This article was originally published by New Security Beat, a blog run by the Environmental Change and Security Program of the Wilson Center, on 12 May 2015.

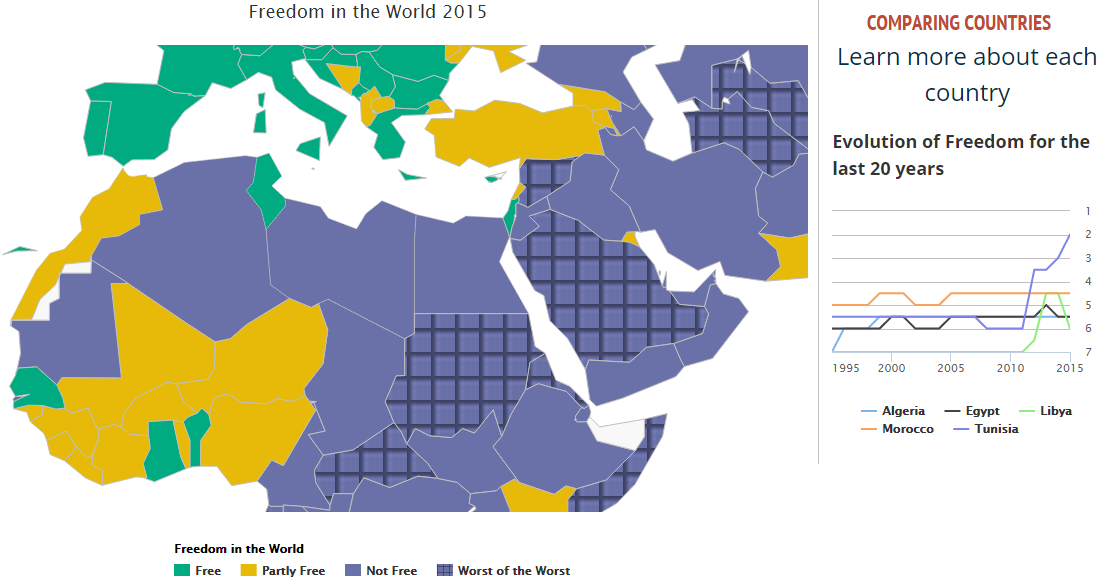

Among the few bright spots in the 2015 Freedom in the World Report, the brightest may be Tunisia, which for the first time was assessed as “free” – Freedom House’s highest “freedom status” and for many political scientists the definitive indication of a liberal democracy. Tunisia is the only North African state to have been assessed as free since Freedom House began its worldwide assessment of political rights and civil liberties in 1972, and only the second Arab-majority state since Lebanon was rated free from 1974 to 1976.

Tunisians have had little time to celebrate. A deadly raid by jihadists on Tunis’ Bardo Museum on March 18 left 20 foreign tourists and 3 Tunisians dead and has led several analysts to warn that Tunisia’s fledgling democracy is at serious risk.

The threats, analysts contend, reach well beyond sporadic jihadist violence and the proliferation of weapons from Libya’s civil war. They include the eventual return of several thousand young Tunisians from wars in the Middle East, inequities between the country’s cosmopolitan urban north and its clan-conscious rural south, remnants of Ben Ali’s regime in the security sector, and hardliners that could ultimately nudge out moderate leaders in Tunisia’s main Islamist party, Ennahda.

What chance does Tunisia’s democracy have of withstanding these formidable challenges? Surprisingly, a good chance, according to recent research in political demography, a field that is focused on a limited yet robust set of relationships between demography and political outcomes.

The Age-Structural Model

In 2008 and 2009, two articles called attention to the potential rise of “one or more liberal democracies” in coastal North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt) between 2010 and 2020. These articles drew upon the work of a small, unclassified National Intelligence Council research program on political demography, which experienced its heyday between 2006 and 2009.

