Water has become a hot button issue on the international stage. The fear of water scarcity and its implications for human security has been acknowledged by leaders and decision makers across the globe. For example, the United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon has warned that “the consequences for humanity are grave. Water scarcity threatens economic and social gains and is a potent fuel for wars and conflict.” Yet, the challenges posed by water scarcity are a manifestation of the lack of management of resources rather than an actual physical shortage. So while conflict over water resources is possible in many parts of the world, the threat is not due to scarcity but mismanagement. This begs a question – can water bodies ever be jointly managed for equal benefit? We at the Strategic Foresight Group (SFG) believe so.

The Good News

According to the findings of our new report “Water Cooperation for a Secure World”, any two countries that are engaged in active water cooperation do not go to war. We are also convinced that if countries cooperate to ensure water supplies they are also far less likely to come to blows over ideologies, economic competition and other factors. Indeed, cooperation between states over water resources not only reduces the chances of war, but also enhances the prospect for social and economic development in other areas.

There are several examples of countries that have achieved this level of cooperation and enjoyed the surplus benefits. In 1966, Argentina initiated co-operation between its neighbors with the creation of the Intergovernmental Coordinating Committee of the La Plata Basin Countries (CIC). Joint management of the world’s fifth largest basin – as well as the Parana, Paraguay and Uruguay Rivers – has not only safeguarded the region’s biodiversity and natural resources, but has also helped to boost the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the five member states.

Elsewhere, South Africa has provided economic assistance to Lesotho in return for access to its abundant water resources. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project is essentially based on the development of dams that provide Lesotho with sustained levels of hydropower. It also safeguards South Africa’s access to shared waterways.

Since 1963, the countries of the Senegal River Basin have been working under the auspices of the Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur du Fleuve Sénégal [FR] (OMVS) to overcome challenges related to agriculture and drinking water supply. Cooperation has not been without its fair share of success stories. Prior to joining the OMVS Senegal’s agricultural output was severely affected by droughts and flooding. However, the joint construction of the Manantali dam with OMVS partners has helped to increase irrigation over the last three decades. It is also estimated that 90 per cent of Senegal’s rice crop is harvested in the region. In addition, the construction of a dam that stems the flow of saltwater has also pushed Senegal ever closer to achieving its Millennium Development Goal targets on drinking water supplies.

And the Bad…

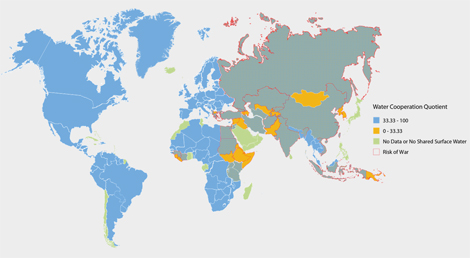

Unfortunately, our report also finds that out of the 148 countries covered, 37 do not engage in any significant cooperation with neighbouring countries over water supplies. These include fragile and war torn states like Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Somalia, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Our findings – be they positive or negative – are based upon the formulation of a Water Cooperation Quotient. This measures on a scale of 0 to 100 the actual extent of cooperation between riparian countries and is based on 10 key parameters. These include environmental cooperation, economic development, political dialogue and more. Plotting this quotient on a map that demarcates countries facing risk of war merely confirms that states with a high Water Cooperation Quotient do not go to war.

This bodes well for the future of unresolved water issues around the world, particularly in regions which are located towards the lower end of the Water Cooperation Quotient. For example in the case of India and Bangladesh cooperation over the Teesta river basin can be mutually beneficial to both countries. India allowing enough water to flow to Bangladesh would help farmers there during the dry period and also help ecosystem preservation. Bangladesh could help India on critical security issues in return. That way, both countries would get what they most critically need for survival and security.

Accordingly, cooperation over shared water resources undoubtedly offers another gilt-edged opportunity to strengthen relations between countries and bring greater stability and peace to trouble-hit regions.

Priyanka Bhide is a Communications Officer with the Strategic Foresight Group. She is responsible for the SFG’s overall communication strategy including its various outreach activities and media relations.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Mediating Water Use Conflicts in Peace Processes

Blue Peace in the Middle East

Trends and Triggers: Climate Change and Interstate Conflict

International Coordination of Water Sector Initiatives in Central Asia

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.