This article was originally published by The Conversation on 10 October 2014.

In the last few years, the list of sensitive government information made public as a result of unauthorised disclosures has increased exponentially. But who really benefits from these leaks?

While they are media catnip and provide useful information to hostile individuals and organisations, they only occasionally contribute to the public debate on intelligence and truly advance the cause of democracy.

A scoop on the secret world of espionage is a guaranteed journalistic coup. And with good reason; at the simplest level, news exposures of intelligence service activities inform the public and contribute to a self-evidently important public debate on the role of intelligence in modern democracies.

The leaks orchestrated by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden have triggered a broad international debate on the means and extent of surveillance used by Western countries – particularly the US and UK – the likes of which we have rarely seen before. Snowden has not just exposed widespread surveillance programs, he has also substantially eroded public confidence in the trustworthiness of Western governments and their national security establishments.

Despite the efforts of some top intelligence officials who in the late 2000s proposed a new social contract between the government and the people on intelligence matters, it took Snowden’s revelations to start a full-blown debate on the issue, one that has drawn in political leaders, intelligence officials and the wider public.

But on another level, the Snowden affair shows how broken our relationship with intelligence agencies has become; it should not take a scandalous data dump to prompt renewed democratic control and oversight of intelligence.

It seems that instead of having a constant reflective debate over what kind of national security establishment we want, we have fallen into a leak-dependent complacency, a system of “regulation by revelation”. And that carries severe risks in itself.

Caution to the Wind

Despite what some commentators and campaigners have argued, information leaks clearly do not always serve the public good, nor do they necessarily help to undercut embedded power structures. Instead, they are just as easily used for purely political purposes by senior officials to weaken opponents, or to discredit policies deemed to be erroneous – purposes that have nothing to do with public oversight of state power.

We don’t have to look far for examples. Think of July 2003, when a leak from a State Department official led the Washington Post to publish the name of CIA officer Valerie Plame, effectively ending her covert career and putting her life at risk. This was widely considered a retaliation for Plame’s husband Joseph C. Wilson’s open criticism of the Bush administration’s case for war in Iraq.

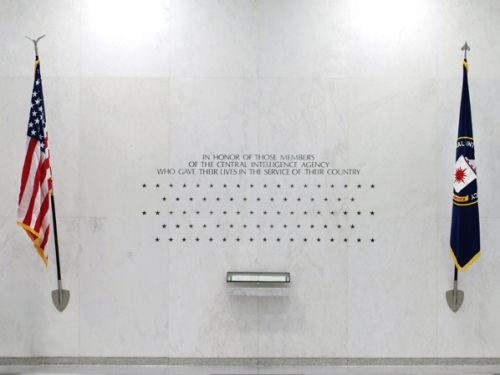

Leaks have also long been used by intelligence officers themselves to harm their own intelligence agencies, while doing little for democracy. In the 1970s, Philip Agee, a former CIA employee, expressed his disillusionment with the CIA and launched a smear campaign against it, revealing the names of CIA officers, agents and front companies. By doing so, Agee put his former colleagues’ life in danger and hardly improved the relationship between the agency and the public.

Some of the leaks orchestrated by Snowden similarly appear likely to have done more harm than good. The publication by Cryptome of an unsanitised version of a congressional budget justification of the US intelligence community, including a list of the main targets of US counterintelligence, has certainly offered valuable information to hostile agencies in Russia, China, or North Korea, but it has done little to advance the public debate on the role of intelligence in US democracy.

On top of that, there’s the credibility problem. The mega-leaks of information have thrown the ability of the US intelligence community to protect sensitive information and the identity of its sources into doubt, casting a major pall over its agencies’ work. According to former intelligence officer David Gioe, the discredit brought about by the leaks will severely damage US intelligence collection capabilities over the long term.

Ultimately, the jury is still out on whether the recent disclosure of details on the activities of American intelligence in the field of counter-terrorism were really necessary for the purposes of public information.

While Snowden’s dust is still settling, the mainstream media must think hard about why and how it should cover intelligence affairs. A public debate driven by leaks, scandals and data dumps is guaranteed to be harmful; it will antagonise governments and intelligence agencies, and is likely to generate ever-stronger and more irreconcilable opinions rather than a reasoned consensus on civil liberties.

Stemming the Flow

Make no mistake: a debate on the role of intelligence in a democracy is necessary and valuable, and in the 21st century, more so than ever. But to serve a noble purpose, it must be focused on the substantive issues and procedures, and the core ethical issues at play. To meet that threshold, we don’t need to know the exhaustive budget lines of the consolidated cryptologic program, or the number of intelligence officers speaking French and Chinese (as set out in the US “black budget”).

For years, common sense dictated that knowing a broad outline of what the government does is sufficient in most cases – and that the details should be discussed behind closed doors by specialised institutions within the apparatus of the state. This state of affairs has clearly become unacceptable to many citizens, who feel they need to know more.

That need be no bad thing; an electorate interested in intelligence affairs can raise the stakes for governments and provide a much-needed incentive for representatives to hold intelligence agencies to account.

But endless indiscriminate unauthorised disclosures and their publication by the media can poison the public debate as much as they can nurture it. Until the intelligence establishment accepts to adapt and becomes more transparent – and until the media figures out clearer norms of what constitutes reasonable disclosure, intelligence will still be subjected to a highly imperfect debate.

Damien Van Puyvelde is Assistant Professor of Security Studies and Associate Director for Research at the National Security Studies Institute (NSSI), at the University of Texas at El Paso.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.