Image courtesy of Kurious/Pixabay.

This article was originally published by Geopolitical Futures on 19 October 2017.

Blending the policies of his predecessors, the Chinese president is trying to liberalize with an iron fist.

The world has changed since modern China was founded, and it seems that China, not for the first time, is changing with it. When Mao Zedong established the republic in 1949, having fought a civil war to claim it, China was poor and unstable. To reinstate stability he ruled absolutely, his government asserting itself into most other state institutions. Private property was outlawed, and industrialization was mandated, from the top down, in an otherwise agrarian society. The goal was to disrupt China’s feudal economic system that enriched landlords but left most of the rest of the country in poverty. Mao’s techniques ensured compliance with government policies, but they did little to improve the country’s underdeveloped economy. This is what we consider the first era of communist rule.

When Mao died in 1976, his successor, Deng Xiaoping, made economic development his utmost priority. He liberalized some of Mao’s policies, allowing foreign trade in some areas and private ownership in others, and so ushered in the beginning of China’s economic miracle. The country prospered, but it did so unevenly. The coastal provinces became wealthy while the impoverished interior regions floundered. Liberalization meant less government control, but with less control, military and economic elites began to pursue their own interests, which sometimes ran counter to those of the party. Central leaders became comparatively less important. This is what we consider the second era of communist rule.

The third era of modern China may well have begun on Oct. 18, the first day of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party. President Xi Jinping basically said as much in his opening speech, noting that he would raise his country’s influence abroad and lower its poverty rates at home. To do that, however, Xi believes he must blend the policies of Deng and Mao – in other words, he must liberalize with an iron fist. This explains why, over the past five years, he has steadily accrued more power than almost any other leader, using anti-corruption as pretext to purge his political enemies. He has disciplined several party figures and replaced them with officials loyal to him. He has implemented a variety of military reforms. And he has centralized economic management more than it already had been – something he believes is necessary to remove the biggest impediments to Chinese growth and stability: uncontrolled maritime territory and an imbalanced economy.

The Protection of Rights

The Chinese economy depends heavily on exports, but the country’s geography is all but hostile to land-based trade. It therefore relies heavily on the world’s sea lanes to bring its wares to market. One of China’s geopolitical imperatives – something it must to do survive and thrive – is to guarantee trade through the East China Sea and South China Sea, areas to which Beijing has laid exclusive claim. (Nearly 40 percent of China’s total trade in 2016 transited through the South China Sea, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.) Put simply, these waters are so important to China’s economy that Beijing cannot afford to lose them. The government is aware of how vulnerable this dependence makes the country, and it is likewise aware that the United States, the world’s foremost naval power, could exploit it if a conflict between the two broke out.

One way to overcome this weakness is to overhaul China’s navy and air force. This is why, in his Oct. 18 speech, Xi said China intends to fully modernize its military and enhance the nation’s defensive capabilities by 2035. The stated rationale is to protect maritime rights and to engage in counterterrorism, disaster relief, peacekeeping and humanitarian relief. But the tacit reason is to protect its own maritime rights.

Some reforms are already underway. In 2014, for example, Xi reduced the number of military command regions from seven to five, and all armed forces were placed into joint groups to better coordinate their operations. Earlier this year, the People’s Liberation Army announced that it would cut 300,000 soldiers because modernization requires technological applications, not manpower. The central government is asserting dominance over the PLA and preventing alternative centers of power from arising. This, coupled with an increasing defense budget with a heavy focus on technological upgrades, will remake the armed forces into a more effective, modern fighting force.

Money to the Middle

History tends to repeat itself in China. Over the centuries, when Beijing opened up its economy, it generated wealth that usually never made it in to the rural interior provinces. The disparity created enough of an economic imbalance between the rich coast and the poor interior that the government needed to turn inward to reunite the country.

