Tunisia’s transition process remains one of the few bright spots of the Arab Spring. While the transitions initiated in Egypt, Libya and Yemen have experienced numerous setbacks and repeated outbursts of violence, if not outright civil war, Tunisia appears to be well on its way to securing a genuine democratic space for itself. This view is shared, for example, by the latest Freedom in the World Report, which ranks Tunisia as the first ‘free’ country in North Africa since Freedom House began its worldwide assessments of political rights and civil liberties in 1972.

Although there is a fast-growing body of research that attempts to explain Tunisia’s comparatively smooth democratic transition, the Western media has not been as upbeat. Most analysts have focused on the challenges Tunisia faces, including the instability being generated by neighboring Libya and the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. As a result, other important aspects of Tunisia’s external relations, particularly those that have had positive implications for its transition, have gone unnoticed.

Most importantly, Tunisia’s new political order appears to have benefitted substantially from the staunch support of those external actors who have the most leverage over the country. In contrast, those with a more critical attitude towards the transition have largely lacked the ability to influence the trajectory of the transition in less positive ways. These circumstances are far from accidental, by the way. They’re the consequence of the country’s history.

The centrality of France

Tunisia is the only Arab Spring country that has deep historical, economic and social ties with France. After occupying the country between 1881 and 1956, Paris has remained Tunis’ most important external partner in almost every domain ever since. In 2010, for instance, pre-Arab Spring trade with France accounted for almost 20 percent of Tunisia’s GDP. An estimated 1,200 French companies remain active in Tunisia and employ over 123,000 people. The two countries also share dense societal links, as exemplified by the roughly 660,000 Tunisians living in France, several thousand French citizens living in Tunisia, and the roughly one million French tourists that visit the country each year. To quote former French President Jacques Chirac: “France and Tunisia are two countries whose ties are such that whatever affects one affects the other immediately.”

Yet, this closeness seemingly blindsided the French when protests erupted in Tunisia in late 2010. The so-called Jasmine Revolution took the Sarkozy government by complete surprise and many saw Paris’ delayed response as an outrageous attempt to defy the aspirations of the Tunisian people. (Foreign Minister Alliot-Marie’s offer to provide the Ben Ali regime with the “savoir-faire” of the French security forces to contain the protests was particularly nettlesome.) There is little doubt that this public diplomacy debacle severely damaged the credibility and reputation of the French government in the eyes of those who soon came came to dominate Tunisia’s reconfigured political landscape.

However, bilateral relations improved significantly after François Hollande won the French presidential elections in May 2012. While the Sarkozy government had expressed little sympathy towards the Islamist-led coalition that the Tunisian people eventually voted into power, the socialist government under Hollande was more forthcoming and stepped up France’s support. As Figure 1 illustrates, France remained by far the most important bilateral provider of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Tunisia. Moreover, the two countries have also worked diligently to deepen security cooperation, especially after the Bardo attack [FR] in early 2015.

Given the above numbers, the support of Tunisia’s most important external partner should not be underestimated. Many recent African political transitions have faced far less goodwill from Paris, which has sometimes severely cut economic aid or, in the case of Mali, intervened militarily. While many politicians in Tunisia understandably hoped for more substantial support from Paris, at the end of the day it was highly beneficial for their country that France became a vocal economic and political supporter of the transition.

Steadfast support from the United States

Tunisia’s relationship with the United States has also benefited the country’s transition. Military cooperation between the two countries, which has its roots in the 1990s, remains strong. While economic relations are not nearly as extensive as with France, America has nevertheless been an important trading partner and investor in recent years. And perhaps most importantly, Washington’s response to the Jasmine Revolution wasn’t as sluggish as France’s. The Obama administration managed to limit its perceived complicity with the Ben Ali regime by openly criticizing the latter’s handling of the street protests happening at the time. It then supported Tunisia’s transition from the beginning, specifically by increasing its economic and military aid to the country (Figure 2). In addition to skyrocketing US arms sales to Tunisia (from less than USD 25 million in 2010 to more than USD 490 million in 2013), Washington also recently announced that it would triple its military and police aid to the country in 2015.

US diplomacy on the ground also played a very active role in the early stages of the unfolding transition. US diplomats engaged extensively with all major political forces in the country, meeting with politicians of all stripes as well as representatives of Tunisia’s influential civil society organizations. Rather than trying to abort Tunisia’s democratic experience, the Obama administration worked diligently to support the new political order and foster an atmosphere of political stability. It also promoted Tunisia’s transition on the international stage, presenting it as a successful and exemplary case of democratization, or – to quote John Kerry – “a beacon of hope, not only for the Tunisian people, but for the region and the World.”

