Steven Pinker, one of the world’s leading academics in peace and conflict studies, provides a sweeping summary of the history of violence and conflict since 10,000BCE in his book ‘The Better Angels of Our Nature’. Using a wide array of case studies, historical evidence and statistics, Pinker concludes that, contrary to popular perceptions, since the dawn of civilization the world has become increasingly less violent.

For instance, the research of Manuel Eisner suggests that during the Middle Ages the rate of homicides in Europe lay somewhere between 20 to 40 per 100,000 persons, while in modern times estimates place the rate closer to 1 per 100,000. Similarly, we know that deaths relating to war have been trending downwards since 1946 as a consequence of a reduction in interstate and international armed conflict.

In contrast, the Global Peace Index (GPI), the world’s pre-eminent measure of peace, suggests that this trend may not necessarily continue. This year’s Index records a decline in global peace since 2008, overturning a 60-year trend dating back to the end of the Second World War.

This recent trend has been driven predominately by deteriorations in internal peace indicators, especially those relating to safety and security. Key indicators that deteriorated over this seven-year period are levels of terrorist activity, the homicide rate, the likelihood of violent demonstrations, levels of organized conflict and perceptions of criminality.

So is the world becoming more or less peaceful?

That depends on how you define peace. Professor Johan Galtung, who is considered the father of peace studies, has spoken of the anger he felt as his daughter told him how fearful she was of nuclear weapons, during the height of the Cold War. Peace, it seemed, was more than just the occurrence of violence, but also the fear of it.

Recognizing this, the Global Peace Index defines peace as the ‘absence of violence or the fear of violence’. Consequently, although Pinker’s work complements that of the Institute for Economics and Peace, he is measuring violence while the Global Peace Index measures peace. In addition, the two measures focus on different time periods. In particular, the Global Peace Index, having been established in 2007, measures short-term trends in peace, whereas the work of Pinker and the Human Security Report focus on the long-term.

In addition, the Global Peace Index is multidimensional in attempting to gauge levels of peace. Its 22 quantitative and qualitative indicators are organized into three sub-domains: Ongoing Domestic and International Conflict, Militarisation, and Societal Safety and Security. The argument is that low crime rates, minimal terrorist activity and violent demonstrations, harmonious relations with neighbouring countries, a stable political scene, and a small proportion of the population being internally displaced or made refugees can be equated with peacefulness.

Seven further indicators are related to a country’s military build-up—reflecting the assertion that the level of militarization and access to weapons is directly linked to how peaceful a country feels, both domestically and internationally. Comparable data on military expenditure as a percentage of GDP and on the number of armed service officers per 100,000 people are factored in, as are financial contributions to UN peacekeeping missions.

But how do we know that peace is declining?

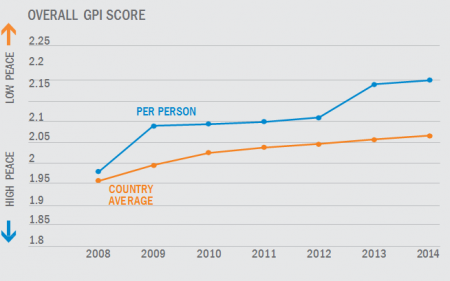

This year, IEP used two methods to determine average peacefulness since 2008. In the 2014 GPI a ‘country average’ and a ‘per person average’ of global peace were calculated covering the period since 2008. The results of the two methodologies were compared to determine whether there were differing trends. Both sets of results show the same overall trend, strengthening confidence in the statement that the world has become less peaceful in the past seven years. This has been illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Global and Per-Person Trends in Peace (2008 to 2014)

Both methods of calculating the global change in peace show the same trend, indicating the world has become less peaceful

Although some of this is a result of the high visibility and devastating impact of certain violent events since the beginning of the 21st century, it appears clear that although there is less violence over the longer-term, in the last 7 years the world has become less peaceful.

In addition, these global decreases in peace have not been evenly distributed, with there being a tendency for declines in peacefulness to be concentrated in nations with the lowest levels of economic and human development. That is, although we may be living in some of the most peaceful times in history, that trend is not certain to continue throughout our lifetime, and the benefits of peace are not equally shared as recent declines in peace have been borne disproportionately by poorer nations.

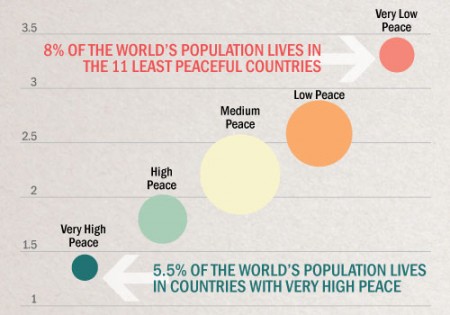

Figure 2: Global Peace Inequality

Globally the distribution of peace is highly unequal with 560 million people living in the 11 least peaceful countries

Put another way, the global distribution of peace and violence is uneven. For instance, although long-term global homicide rates have declined, as many as 900 million people, or 13 per cent of the world’s population, still live in nations with homicide rates close to the average in Europe 500 years ago. This means that while the long-term trend towards lower levels of violence is encouraging, its benefits have not been equally shared.

When it comes to peace, IEP’s research consistently shows that the absence or frailty of peace-supporting institutions can make a society more vulnerable and less resilient to shocks. In fact, analysis of peaceful societies found that in order to reduce violence and encourage peace, certain institutional ‘Pillars of Peace’ are essential. These were found to include:

• A well-functioning government;

• A sound business environment;

• An equitable distribution of resources;

• The acceptance of the rights of others;

• Good relations with neighbours;

• The free flow of information; and

• High levels of education; and

• Low levels of corruption.

While recent research suggesting that humanity is becoming less violent is encouraging, this progress must be continued. In fact, a range of research by IEP and other scholars suggests that improvements in peace are not accidental but within our control. Although humanity appears to have made great strides against violence (on average) much can be said about continuing to build on its foundations – that is, the structures, attitudes and institutions – that make societies peaceful.

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit research organization dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.