That forecast relied on what may seem to most political analysts as an unconventional source of evidence: the maturity of a country’s population age structure. In the April issue of the Journal of Intelligence Analysis, I encourage intelligence analysts to step out of historical time – the time we all live in and historians write about – and instead analyze political conditions and predict trends and events in the domain of age-structural time, a scale measured in years of median age (the age of the “middle person,” for whom half of the population is younger).

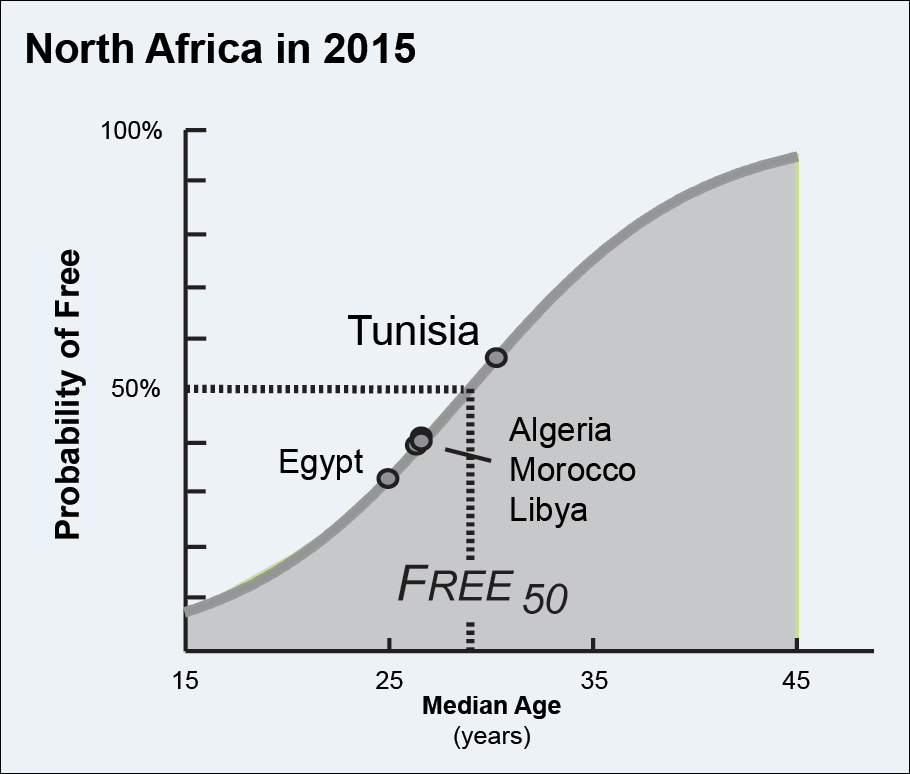

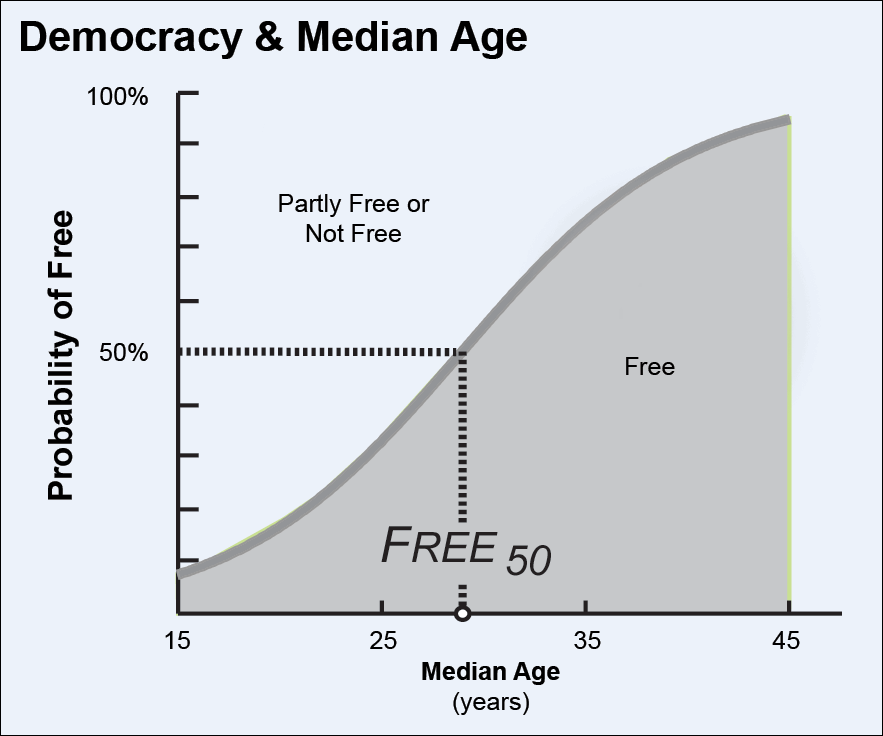

Why this alternative scale? Because democratization is statistically sensitive to it. As median age increases – as it has in most parts of the world over the last century – so does the likelihood of being assessed as free (Figure 1). In addition, the scale facilitates forecasts. Because the UN