Although there is room for more US support in Tunisia, it should not be forgotten that Washington’s support for a new political order in the MENA region is a recent phenomenon. For decades, the US and its European allies have both supported and tolerated dictatorships in this part of the world. Against this background, the continuous rapprochement between the US and Tunisia is a bold step forward, as illustrated by President Essebsi’s visit to Washington last May, when President Obama designated Tunisia a major non-NATO ally. (It’s a distinction that entails the same level of strategic cooperation as countries such as Japan and Israel.)

Ambivalent relations with the Gulf monarchies

Another noteworthy aspect of Tunisia’s transition process has been the relatively minor role played by regional powers such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). While these monarchies have played a more active spoiler and promoter role in other transitioning states, they lack the local allies they need to steer Tunisia’s transition in the directions they want.

In stark contrast to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Qatar voiced strong support for Tunisia’s transition. After the Jasmine Revolution, Doha wasted no time positioning itself as a ‘strategic partner’of the ‘new Tunisia’ – an announcement that was also accompanied by generous economic support. Qatar’s rising profile in the country soon sparked suspicion, however. After Doha was repeatedly accused of bankrolling the moderately Islamist Ennahda Movement, large segments of the Tunisian public grew hostile towards the Emirate, as illustrated by regular anti-Qatar protests, social media campaigns and Al Jazeera’s fast-declining audience share in the country. Since the dissolution of the Ennahda-led Troika coalition in late 2013, relations with Qatar have cooled down noticeably, and little of consequence has transpired between the two countries. On balance, this suggests that that Doha has ultimately been less crucial for Tunis than Paris and Washington have been.

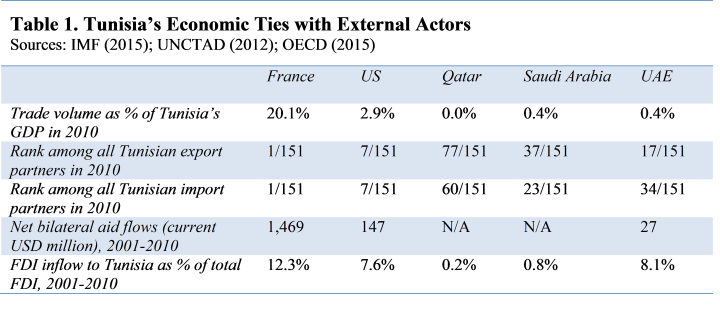

The ambivalent nature of Tunisia’s relations with the Gulf monarchies is obviously rooted in history. Tunisia has typically been Europe and Western-oriented, while the highly conservative and insular Arabian Peninsula has typically focused on issues ‘closer to home’. As a result, Tunisia’s interactions with the Gulf monarchies continue to be modest. Tunis, for example, has more extensive trade relations with Switzerland than with the Gulf’s foremost economic power, Saudi Arabia, while the country’s diaspora within the region is only a fraction of that in Europe. In terms of economic assistance and foreign direct investment, the Gulf monarchies have also mostly played a minor role in the country, as illustrated in Table 1. This light footprint, as to be expected, has translated to weaker leverage in Tunisia than in countries such as

Egypt and Yemen.

The future’s bright

It would be simplistic to claim that Tunisia’s political trajectory has been solely (or even primarily) shaped by its external relations. But to ignore the international dimension is to miss an important piece of the puzzle. External factors have clearly facilitated Tunisia’s transformation from a heavy-handed dictatorship into a messy but working democracy in less than four years. Moreover, not only was Tunisia relatively detached from the ‘leaders of the counterrevolution’ in the Gulf, it received substantial pro-revolution support from its traditional partners. Compared to the other Arab Spring countries, therefore, Tunisia’s experience clearly stands out. No other Arab Spring country had such close historical, economic and societal ties to Europe and the West. Indeed, Egypt’s and Yemen’s far closer ties with the Gulf region merely complicated the already difficult task of moving their transitions forward. Although Tunisia still faces many challenges, ranging from socio-economic ones to growing security concerns and regional instability, there is reason for cautious optimism that its transition process is unlikely to be derailed from abroad.

Andreas Kaufmann is a Student Editor at the International Relations and Security Network (ISN) at ETH Zurich. This blog is a summary of his Master’s thesis recently submitted to the University of Zurich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.