This article was originally published by the IPI Global Observatory on 10 April 2015.

It is now 17 years since the Good Friday Agreement brought what seemed to be a definitive end to the decades-long sectarian crisis in Northern Ireland. But, in a case that has repercussions for other peace processes such as Israel-Palestine, one of the architects of the agreement says there is still much work to be done before a line can be drawn beneath the conflict once and for all.

As a Methodist clergyman working with Loyalist groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force, Reverend Gary Mason played an important role in the processes of deescalating conflict in Belfast and across Northern Ireland.

Speaking with International Peace Institute Senior Adviser for External Relations Warren Hoge, Mr. Mason called the 1998 Good Friday Agreement a “masterpiece in political compromise,” but said it nonetheless had a number of missing pieces that are still being addressed. These include addressing controversies over flags, emblems, and parades by different groups.

“But the biggest story there is dealing with the past,” he said. “That’s going to be a key component—defining victims, looking at the whole concept of people who were involved in the violence. Should they be prosecuted? Should they not be prosecuted?”

Mr. Mason said it had realistically taken about 20 years to sow the seeds of the Good Friday Agreement, starting with the hunger strikes of 1981. While the approach to finding peace in Northern Ireland could not be a “panacea,” it might act as an example for other long and protracted peace processes, such as that involving Israel and Palestine, which hinged on similar issues of land, identity, and religion.

“There’s a lesson of talking to your enemies, that sometimes during conflict, you have to talk to people with whom you disagree and actually dislike and probably hate as well—that’s an important component; to understand the other person,” he said.

Mr. Mason’s commitment to creating peace extends to work done through his conflict resolution group Rethinking Conflict, and involvement in the Skainos Project, which is said to be the largest faith-based redevelopment project in Western Europe.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Listen to the interview here.

I first knew you back in the late 1990s, when I was covering the Northern Ireland peace process for the New York Times. So Gary, it is heartening for me to welcome you to the International Peace Institute as an old friend.

The first thing I want to ask you about is peace processes. The world thought that things were settled back in 1998, but that’s not the case, is it?

I’ve often said, Warren, the Good Friday Agreement was a masterpiece in political compromise, but it was incredibly difficult to get there. I’ve often quoted Jonathan Powell’s wonderful book entitled Great Hatred, Little Room, which primarily was saying the hatred between those two communities was intense, and there was little room for negotiation and getting them over the line.

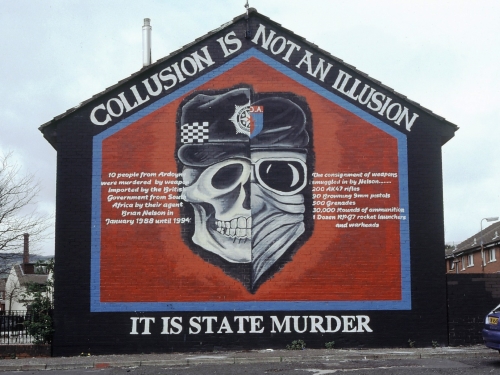

So it was a masterpiece in political compromise, but there were bits missing, with the result that we’ve had the St. Andrews Agreement, and just recently we’ve had the Stormont House Agreement. These address major components most commentators would say were missing from the process. These include dealing with flags and emblems, which are incredibly controversial, and the long running historical controversy around parades. It’s not a new phenomenon. There’s been controversy in parading within Northern Irish society from the 19th century, so it’s not a new phenomenon. But the biggest story there was dealing with the past, and that’s going to be a key component—defining victims, looking at the whole concept of people who were involved in the violence. Should they be prosecuted? Should they not be prosecuted?

So that’s a major aspect as we sit here in the early spring of 2015—that’s going to be a five-year-plus protracted process to see how we deal with the past, and there are a multiplicity of different committees that have been set up to look at that in some immense detail.

You’ve told me that there are five major steps in the post-conflict, consensus-building process. Can you run through them for me?

I would say that this is not an overnight phenomenon, it does take time, and one of the first concepts is engagement—there needs to be dialogue, there needs to be conversation. We need to integrate people rather than alienate them. You also need to be wise in looking for potential spoilers, and if you believe there are spoilers there, the key is to bring them inside a tent rather than outside.

The second kind of concept is what we would call sort of reframing—understand that at times your enemy may reframe your actions to look victorious, and that allows flexibility as people move towards peace, so that allows both sides to really frame or reframe the compromise as a victory without having to denounce the past.

We also need, thirdly, internal agents of change, so that can be former prisoners, people that were held up almost as icons of guerilla warfare, who eventually—rather than speaking the language of political violence—are now saying it’s political compromise, it’s political negotiation. Republicanism was a classic example of that, where for many years it was an arms struggle. Come the 1980s, it became the ballot box in one hand and the Armalite in the other, and then the evolution took place where by the early 1990s they knew they were going to move towards a political strategy, and eventually for all of us a political compromise. It’s also important to involve external critical friends.