Population Division revises its rich set of demographic scenarios biennially, plausible projections of median age are available for several decades into the future.

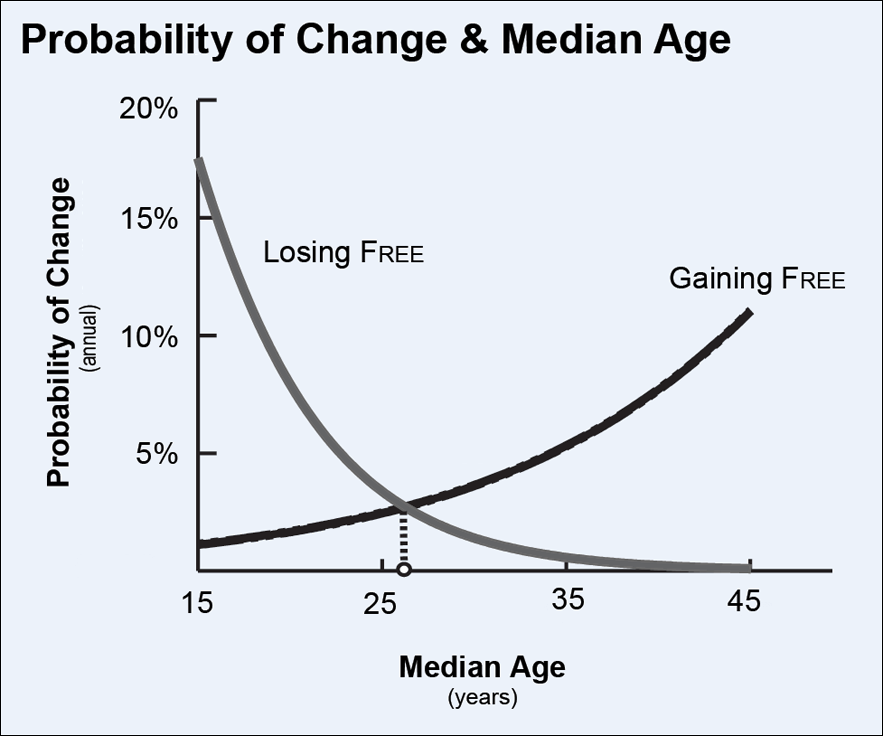

Few youthful states have attained liberal democracy, and most of those have lost it within a decade (Figure 2) – a conclusion that should make development policymakers doubly cautious about coaxing youthful countries into high levels of democracy.

Since the initial articles stemming from research at the National Intelligence Council, others have called attention to the rise of high levels of democracy among age-structurally mature states and the fragility of youthful democracies. These relationships have been the focus of articles by Hannes Weber in Germany, by Timothy Dyson in the United Kingdom, and by myself and John Doces in the United States. Despite differing approaches, all the authors arrived at very similar conclusions.

