast in 2011 (comparable to reported catch off the United States’ Atlantic coast in the same year), and climate change studies suggest East Africa’s catch potential may increase in the next few decades. But only foreign fleets currently receive licenses for tuna fishing in Mozambique’s exclusive economic zone, sending most of the value added from tuna products to ports overseas. The bond’s new vessels could provide local employment, while the operations center and new strategic plan encourage fleets to land catch from domestic waters in local ports, enabling Mozambique to add value to their tuna products before exporting. Finally, the purchased patrol vessels – armed or not – could also improve enforcement capacity and curb losses from illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, which costs tens of millions of dollars annually.

If tuna contributes significantly to the national economy, the industry could also help Mozambique avoid the “resource curse,” as it is commonly called – a phenomenon in which natural resource exploitation in developing countries results in instability, corruption, and poverty rather than improved quality of life for local citizens. Tuna fishing is an industry in which many Mozambicans already have the skill and expertise to contribute, unlike natural gas extraction. As long as there are fish in the sea, it could be a healthy addition to what would otherwise be a hydrocarbon- and coal-dominated national economy.

Scarcity, Offshore Drilling Are Potential Hurdles

The caveat is “as long as there are fish in the sea.” Even if EMATUM uses the national tuna industry for equitable socioeconomic development, fish may not prove the most stable investment.

Global population and consumption growth alongside technological improvements have put unprecedented pressure on fish stocks worldwide since the 1950s. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists three of Mozambique’s most common tuna species – Albacore, Yellowfin, and Bigeye – as near threatened or vulnerable to extinction with declining populations. David Michel noted that one important metric – tuna catch per unit of effort – has been highly variable in the Indian Ocean over the past decade, providing inconsistent revenue for fishermen. Even if changes in sea water temperature or upwelling patterns cause regional increases in total catch potential, variability may still threaten the industry’s stability. Consistent monitoring, sustainable catch quotas, and an ability to enforce foreign compliance to regulations will be essential to long-term viability.

The ongoing development of natural gas reserves may also shake things up. Most of Mozambique’s discovered hydrocarbon resources are offshore, and the infrastructure needed to extract and export them, such as dredging for pipe-laying, will change aspects of the physical coastline, while prospecting for new fields could affect tuna migration. Andarko’s environmental impact assessment for the exploration phase notes that seismic testing affects commercial artisanal fishermen through “temporary loss of access to fishing grounds” and “temporary decreased catch volumes” and documents “several sightings” of schooling tuna during surveying, but the impact assessment for the extraction phase only mentions future exploration activities as part of the cumulative impact assessment. Australian and Namibian tuna fishermen have recently complained about similar seismic testing for oil and gas exploration disrupting tuna migration and drastically reducing catch rates, with Namibian fishermen pushing the government to ban it during the spring migration season. In Mozambique, tuna fishing occurs year-round but peaks throughout the first six months; similar measures would ask oil and gas companies to put exploration on the bench for half the year.

If the coal industry is anything to go on, provincial governments may struggle to anticipate and resolve such conflicts between local citizens and extractive industry. According to the Mozambique News Agency, botched resettlements of villagers moved off their land for coal mining have created anxiety among some coastal communities about natural gas extraction. A recent consultation with a village making way for the construction of the world’s second-largest liquefied natural gas plant resulted in a shouting match between community members and provincial government officials. Villagers accused the government of planning to relocate them 50 kilometers inland – a legitimate concern when most rely heavily on subsistence fishing. The government denied any such plans.

A Hazy Horizon

The recent clashes between FRELIMO and RENAMO highlight the crossroads at which Mozambique stands. Economic growth, largely from massive coal extraction, has failed to relieve millions from poverty. The country consistently ranks in the bottom five of the annual Human Development Index, and while many of its neighbors have seen declines in total fertility rate – the average number of children born per woman, an

important indicator of reproductive, child, and maternal health – Mozambique’s has climbed since the end of the civil war in 1992. The result is a rapidly growing, disproportionately young population with almost no employment prospects or financial security and dwindling trust in the government.

The abundance of natural resources and recent foreign investment interest has given political leaders renewed hope for a better future. States like Norway could be models for peaceful, multiuse coastal management efforts, while regional neighbor Botswana proves that developing countries can avoid the resource curse.

But questions remain: Can the tuna and natural gas industries thrive at the same time, or will one simply win out over the other? What are RENAMO’s ultimate interests, and will they voluntarily accept a return to peace? Can a FRELIMO-led government muster the political will and capacity to shape national policy effectively and utilize natural resource wealth equitably? As Mozambique’s global prowess grows, the answers to these questions could be a bellwether for future growth or a return to instability.

Sources: AllAfrica, African Development Bank Group, Andarko, BBC News, BDlive, Bloomberg, Fish Info and Services Co. Ltd, Global Forum on Agriculture Research, The Guardian, Guernica, ICF International, IRIN, Libération, Marine Resources Assessment Group Ltd, The New York Times, ReliefWeb, Stimson Center, The Sydney Morning Herald, UN Development Program, UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, UN Population Division.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

A Boom for Whom? Mozambique’s Natural Gas and the New Development Opportunity

Small-Scale Fisheries in Mozambique

Renamo’s War Talk and Mozambique’s Peace Prospects

Social Reform and Economic Transformation in Mozambique

Balancing Development and Coastal Conservation: Mangroves in Mozambique

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.