A lot of my role has been that I be classed as the main critical friend to the Ulster Volunteer Force—that’s understanding their ethos, their ideology, what has shaped them, but also having the ability to present alternatives, options, ways to move forward, while not denying the rock they were hewn from. That’s another key component.

The fourth aspect is developing the community around some of those combatants. At the moment, the Ulster Volunteer Force have a program called ACT, which is Action for Community Transformation, and it’s really based around the principle of DDR, which many people use in peace processes and that would be the whole aspect of demobilization, then decommissioning, and then the messy bit of reintegration. I’ve often said if you lock 40 men in a room, listening to their own reassuring voices, it really is a recipe for disaster. So what’s the role of civil society in that reintegration process? That means walking closely with many people who have been involved in violence.

And the fifth thing—which does not help us Westerners who want everything done overnight, we’re an instantaneous generation—is that peace processes take time in reality. The seeds of the peace process were really probably sewn during the hunger strikes of 1981 despite that painful time when people were beginning to struggle and say, “Are there alternatives? Are we condemned to pass this painful conflict to generation after generation?” So really it nearly took another 20 years before the seeds emerged of the Good Friday Agreement.

You’ve worked with a particularly difficult population, the so-called Loyalist fighters, who believe that armed struggle was the only way they could secure their objective, namely to make sure that Northern Ireland remain part of the United Kingdom and not break away as the Republican movement wished, and one day become part of Ireland.

I remember, though, that the most grizzled of these former fighters used to tell me that they wanted to work now to spare a new generation the conflict that they had pursued with violence. Have the former fighters taken the lead in recasting their communities in a more constructive direction?

I think there’s no question about it both within Republicanism and within loyalism. The people who, to put it quite bluntly, do have blood on their hands have taken the lead, and taken immense risks. Sometimes it has been mainstream politicians, to be quite honest, who have been the most difficult people to actually bring along. In reality, many of these people didn’t have to risk their political career. They were former militia or paramilitaries or freedom fighters or terrorists—people will use different phrases to describe them. But I think the people that saw the pain—for example, some of these people were sleeping in different beds every night primarily because they were on the hit list of the other side—and realized, “I don’t want to pass this pain to another generation.” So that was a major, major issue that a number of these men—and they were primarily men that were involved in that conflict—realize we can’t pass this pain to another generation, we need to draw a line. The well-worn phrase is, “I believe that we’ve finally taken the gun out of Irish politics.”

A wonderful church leader of another generation once said in a religious context that, “too many people in our churches do not have guns in their hands, but they most certainly have guns in their hearts.” So that’s the next aspect of this—it’s decommissioning people’s minds, because in reality it was a mindset that brought this conflict about. As a Jewish scholar once said, “Dehumanization precedes genocide,” and there’s no question about it, both Catholics and Protestants have this sad ability to dehumanize one another.

You used the word “decommission” just now, which means something in Northern Ireland. It doesn’t mean too much to people who don’t know the situation there. I think it was George Mitchell’s idea, the broker, who came up with the phrase “decommission” because nobody wanted to disarm. Disarmament meant surrender and neither side was going to do that. Decommissioning sounds like shuffling papers around, and I always thought that was a brilliancy of the process that he came up with. So decommissioning, which you mentioned before became a very big issue, it meant disarming, but they didn’t have to use that word and that’s why in the end they didn’t.

You talked about the two sides, of course, but I’ve noticed you’ve also written something that you call The Role of Intra-Group Consensus-Building in Disarming Militant Groups in Northern Ireland. That’s talking about interior things, your own group, your own co-sympathizers. What did you mean by the dangers of having conflict within your own group as opposed to from the outside?

In moving towards any peace process, people who have been involved in paramilitary activity or militia activity want to believe what they fought for, they won—you know, major sacrifices have been made. Family members have died, people have been displaced—people want to believe that they won. So the whole process that takes place within these groupings is crucial, so there would have been no sense for the Republican movement, the IRA, or the UVF, or the Ulster Defense Association signing up to something if the majority of their people were not coming with them. So for example, the UVF, I worked extensively with. They would have been seen as the most lethal kind of Protestant paramilitary group during the conflict. They did their decommissioning statement in my church building in the last Saturday in June in 2009 [11 years after the Good Friday Agreement], and it was a great day.

Again, that Western mentality of overnight phenomena does not take place in peace processes. It was a day when I was emotional. I think there weren’t too many tears, but I gulped a couple of times as I swallowed that emotion in my throat as I heard that statement finally read out. Phrases like, “weapons beyond reach,” or, “weapons beyond use,” were also put in, but there was no humiliation—there wasn’t a bully boy bouncing on top of someone making them give up their weapons. This was an internal process.

What the UVF did was they had two years of road shows where they basically went around to their grassroots members to secure their vote to move towards decommissioning. So when the paper was finally read out in my church building in 2009, people were on board, because the last thing you wanted was a multiplicity of terrorist groupings who were not on board maybe starting the conflict in a different way.