Tunisia’s Chances

From political demography’s statistical perspective, Tunisia is far from the anomaly that Middle East analysts too often portray it to be. The country’s political transition was similar, in age-structural timing, to ascents to liberal democracy in southern Europe in the 1970s (Portugal, Greece, Spain), in East Asia from the late 1980s to the early 2000s (South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia), and in Latin America more recently (Chile, Brazil, Argentina).

Of the 62 declines from free status recorded in Freedom House’s data, the vast majority have occurred among states with a median age less than 26 years. Among states, like Tunisia, that have been assessed as free at a median age of 30 years or older, declines to a lower status have been infrequent. Since 1972, Freedom House records only three such declines: Thailand, which lost free status in 2005 and has since declined to “not free” (Freedom House’s lowest freedom status); Latvia, which declined from free for only two years (1992-93) shortly after independence; and most recently, Ukraine, in 2010.

With its median age just over 31 years, the age-structural model estimates Tunisia’s current annual risk of losing Freedom House’s free status to be very low (less than two percent). If Tunisia can avoid the pitfalls of major conflict and bad neighbors, the persistence of Tunisia’s liberal regime over the next two decades would not at all be surprising.

Could there be short interruptions? The model cannot say. At their peak in 2007, liberal democracies represented just 40 percent of the world’s 166 independent states with populations over 500,000, limiting both sample size and the certainty of such specific predictions.

Right on Time

Criticisms of this forecast are not difficult to anticipate. Some Middle East analysts are likely to argue that Tunisia’s democracy is but a fleeting remnant of the Arab Spring. The age-structural model paints a very different picture. Since the model’s first trials in 2007, it has pointed to Tunisia as the most likely of all Arab-majority states to attain and maintain liberal democracy.

It still does. According the UN Population Division, Tunisia passed the point where the model gave the country a 50 percent probability of being a liberal democracy (28.9 years, a median age that I call “Free50”) in 2010. Morocco, Algeria, and Libya are projected to reach that benchmark in 2020, while for Egypt, Free50 lies close to 2030. Only two other Arab-majority countries are scheduled to hit that benchmark before 2025: Lebanon already passed the markin 2011, and Bahrain is projected to pass Free50 in 2022.

Other critics will argue the geopolitical situation sets the rise of Tunisia’s democracy apart. They would be correct to remind us that today’s democracies in southern Europe, East Asia, and Latin America stabilized during the regional decline of communist influence and after downturns in political violence. In contrast, jihadist violence and organized political Islam appear on the upswing.

Admittedly, that criticism is particularly hard to rebuff. Because statistical models are built on a body of past data, they are understandably vulnerable to future conditions that are distinctly different from the past, and to new cases that are deeply dissimilar from the pack of prior cases. I assume, in order to apply the age-structural model to Tunisia’s case, that the past will be like the future and this case is within the behavioral range of prior liberal democracies.

These criticisms, as well as the age-structural model’s forecasts, should be viewed as alternative hypotheses to be tested as Tunisia’s political future unfolds. The ultimate outcome, whatever it may be, will be used to adjust the model.

Leave Nothing to Chance

Tunisia’s democracy, however, owes nothing to statistical models or to the probabilities they generate. It was built on Tunisians’ own tenacity and sacrifice. For many reasons, it would be a terrible loss to Tunisians, as well as to the future of the region, if the world’s newest liberal democracy were to suddenly slip away.

Therefore, it would be unwise for policymakers in established democracies (or for analysts like me) to downplay the serious challenges facing Tunisia’s regime. Nonetheless, the age-structural model’s forecasts are clearly quite positive. It would be equally unwise to underestimate Tunisia’s readiness for a long future of stable liberal democracy.

Richard Cincotta is a Wilson Center Global Fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington, DC.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.