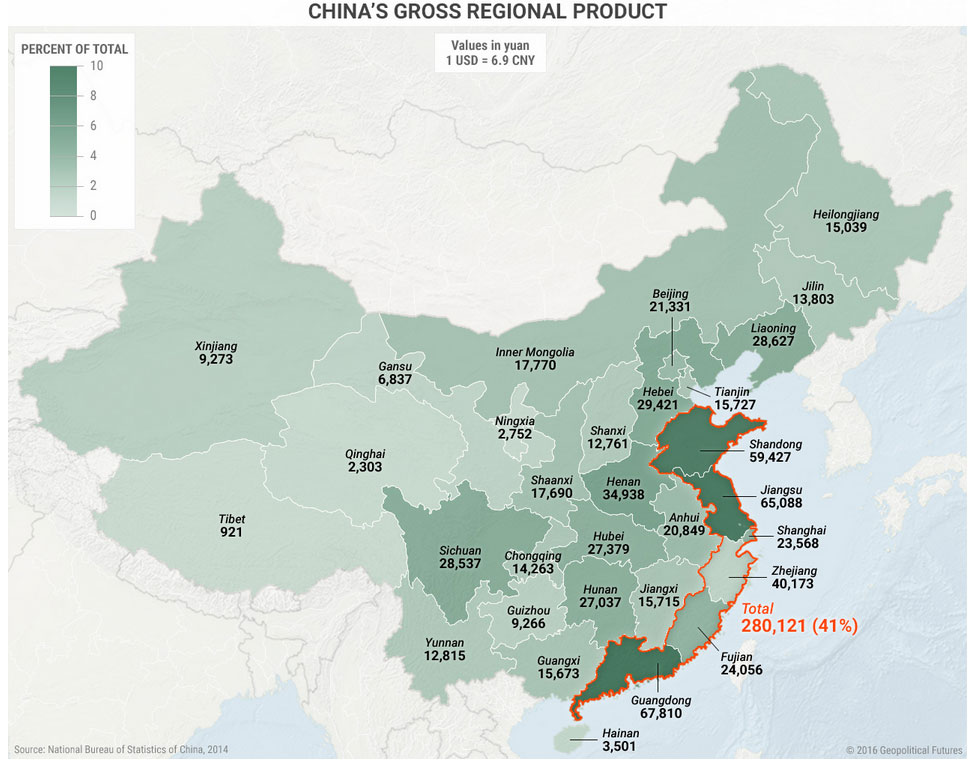

For China, that moment approaches again. The Deng era helped China to become wealthy, but the coastal provinces have benefited far more than the interior. For Chinese leaders, this is palatable during times of prosperity, but when economic growth slows, as it has recently, it creates a problem for the Communist Party, the legitimacy of which depends on keeping people wealthy enough – or at least well-enough fed – to not rebel against it. After all, the party came to power in a revolution of the people, not of the elite. Xi sees the risk and knows what’s at stake. So far, his approach in mitigating the risk has been to centralize power by taking it away from the provinces and suppressing political and social dissent.

Centralizing power, however, is just the first step in Xi’s plan to right the economy. The next step involves real measures to reduce economic inequality. (Xi’s government intends to eliminate rural poverty by 2020.) To that end, Beijing has directed infrastructure development to poor areas to help jumpstart growth. To encourage foreign capital inflows, China will create a more unified national investment environment. Instead of each foreign trade zone having its own “negative list” that determines which sectors foreign investors are allowed to participate in, Xi plans to make a national list, which would grant the central government more control over provincial and municipal economic managers, and allow it to incentivize investment outside of coastal provinces.

The goal is to get money into the interior. Over the past two years, Beijing has also placed restrictions on capital outflows from domestic sources to encourage investment in the nation’s inner provinces and discourage capital flight. Until now, coastal firms and wealthy investors have tended to put their money into foreign assets such as sports teams and hotels, which increased capital scarcity and forced the People’s Bank of China to sell foreign assets to stabilize the yuan. Investments in foreign countries now require approval to ensure they are either to gain technology in strategic industries or to fund One Belt, One Road projects.

Generally, it’s a mistake to overemphasize the importance of political speeches. But Xi’s was no ordinary speech. Over the past five years, he has instituted sweeping changes in a country resilient to change and has enhanced his power at the expense others. The people like him. Officials fear him. The military has been reorganized around him. And economic growth under him has declined slowly and steadily, not sharply or dramatically. In other words, his speech is notable, especially since it came during what is, by many accounts, the formalization of his power and policies.

About the Author

Matthew Massee is a writer for Geopolitical Futures.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.