The Northern Ireland peace process is a fascinating process and I’m learning through you right now, it continues on and continues to be fascinating, and it may be even more important now to build consensus than it was before it actually happened. What application does the Northern Ireland peace process have for other peace processes? I’m thinking in particularly of the Middle East.

I’ll say first of all that it’s not the panacea for the world’s ills. But I think it does say to people that have been involved in long protracted processes that there can be certain mechanisms or processes adapted that may, and I underline the word “may,” allow a way forward. There’s a lesson of talking to your enemies, that sometimes during conflict, you have to talk to people with whom you disagree and actually dislike and probably hate as well—that’s an important component; to understand the other person.

I remember doing a lecture in Tel Aviv in March of ’14, and someone in the audience challenging me, and almost kind of pooh-poohing my theory of the peace process in Northern Ireland being applicable, and I just simply asked this person one question, “Would it be fair to say that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is about land, about identity, and about religion?” He obviously replied, “Yes.”

And the Irish process did involve land, and most certainly did contest space. It did involve identity: Am I British, Irish, Northern Irish? Who am I as a person? While it was not a religious conflict, it must be said—and I say this quite clearly as a person of the faith—the Christian church unfortunately has contributed to a multiplicity of conflicts across this globe. There’s absolutely no question about that, so the roots of religious sectarianism were born in the 16th and 17th century, and I’ve often used the phrase that the, “fertile soil of religious sectarianism was alive and well in Northern Ireland.”

And even as I look at the United States at the moment at areas like racism and even look at South Africa, I think it’s important to say the Dutch Reform Church were the people who propped up apartheid using theology, so religion can be toxic. I think we need to be careful how we use religion because it can be a very destructive mechanism and that happened in the Irish peace processes, as it is happening in the Middle East processes, this concept of “god is on my side,” which means he’s definitely not on your side. That’s a very dangerous, dangerous mantra to be using.

I left Northern Ireland in 2003 and I went there more than a hundred times between 1996 and 2004, and it was a profoundly changed place. What had been dark and forbidding, downtown Belfast, had become a place that people throughout the British Isles sought out on the weekends to have a good time.

But also the people were ahead of the politicians. The politicians by that point had not created the political structures, but the people had realized the killing is over, we’re not going to go back to that, and move forward. Yet still I remember that all those hatreds you’ve mentioned were still pretty much intact. If I go back now would I find a bit of a different dialogue between the two sides than I found 12 years ago?

I think by and large the middle classes to a high degree have bought into the peace process on both sides. I think the leadership of Republicanism has also done a major job in moving people within Republicanism—within working class areas—forward. My major concern would be the Loyalist community, which I worked with now for three decades of my life by choice, spending time working in the inner city.

I think in many ways the Loyalist community was not prepared the same way for the Good Friday Agreement as the Republican community was, and so I still think there’s a major piece of work to be done within loyalism. I think it’s also very important to say that loyalism contributed immensely to the peace process and I think sometimes that can be forgotten. This was not a one-sided tool, and I pay tribute to those within Republicanism, but it wasn’t just Republicanism that brought peace to that island, many strategic people within Loyalism also brought peace, and I know president Bill Clinton in his last visit to Northern Ireland there in Derry on a pretty cold March day, he made a speech there in the square at the Guildhall and said, “There still is unfinished business,” and there’s a lot of items of unfinished business. One of those items of unfinished business is allowing Loyalism to feel confident, but also to feel at peace with itself, and I think that is something that all of us need to address.

You mentioned before these two or three recent agreements getting over some new stumbling blocks. Can the spoilers still ruin this thing? Is it now secure enough that we can go forward with incidents occurring, but that the momentum will not be reversed?

I would believe that while there are some spoilers out there, there are still a number of dissident Republican groups—and in the last few years people have lost their lives because of their terrorist activity—there’s not the momentum. I think by and large now, the vast majority of people want to see a Northern Ireland that’s at peace with itself. Relationships have been transformed between Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, all the ministerial bodies that have been put in, visits by the Queen to Dublin, the Irish president to London—so relationships are changing and so hopefully the days are gone when people will feel we need to get one over on each other.

But still, I want to say we need to be careful. Peace is a very precious commodity. It’s a relationship with people, and like any relationship it needs to be worked at, it needs to be nurtured, it needs to be hugged and kissed on the right occasions.

I was just thinking the last time I saw you we were in your East Belfast parish, nearby there were people flinging things over a wall from the two communities. It’s nice to see you here all these years later in a more peaceable setting, but it’s particularly great to know you were so engaged with this process for which you can take so much credit and that you are nurturing it, and taking care of it, and pushing it forward. Thanks so much for coming to the Global Observatory.

Thank you, Warren. Great to see you again.

Warren Hoge is Senior Adviser for External Relations at the International Peace Institute (IPI).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.